On June 3, 1963, Pentecost Day, the long agony of Pope John XXIII, the Pope of Vatican II, came to an end at 19.45 hours. Ten days earlier, on Ascension Day, he spoke to the pilgrims in Saint Peter’s Square for the last time, as if sensing his impending death: “With our desire, we run after the Lord who goes up to heaven…” Immediately, the public appearances were suspended; the pope was ill. The whole world followed the pope’s terminal illness with trepidation. The end was approaching, but his mind remained lucid to the last minute.

As ironic as it may seem, Pope John’s death marked the climax of his pontificate and amplified the Church’s consensus for a pope who had put in motion a phenomenon of unusual proportions – the Second Vatican Council. His death, it seemed, was experienced by the whole of humanity. It was a final witness to poverty, consistent with a lifestyle pursued with utter commitment. Many years before, in his last will, he wrote: “Born poor, but from honorable and humble people, I am particularly happy to die poor. I thank God for this grace of poverty that I vowed in my youth, spiritual poverty as a priest of the Sacred Heart, and real poverty…In the hour of saying farewell, or better, good-bye, I remind all of what is dearest in life: the Blessed Jesus and His Church; the Gospel of the ‘Our Father’; truth and goodness – benevolent, resourceful, patient, undefeated and victorious goodness.”

A HISTORICAL CHOICE

A trait of great significance in Pope John XXIII was the kind of peaceful strength with which he always expressed his convictions. During his reign as pope, this strength became evident in all its disconcerting splendor. It was with this same certainty, only ninety days after his election on January 25 1959, that Pope John XXIII announced his intention to convoke an ecumenical council. He made the announcement to the cardinals gathered in the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls on the concluding day of the Week of Prayers for Christian Unity. He repeatedly stated that he wanted a new Pentecost to once again bring the gifts of the Holy Spirit on the Church, renew her youth, and respond to the “signs of the times,” opening her anew to her universal mission.

The Second Vatican Council has defined the history of the modern Church. It took place between 1962 and 1965. Blessed John’s successor, Pope Paul VI, had the task of bringing the Council to its conclusion. The discussion among the Council Fathers was intense and articulate; the arguments vivacious, under the unusual attention of the world media. The resulting Council documents are solid contributions to the Church’s doctrine and tradition. The entire Church turned a glance of empathy towards the “joys and sorrows” of humanity, becoming conscious of including herself more in the world.

A renewed vision of the Church as the “pilgrim people of God,” brought to the fore the colorful reality of the local Churches already present all over the world, as the fruit of the gigantic missionary wave of the 19th and the first part of the 20th century. The liturgical reform enhanced the self-consciousness of the different local communities, empowered also by the renewed interest and appreciation of the Bible, God’s Word. But three smaller documents, that initially appeared to be a historical choice to overcome the impasse of centuries and opened the horizon of the future, turned out to be the catalysts for change.

With the decree Unitatis Redintegratio (The Restoration of Unity), the Catholic Church now looked at the other Christian Churches as bearers of the same faith and committed herself to the ecumenical cause. With the declaration Dignitatis Humanae (The Dignity of the Human Person), the Church embraced the principle of freedom and, in this way, entered defenseless into the world arena, relying only on the power of God and in the self-evident goodness of the Gospel message. Meanwhile, with Nostra Aetate (In This Age of Ours), the heartwarming conviction of God’s universal salvific will enabled the Church to look at non-Christian religions as genuine vehicles for “the seeds of the Spirit” and to enter decidedly into the way of tolerance and dialogue.

Fifty years later, these positions are still vital to how the Church conducts itself in the world. They were embraced and carried forward by the forceful witness of Pope John Paul II in his exceptionally long pontificate, then by Pope Benedict XVI, and now, by Pope Francis.

EVE AND THE APPLE

Pope John XXIII was born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli at Sotto il Monte, a village near Bergamo in Northern Italy, on November 25, 1881. The son of a patriarchal family of farmers, he was marked, since his childhood, by a good, down-to-earth sense of realism, and a profound, uncomplicated Christian faith. At a very young age, he entered the seminary, and was ordained a priest at 23. He progressed rapidly in his ecclesiastical career: first as the bishop’s secretary, then as part of the dicastery Propaganda Fide in Rome.

Just before his priestly ordination, he had experienced military life because of the compulsory military service required by the state. He again went back to the Army as a priest during World War I, from 1915 to 1918, serving at the frontline as a stretcher-bearer. In 1925, he was made a bishop and sent to Bulgaria as Apostolic Delegate. He spent ten years in close contact with Orthodox Christians and another ten years in Istanbul, Turkey in the same capacity, this time dealing with the Muslim brethren.

It was there that he weathered the World War II years. In 1944, he was sent by Pope Pius XII to France as his nuncio. In all, he served 28 years in the Vatican Diplomatic Service, which shaped his personality. It was from this experience that he acquired his openness towards cultural worlds different from his own and honed his tolerant and humane approach to people.

In Paris, during a state dinner at which he took part in an official capacity, a lady with a plunging neckline happened to be seated not far from him. In the course of the meal and the conversation, Msgr. Roncalli kindly offered an apple from the fruit bowl to the lady. To the puzzled look of the person seated near him, the nuncio whispered: “It was biting the apple that Eve realized that she was naked.”

In 1953, he was made a cardinal and sent to Venice as Patriarch. From there, God chose him to succeed the prestigious figure of Pius XII on October 28, 1958. From then on, the adventure of the Second Vatican Council began.

“IL PAPA BUONO”

Pope John’s death was “his greatest homily,” his most profound statement on the theme of Christian faith as a public virtue. For centuries, what mattered most about outstanding servants of the Church was almost exclusively their private virtue. At first glance, Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli appeared as a common, ordinary Christian. Yet from him emanates a rare consciousness of the simplicity of confessing the Gospel to everybody, without arrogance or omission. His search for meekness became more acute, as if to balance his position of authority. He grew even more daring with the growing of his pastoral responsibility.

Pope John’s life is marked by the unbreakable unity between his religious personality and his service as pope. His spirituality appeared to be “common,” inasmuch as it reflected the condition common to all Christians. This is evidenced by the name which people liked to call him: Il papa buono (the “Good” Pope). Within the Church, “good” is one of the most common adjectives. However, it has the most profound meaning. With his canonization, John XXIII will officially enter the company of the saints, emphasizing that same virtue which happens to be the Church’s real strength.

THE POPE FROM THE EAST

The crux of the life and legacy of John Paul II is his Polish nationality: after more than 400 years of popes of Italian origin, he was the first non-Italian, a man from East Europe, and from the communist sphere of influence for that matter. Since the beginning, Pope John Paul II considered communism as a passing cloud. For him, the real issue at stake was the unity of Western and Eastern Europe. He defined West and East as the two lungs that enable Europe to breathe. Once the united Europe became a reality, he proceeded to revive the richness of the Christian roots of Europe.

Pope John Paul II was born Karol Józef Wojtyla on May 18, 1920 in Wadowice, Poland. His early life was marked by great losses. His mother died when he was 9 years old, and his older brother, Edmund, died when he was 12. Growing up, John Paul was athletic and enjoyed skiing and swimming. He went to Krakow University in 1938 where he showed an interest in theater and poetry. The school was closed the next year by Nazi troops during the German occupation of Poland.

Wanting to become a priest, John Paul began studying at a secret seminary run by the Archbishop of Krakow. After World War II ended, he finished his religious studies at a Krakow seminary and was ordained in 1946. John Paul spent two years in Rome where he finished his doctorate in theology. He returned to his native Poland in 1948 and served in several parishes in and around Krakow.

John Paul became the Titular Bishop of Ombi in 1958 and then the Archbishop of Krakow six years later. Considered among the Catholic Church’s leading thinkers, he participated in the Second Vatican Council. As a member of the Council, John Paul helped the Church to examine its position in the world. Well regarded for his contributions to the Church, John Paul was made a cardinal in 1967 by Pope Paul VI.

In 1978, John Paul was elected to the Chair of Peter, succeeding the brief and tragic pontificate of John Paul I. As the leader of the Catholic Church, he traveled the world, visiting more than 100 countries to spread his message of faith and peace. But it was in Rome where he faced the greatest threat to his life. In 1981, an assassin shot John Paul twice in St. Peter’s Square. By a special grace that he attributed to the Blessed Virgin Mary, he was able to recover from his injuries and later forgave his attacker.

MILESTONES OF A PONTIFICATE

The great drama of the fall of Communism revealed the remarkable hidden history of John Paul II as one of the dominant figures of the twentieth century. He became the inspiration and the protector of Solidarity, a workers’ movement in the heart of the Communist world, and contributed to keeping Solidarity alive underground, after Moscow seemed to succeed in crushing it.

To what extent the Polish pope contributed in bringing about the collapse of the Soviet empire with hardly a shot fired – contrary to the predictions of all observers – will be left for historians to debate about. Yet “everything that happened in Eastern Europe would have been impossible without the presence of this pope,” wrote Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. “How many divisions has the pope?” Stalin once asked contemptuously. Yet in the end, it was Pope John Paul II who held the key to destroying the Soviet empire.

From the beginning of his pontificate in 1978, Pope John Paul understood that his commission from the Lord was to lead the Church into the new millennium. It is said that the Polish primate, Cardinal Wyszinski, told John Paul II immediately after his election that this would be his task. In his first encyclical letter, Redemptor Hominis (The Redeemer of Man) in the spring of 1979, John Paul II asked: “What should we do, in order that this new advent of the Church, the end of the second millennium, may bring us closer to God, the “Everlasting Father”? He wrote then that only one answer was possible: ‘Our spirit is set in one direction: towards Christ, the Redeemer of man.” John Paul was consistent with this teaching. In fact, this was the core of the message of his great document Novo Millennio Ineunte (At the Beginning of a New Millennium), written in order to lead the Church into the future: “starting afresh from Christ.”

MARTYRDOM AND HEALING OF MEMORIES

At the beginning of the Great Jubilee Year 2000, John Paul II proposed the theme of martyrdom and referred to the 20th century as the century of martyrs: people killed not only in the name of Christ but because of defending human dignity, in the name of charity, justice and solidarity. Pope John Paul proclaimed scores of martyrs as saints. Martyrdom, therefore, was not a thing of the past, but a wealth of the present for the Christian community that embraces all the Churches.

Martyrdom, that is the spilling of the blood of different Christians during one of the most violent eras in the history of humanity, became the basic, yet most profound, lesson in ecumenism that the world ever had. John Paul II wrote in Ut Unum Sint (So That They May Be One): “The courageous witness of so many martyrs of our times who belong to the different Christian denominations constitute, as it were, the vanguard of the ecumenical movement. From the places of their martyrdom, they exhort the Christians to speed up the journey towards unity. We can say that they are the prophets of unity: their blood seals the Lord’s appeal for unity. Their blood is not only semen Christianorum (the seed of new Christians), but also semen unitatis (the seed of unity).”

One of the signs of the Great Jubilee Year that captured the imagination of the international media and of non-Catholics was the purification of memories: John Paul II asking forgiveness for the sins and mistakes that the Church committed throughout the past millennia and especially during the last century. For this purpose, he inserted a written prayer of forgiveness into one of the cracks of the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, during his pilgrimage there. He pronounced a prayer of forgiveness in the synagogue of Yad Vashem, the place dedicated to the memory of the Holocaust on the same occasion. These were not improvised gestures but the mature fruit of the spirit of Vatican II. It was one of the most interesting events of his entire pontificate which had a prophetic value: the purification of the historical memory opens wide the Church to the future.

WORLD YOUTH DAY

John Paul opened the Church even wider, by reaching out to those in the Church who seemed to have been neglected in years past – the youth. Theirs was an atypical relationship – a friendship between an aged witness of the faith and the youth of the whole world. While many saw the youth as being escapist and bereft of passion, John Paul II saw in them inner strength, dreams, and untapped energies. Gently, with a language that was at the same time plain and powerful, he invited them to be the protagonists of the future.

For their part, the youth perceived him as a trustworthy friend; they saw him as a man who was not backward-looking. He was the image of a complete man who had known what life is as a university student, a factory worker, a writer, an actor, a priest, a bishop and a pope. John Paul’s message to the youth was of extreme clarity. He was able to challenge them because he himself had experienced the uncompromising demands that society placed on them.

More than thirty years ago, John Paul II had the great intuition of calling the World Youth Day gatherings in order to entrust a definite mission to them both in the Church and in the world. For him, they were the future, they are those who will enact the civilization of love that will oppose the “culture of death” he often denounced.

And so, every two years, thousands have streamed together to the most distant and diverse parts of the world. Czestochowa, Santiago de Compostela, Denver, Toronto, Manila, etc. are places already immortalized for the extraordinary encounters that were experienced and the challenges given to the youth by an unlikely idol. Some have happily contrasted this extraordinary concurrence of thousands of youth to the gatherings of young soldiers who, only seventy years ago, upheld the symbols of destruction and death of Nazism. The success of the World Youth Day continues even after John Paul’s death, in the pontificates of Benedict XVI and Pope Francis.

The youth did not pity John Paul II even when he became old and sick. It became a sobering experience for many to see how a person so debilitated by sickness could still have a strong moral authority. John Paul II gave the impression of being younger than the youth themselves. He was recognized as one of the very few significant figures in the world who was capable of capturing the imagination of the young. And this was very important for the young who needed solid points of reference or a guide who gave instructions with certainty.

“WAR NEVER AGAIN!”

Perhaps Pope John Paul’s most remarkable milestone was his commitment to peace. Amid the threat of violence triggered by the black cloud of terrorism looming at the horizon of humanity, John Paul II embraced the cause of peace with stubborn determination. The absolute condemnation of war on the part of Pope John Paul, who did not consent to the Gulf War, put the Holy See at the forefront of nations and states opposing the American war in Iraq.

John Paul II sealed this commitment to peace early on in his papacy through the Meeting of Assisi in October 1986. This meeting of the leaders of different religions was remarkable for its prophetic value. Again, on January 24, 2002, leaders of most of the world’s major faiths carried lighted oil lamps signifying their hopes for global peace, as they joined Pope John Paul II at a ceremony marking the World Day of Prayer. Clerics of faiths ranging from Christianity to Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism and traditional African religions called for an end to all war, terror and violence. “Violence never again! War never again! Terrorism never again!” urged John Paul II, who had invited the religious leaders to the birthplace of St. Francis to pray for peace, following the September 11 terrorist attack on the United States.

The ceremony was attended by some 3,000 guests, including the Italian President, the Prime Minister and members of the Vatican’s diplomatic corps. John Paul II, who was suffering from the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, appeared in fine form throughout the day, playfully waving his cane to the crowds as he left Assisi.

Then, when John Paul’s health failed completely, the world held its breath in the face of such human suffering. When he died, millions started flocking to Rome to bid farewell to the greatest church leader of the century. His funeral, with the immortalized image of the bare wooden coffin and the Book of the Gospel on top of it, its pages turning in the wind, was a world event that touched the imagination of millions and gave food for thought to even the most superficial of human beings. It was during the funeral when the demands “Santo subito!” (Let he be declared saint at once!) were put forward by the crowds. At that moment, it seemed unlikely. Now, only nine years later, it is a reality.

THE MARK OF HOLINESS

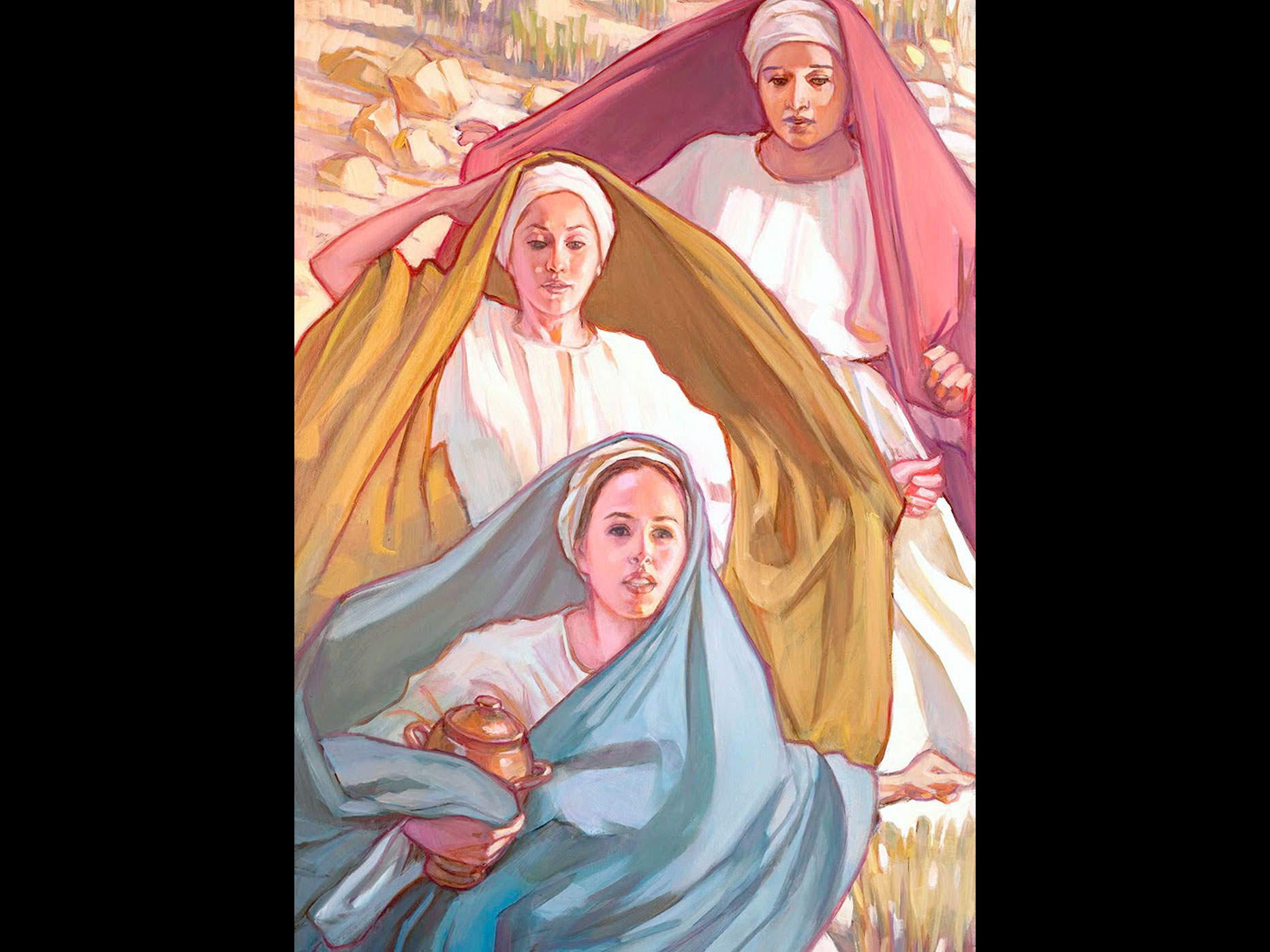

In the late sixties, the famous Jesuit singer-priest Aimé Duval, in his song Par la main, described the Church as the pilgrim people of God, moving slowly along the great plains, battered by the winds and the storms, defenseless but brave: “They haven’t got their Father with them, but they know well their route; they haven’t got their Father with them, but their Mother holds them by the hand.” Out of the fortress, in the open, the Catholic Church presents to the world her vulnerability.

It is Christ’s embrace for all, but especially for the victims, that the Church is offering, notwithstanding her weaknesses and sin. It is Christ’ presence and love that are found in the Church: these allow humanity to overcome the mystery of evil. If Christ’s holiness was missing in the Church, it would be impossible.

Starting with St. Pius X, all the popes of the 20th century are luminous examples, not only of outstanding learning and leadership, but especially of holiness. If John XXIII and John Paul II reached the stage of canonization at the same time, given the urgent demand of their overwhelming popularity, a similar, outstanding virtue must be attributed to the popes who led the Church in their wakes: Paul VI and Benedict XVI, respectively. If their more reserved and introverted nature did not merit for them popular recognition, their moral stature is enormous and more than makes up for their lack of popularity. One can only marvel at how God has bestowed these troubled times with a string of such champions!

The Church is the realization of God’s will before the end of time. All the members of the Church are called “a priestly people” because the holiness of their life is the only worship that God expects. God is persistent in His love. The sins of the Church will never destroy Jesus’ faithfulness. There is no danger that God might be disappointed because the Church is Christ, she is identified with Jesus Christ. Her faithfulness is that of Christ, and the power that moves her is that of the Spirit of Christ. The new Saints John XXIII and John Paul II are witnesses to all this.