Some 140 million students have not returned to class this year. This is according to UNICEF, which also provides another particularly sad and alarming figure: at least eight million children had to wait for the first day of school for one year or more as their schools were closed for the duration of the coronavirus pandemic.

The result is a dramatic step backward from the many advances painstakingly achieved in recent decades, especially in terms of access to education. But it is also a serious mortgage on the future of so many countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where more than half of all children are not enrolled in schools, in regions scarred by crisis and conflict where the right to education is often not guaranteed, or where there are still major gender disparities.

These are all situations that the coronavirus pandemic has only exacerbated as documented in the report produced by UNESCO, UNICEF, the World Bank, and OECD and presented in July 2021, Survey on National Education Responses to COVID-19 School Closures.

The survey, conducted in 142 countries, illustrates a particularly bleak picture: one in three countries has not implemented recovery programs after school closures due to the coronavirus; one in three (i.e., only high-income countries) is beginning to assess losses in primary and secondary education levels; less than one in three (i.e., low-and middle-income countries) has been able to ensure early return to attendance.

Consequences

The consequences have been not only severe learning deficits, but also a significant increase in school dropouts and related phenomena such as forced marriages, child labor, street children, and even malnutrition. For many students, the closure of schools has also meant deprivation of their only meal a day: during 2020, the number of malnourished children increased by about 80 million mainly due to lack of access to school.

After all, as the report highlights well, schools were completely closed in all four levels of education for an average of 79 days, or about 40 percent of the total OECD and G20 average. But in the poorest countries, it was as high as 115 days of closure.

And it’s not over yet: nations like Uganda or South Africa, which have faced a particularly severe wave of coronavirus in the past few months, have closed schools again and applied lockdown measures with serious repercussions in all spheres of economic and social life as well.

In addition, many countries in sub-Saharan Africa (and beyond) have failed to deploy alternative modes of teaching, online or through television. “Remote learning, pointed out Robert Jenkins, UNICEF’s education officer, has been a lifeline for many children around the world during school closures. But for the most vulnerable, it has been impossible.”

The Case Of Guinea-Bissau

In Guinea-Bissau, for example, COVID-19 has taken a toll on a school system already in a comatose state due to non-payment of teachers’ salaries and the resulting continuous strikes. “For about three years now, schools have been running hiccup-like,” recounts Father Naresh Gosala from the PIME mission in Catió, a southeastern region of the country, “and during the first months of the pandemic they were closed altogether.”

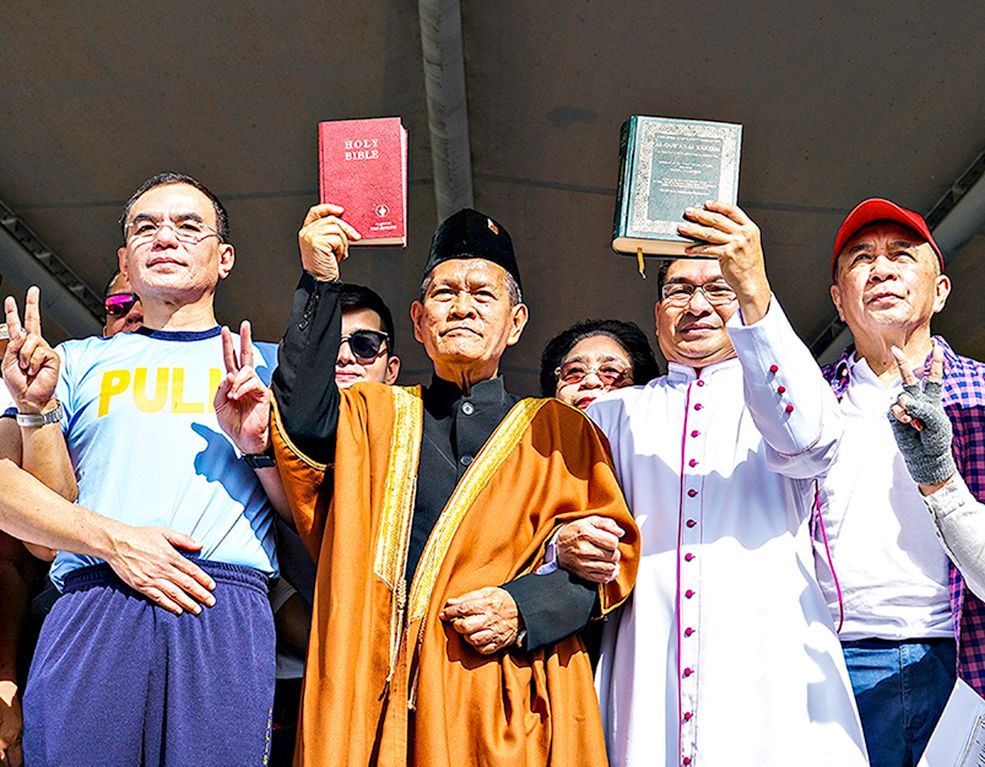

“Thanks to contributions, we have been able to provide teachers with a minimum salary, so we have been able to keep them open almost all the time. In addition, we provided masks and disinfectant gels and complied with all anti-COVID regulations. The same goes for the school of the Benedictine Sisters in Catió as well as the Catholic high school in Bafatá or the schools of the Missionaries of the Immaculate Conception in various parts of the country as well as in the school that PIME used to run in Bissau.”

In a country as poor as Guinea-Bissau, all this means further clipping the wings of thousands of young people who, without an education, will have little chance of improving their living conditions. Moreover, here as elsewhere, no distance education initiative has been put in place.

Even catch-up programs have been implemented only in countries with more resources, and in some cases increased education budgets, but are extremely small if not nonexistent in many disadvantaged settings. “Reopening at best,” Jenkins argues, “means implementing such programs to help students catch up and ensuring that priority is given to vulnerable girls and children.”

Girls At Risk

Female students, who had made great strides, especially in elementary school, are again at risk of being excluded from educational systems. Not only that, many of them, due to school closures, were immediately placed in informal labor networks to help families in severe economic hardship due to lockdowns; others were forced into early and forced marriages, a way for the family to “get rid” of a mouth to feed and get the dowry.

According to another UNICEF report, COVID-19, A Threat to Progress Against Child Marriage, by 2030 there could be ten million more child brides, threatening years of progress in reducing the phenomenon: “School closures, economic stress, disruption of services, pregnancies, and parental deaths due to the pandemic expose the most vulnerable girls to the risk of early marriage to a greater extent.”

According to research data, there are about 650 million women and girls worldwide who were married off as children; about half are in Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, and Nigeria.

Street Children

In India, as in many other countries, the pandemic and related economic and school access difficulties have pushed many boys (but also quite a few girls) into street life, where the number of street children has grown significantly.

According to the Consortium for Street Children, “many lack access to clean water, health care, and shelter. On the streets, they can contract the virus and, due to poor health conditions, are at greater risk of developing complications. Street children face discrimination and cruelty from communities that fear the virus and those who should protect them: police and other authorities. They need health services, but they also need the information to help them understand how to protect themselves.”

“The situation in, Yaoundé, has been really problematic,” confirms Father Maurizio Bezzi, a PIME missionary who has been working with street children in Cameroon’s capital city for 30 years. “Street children are particularly at risk because the pandemic is adding to conditions of extreme poverty and precariousness.”

Last year, the government imposed the closure of not only schools but also shelters such as the Edimar Center created by Father Bezzi. “When the measures to contain the coronavirus were announced,” explains current manager Mireille Yoga, “we immediately took steps to raise awareness among the street children so that they would understand the gravity and urgency of what was happening in a country where there are not even facilities capable of taking care of the sick. And so the workers, instead of welcoming the boys in the Center (about a hundred a day), went to the streets themselves to follow up with the youngest, give them some advice to protect themselves and a minimum of assistance.”

Also in Bangladesh, distance education has also been a failure even in the universities that have used it: only ten percent of students have been able to take classes online because most cannot afford a computer or Internet connection. “The figure reflects the distributions of wealth in Bangladesh,” says Alberto Malinverno, a volunteer of the Association of Lay PIME, “the better-off are a very small segment of the population, so it is normal that only they were able to take online classes.”

Cambodia

The country has recorded far fewer cases of COVID-19 than other Southeast Asian nations, but despite the small number of deaths, schools have been closed for nearly two years and are being used as quarantine sites.

To limit the number of drop-outs, Father Alberto Caccaro, a PIME missionary, and Cambodian teachers have come up with an alternative solution: groups of 10-12 pupils meet at one of the boys’ homes or in a classroom at the PIME schools while teachers shuttle from one group to another and give shorter lessons. This at least provides some continuity in educational activities.

“The children do not lose their sociability and do not isolate themselves, although in the countryside the risk of this happening is less than in the city,” Fr. Caccaro says. “Moreover, since we are dealing with small groups of students, contagions can be kept under control more easily. PIME will soon open another institute in Cambodia,” Fr. Caccaro joyfully announces, “It is our way of reacting to this situation and not betraying the trust of the children.”

But it is also one of the many efforts being made around the world so that we really focus on education as a fundamental way to build a more fraternal world. Reprinted with permission of Mondo e Missione