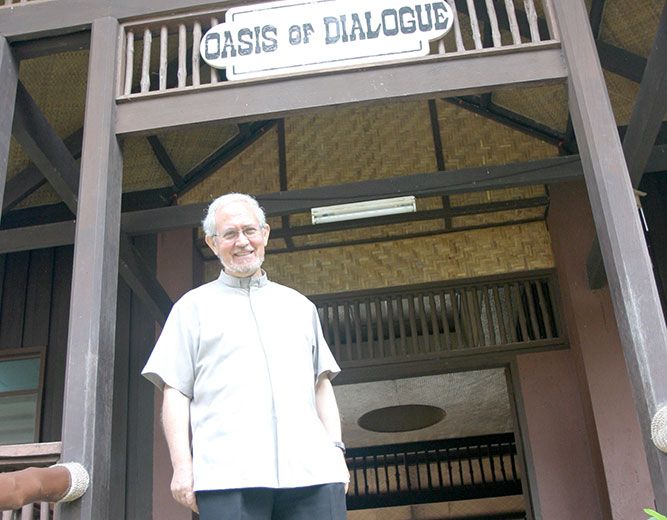

Father Sebastiano D’Ambra, a PIME missionary born in Italy in 1942, landed on the island of Mindanao in 1977. Soon after his arrival, he concentrated his attention on the conflicts between the tribal groups and Muslims, on one hand, and the Islamic rebels and the government, on the other hand.

The result of this commitment was the birth of Fr. D’Ambra’s best-known creation, the Silsilah Dialogue Movement in Zamboanga City in 1984 and now widespread in various areas of the country and abroad.

Father D’Ambra, how did this passion for dialogue with Islam come about?

In my first years of presence in the Philippines, I found myself working for the peace process with some rebel groups. This involvement, however, disturbed someone so much so that I had to leave the country because of the many threats I was receiving.

Back in Italy, I enrolled in PISAI, the Pontifical Institute for Arab and Islamic Studies, to deepen my knowledge of the Muslim religion, in particular Sufism. It was two years of profound reflection, study and prayer. Back in the Philippines, I settled in Zamboanga, an important multicultural and multireligious city in the south of the country, and there I started a movement called Silsilah, in Arabic “bond.”

What is the core of your commitment?

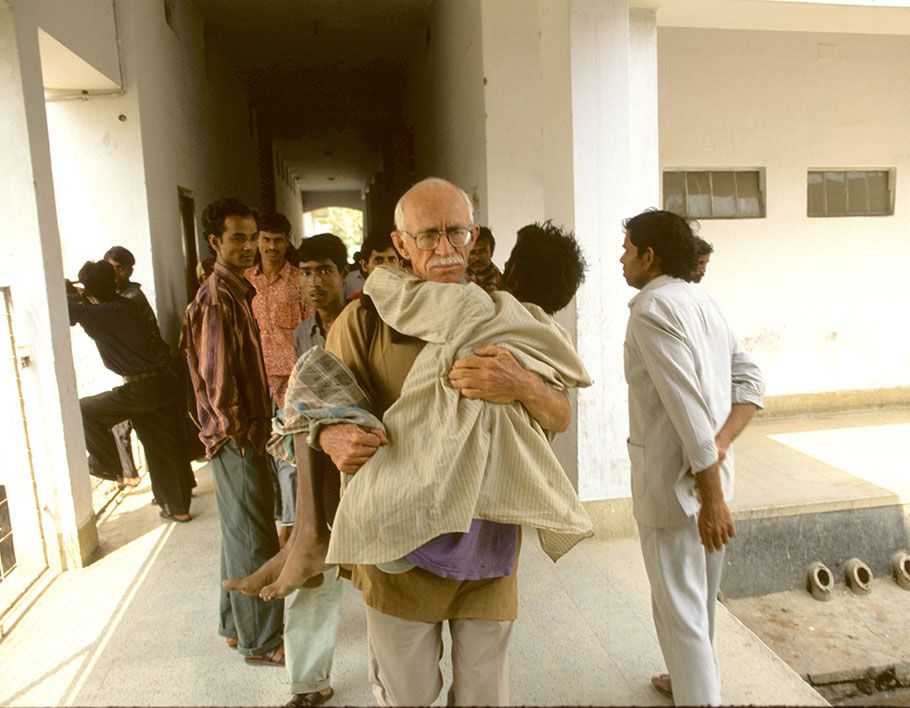

We started with weekly meetings of reflection and spontaneous prayer. Then the training courses were born, aimed first at our group and then extended nationally. Today Silsilah is a recognized course that has trained thousands of leaders engaged in the Church and politics, not only in the Philippines.

Then came the Silsilah Forums, which bring together our alumni in various cities of the country. Under the guidance of a Christian and a Muslim coordinator, awareness and solidarity activities are carried out. The Emmaus experience is dedicated to concrete actions for the most needy: a small group of consecrated lay Catholics, who share our spirituality, have created an elementary school in a very poor area, on an island inhabited by Muslim inhabitants, and seven small schools here in the city.

And again, the “Interfaith Council of Leaders” brings together religious members esteemed by their respective communities who carry on the request for dialogue and intervene in social dynamics as needed, in a process aimed at creating “Harmony Zones.” And, of course, we have many prayer initiatives, which are the basis of all our work.

You are currently the secretary of the Commission for Interreligious Dialogue of the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines: how are you working at the local Church level?

Not all our bishops and priests are convinced of the opportunity of dialogue: some say it openly. In preparation for next year, I have written a book that will become the official manual for formation in all dioceses and religious institutes.

At the center is the document on human brotherhood signed by Pope Francis in Abu Dhabi. We will therefore do formation days, both for the clergy and in schools, while I am compiling an inventory of the various groups, from universities to NGOs, which already operate on these issues so that this extraordinary year’s work can then continue ordinarily.

Recently, I presented to the Bishops Conference the proposal to finally recognize Father Salvatore Carzedda from PIME, a collaborator of Silsilah who was murdered in 1992 as a martyr. Some new testimonies reaffirm that Father Salvatore was killed precisely for his commitment to dialogue, opposed by some more radical groups.

How is the situation in Mindanao today?

Although the progress made in recent years cannot be denied, this is a moment of confusion and fear, in which Christians fear the growing influence of the most radical and violent Islamist groups while Muslims themselves are increasingly divided within them.

If there are those who are tired of conflicts and would like a more peaceful life, the extremists also do not give up, foddered from abroad. A great effort is also underway to Islamize Christians. And the violence periodically explodes: it happened five years ago in Zamboanga then two years ago in Marawi.

This is an ancient problem: Muslim rebels claim these lands. President Duterte has finalized an agreement with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, establishing the “Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao,” a more concrete result than in the past.

But we know that it is not the definitive solution, because a certain division can already be seen within the various rebel groups. The only way is to work patiently at the grassroots level to promote coexistence–a difficult challenge that we must not be afraid to face. Published in Mondo e Missione