Approximately $18B (£11B) are spent annually on humanitarian aid by more than 140,000 staff. U.N. appeals solicit life-saving help for 52 million people across 19 countries. Yet the entire system is under unprecedented strain.

Civil strife means that whole populations are caught up in conflict. In Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Syria and Zimbabwe, an average of 75% of the entire populations have been directly affected. Worldwide, more than 172 million people were touched by conflict in 2012. Last year, there were 35 million people displaced – 10.5 million across borders, and double that number within countries.

These trends have profound implications for humanitarian action. First, while huge numbers of people in Asia and Africa continue to rise out of poverty, those who remain are increasingly in fragile states, exposed to war and crisis. In 2005, just 20% of the global poor were in conflict-affected and fragile states. Today, that figure is 50% and set to rise to more than 80% in 2025.

For many years, people have questioned the conventional distinction between the humanitarian system that responds to emergencies caused by wars and natural disasters, and the development community that, in the longer term, seeks to tackle poverty. When the majority of the global poor live in fragile states, and when the average refugee spends nearly 20 years outside his home country, the distinction has, in reality, dissolved – yet it still conditions many of the institutions that govern this work.

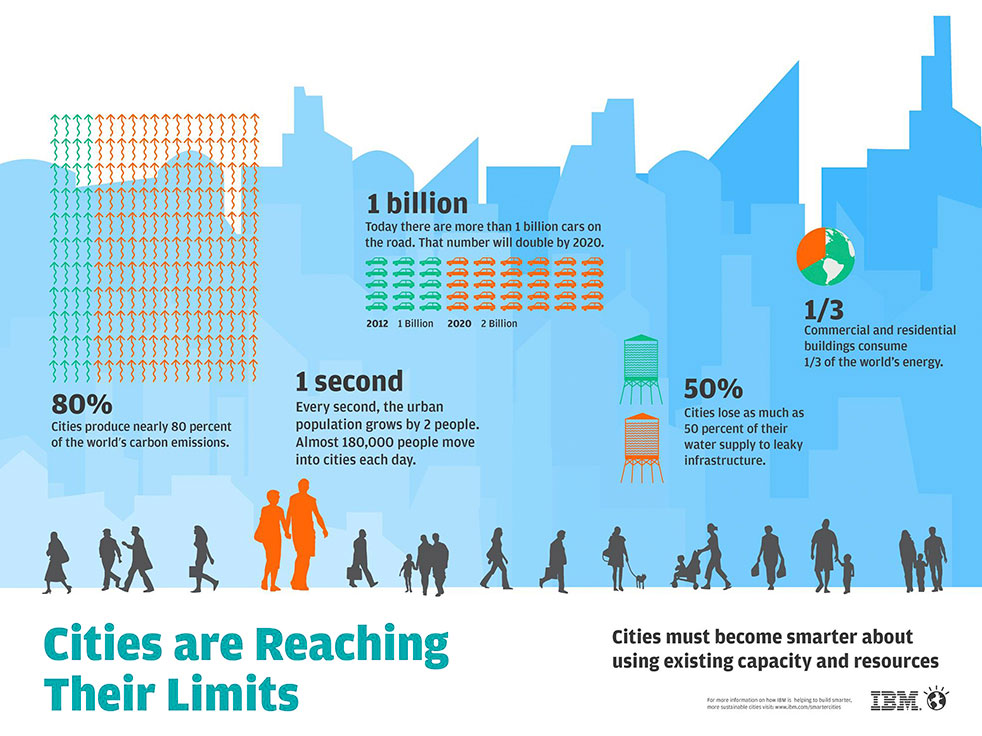

Second, we need to think hard about the modern needs of those displaced by conflict. The face of the refugee is no longer only someone living in a tent in a vast camp – it is increasingly that of a family squatting in an abandoned building in an urban area, or crammed into a one-room apartment on the outskirts of a small town, with nowhere to send their kids to school. With the urban populations of Africa and Asia set to double or even triple in coming decades, their services and systems will come under ever more stress.

We need to think about the universal services, infrastructure and local economies used by both host communities and those displaced by conflict, as well as targeted services for refugees. That means, among other things, working with and through local partners and governments, not bypassing them.

Third, the demands on the humanitarian system are set to grow not just in scale and duration, but in complexity. This is not just from the civil wars in the Middle East, Africa and South Asia. Population surge, concentrated in cities, combined with the droughts, water shortages and natural disasters that are the consequences of climate change, will increasingly affect the most fragile areas of the world.

With new players coming into the humanitarian system, notably from Muslim-majority countries, there is pressing need for common purpose. The millennium development goals (MDGs), despite some shortcomings, brought focus, attention and resources to development efforts. We need a similar coalition for change in response to humanitarian crisis. Do we need humanitarian goals?

The classic definition of humanitarian action is simple: we exist to save lives. But, in fact, we have other priorities too. Protecting women and girls from violence, investing in disaster risk reduction, promoting economic livelihoods are part of the humanitarian enterprise.

Humanitarian goals (HuGos) could take several forms. They could be distinct from the successor to the MDGs post-2015, or integrated within them. They could rationalise existing – and overlapping – humanitarian norms and technical standards (so-called Sphere standards that, for example, specify the minimum amount of water a person should receive per day), and give them teeth through global commitment and monitoring. They could raise the bar of quality for the entire humanitarian system through global quality standards. More challenging, given the diverse contexts, they could define outcomes, such as response times, literacy rates or child mortality.

With the MDG revision process under way, and a humanitarian summit announced for 2016, now is the time to debate what purpose humanitarian goals could serve, and what they should be. At the moment, we are playing catch up. It is time to get ahead of the curve.