To be an active Catholic in Italy, in the years immediately following the end of World War I, often meant to become subject to the violent pressure both of the Communists and of the rapidly emerging Fascist Party. Catholic youth, belonging to Church organizations, were expected to be courageous and resourceful in the public manifestations of their loyalty to the Church and in the defense of their Christian ideals. This is what can be seen in the life of Pier Giorgio Frassati, a university student from a well-to-do family and a committed member of Catholic movements.

One day, as he was participating in a Church-organized demonstration in Rome, he bravely withstood police violence and rallied the other young people by grabbing the banner which the police had knocked out of someone’s hands. He held it even higher while using the pole to ward off their blows. When the demonstrators were arrested by the police, he refused the special treatment that he might have received because of his father’s political position, preferring to stay with his friends.

Despite the many organizations to which Pier Giorgio belonged, he was active and involved in each, fulfilling all the duties of membership. Pier Giorgio was strongly anti-fascist and did nothing to hide his political views. He used to say: “It is not those who suffer violence that should fear, but those who practice it. When God is with us, we do not need to be afraid.” One night, a group of fascists broke into his family’s home to attack him and his father. Pier Giorgio beat them off single-handedly, chasing them down the street, calling them “Blackguards! Cowards!”

LOVE FOR THE POOR

Pier Giorgio Frassati was born in Turin, Italy on Holy Saturday, April 6, 1901. His father, an agnostic, was the founder and director of the liberal newspaper La Stampa, and was influential in Italian politics, serving a term as senator and, later, was Italy’s ambassador to Germany. Pier Giorgio grew up in the usual activities at the school and in sports. But since an early age, he showed a great love for the poor.

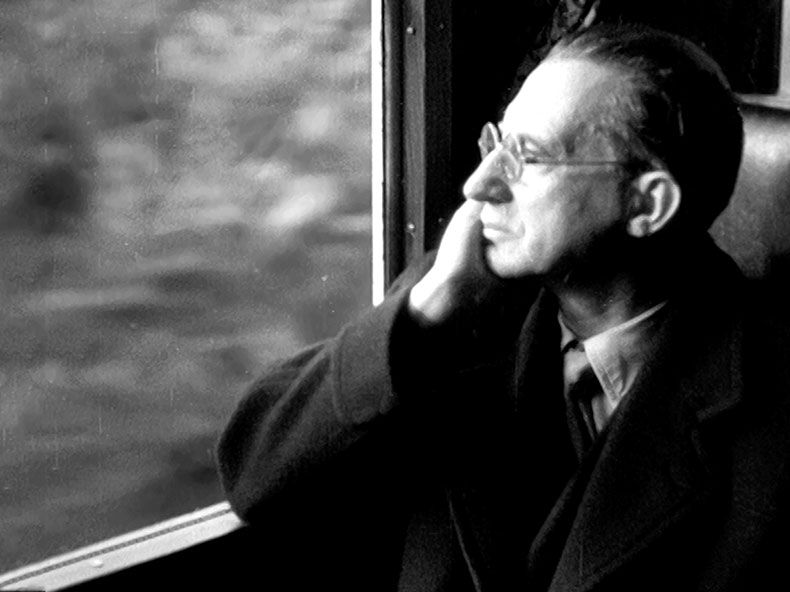

Although the Frassati family was well-to-do, the father was frugal and never gave his two children much spending money. What little he did have, however, Pier Giorgio gave to help the poor, even using his train fare for charity and then running home to be on time for meals in a house where punctuality and frugality were the law. When asked by friends why he often rode third class on the train he would reply with a smile: “Because there is no fourth class.”

When he was still a child, a poor mother with a boy in tow came begging at the Frassati home. Pier Giorgio answered the door, and seeing the boy’s shoeless feet gave him his own shoes. As a graduation gift, given a choice between money or a car, he chose the money and gave it to the poor. He obtained a room for a poor old woman evicted from her tenement, provided a bed for a consumptive invalid, supported three children of a sick and grieving widow.

At the Italian embassy in Berlin, he was admired by a German news reporter who wrote: “One night, in Berlin, with the temperature at twelve degrees below zero, Pier Giorgio gave his overcoat to a poor old man who was shivering with cold. When his father scolded him, he replied simply and matter-of-factly: ‘But, you see, papa, it was cold.’”

THE LIFE OF A MYSTIC

Pier Giorgio also spent time in the countryside with friends; mountain climbing was one of his favorite sports. On these outings, however, the young friends did not hesitate to share with him their religious inspiration and spiritual lives. He often went to the theater, to the opera, and to museums. He loved art and music, and could quote whole passages of the poet Dante.

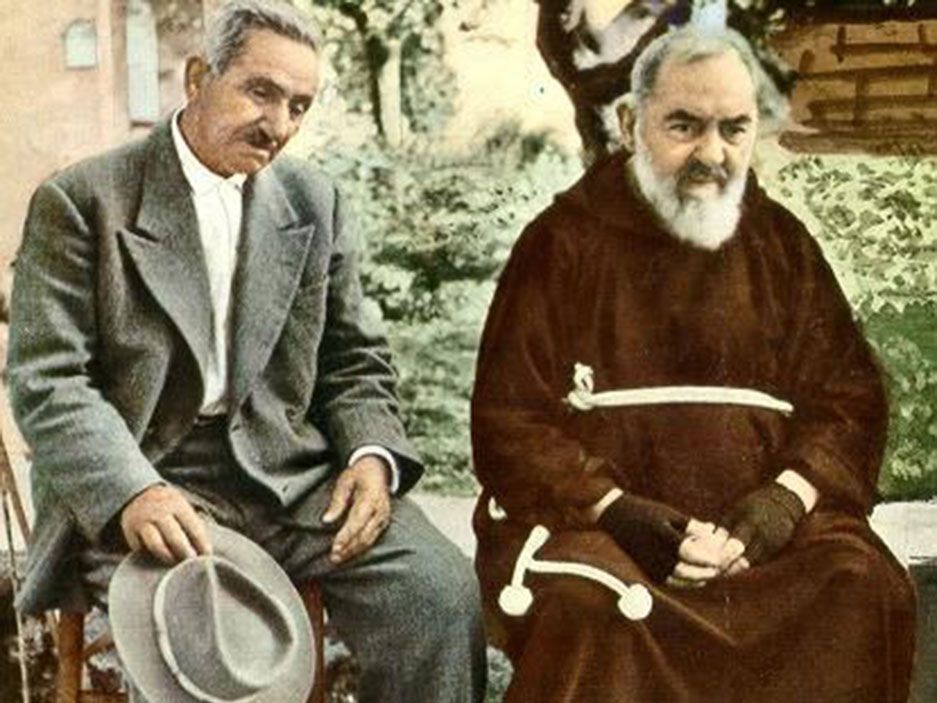

But beneath the smiling exterior of the restless university student was concealed the amazing life of a mystic. Love for Jesus motivated Pier Giorgio’s actions. He assisted at Mass and took communion daily, and made frequent nocturnal adoration. He liked to meditate on St. Paul’s “Hymn of Charity” (1 Cor 13) and on the writings of St. Catherine of Siena.

He decided to become a mining engineer, studying at the Royal Polytechnic University of Turin, so he could “serve Christ better among the miners,” as he told a friend. Although he considered studies his first duty, they did not keep him from social and political activism. In 1919, he joined the Catholic Student Foundation and the organization known as Catholic Action. He became a very active member of the People’s Party, which promoted the Catholic Church’s social teaching based on the principles of Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical letter, Rerum Novarum. “Charity is not enough, we need social reforms,” he used to say.

ROLE MODEL FOR THE YOUTH

Just before receiving his university degree, Pier Giorgio contracted poliomyelitis, which doctors later speculated he caught from the sick whom he tended. Neglecting his own health because his grandmother was dying, Pier Giorgio died at the age of 24 on July 4, 1925 after six days of terrible suffering. His last preoccupation was for the poor. On the eve of his death, with a paralyzed hand, he scribbled a message to a friend, asking him to take the medicine needed for injections to be given to Converso, a poor sick man he had been visiting.

His family expected Turin’s elite and political figures to come to offer their condolences and attend the funeral; they naturally expected to find many of his friends there as well. They were surprised, however, to find the streets of the city lined with thousands of mourners as the cortege passed by: they were the many people Pier Giorgio had directly helped during his brief life. He was originally buried in the family crypt in the cemetery of the city.

His mortal remains, found completely intact and incorrupt upon their exhumation on March 31, 1981, were eventually transferred from the family tomb to the cathedral in Turin. Pope John Paul II, after visiting his original tomb in the family plot, said in 1989: “I wanted to pay homage to a young man who was able to witness to Christ with singular effectiveness in this century of ours. When I was a young man, I, too, felt the beneficial influence of his example and, as a student, I was impressed by the force of his testimony.” On May 20, 1990, in St. Peter’s Square which was filled with tens of thousands of people, the Pope beatified Pier Giorgio Frassati, calling him the “Man of the Eight Beatitudes.”

PASSIONATE POLITICIAN

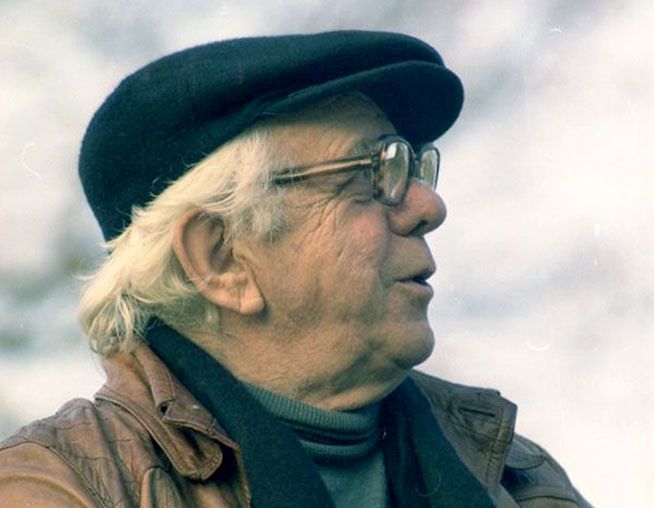

On August 17, 1954, Vinicio Dalla Vecchia, medical doctor and assistant lecturer in the Institute of Medical Pathology of Padua University, was climbing a difficult mountain of the Dolomites in Northern Italy. With him was his cousin, a Salesian priest. The solitary climbing was destined to end in tragedy. Because of unknown reasons, they both fell to their death. Vinicio was only 30 years old – a promising member of his profession and especially an exceptional operator in the field of Catholic Action and in politics with the Christian Democrats.

He was a passionate rock-climber and had written: “The desire to see and know these beautiful mountains is like a flame which bursts from the bottom of my heart. It is impossible for me to resist the powerful fascination that emanates from those naked mountain walls… I wait impatiently for the moment to come of setting out for the climbing. For me, it is to know, to see realities which recall my soul to the contemplation of God’s greatness and wisdom, to experience emotions that make my heart throb.”

Vinicio Dalla Vecchia was born near Padua, Italy, from a working class family, on March 23, 1924. He grew up in the school and in the parish, harmoniously combining studies and apostolate. During his university course, he joined politics. He graduated as a medical doctor and surgeon and soon started a career in the University of Padua itself.

At the time of his sudden death, Vinicio was engaged to Maria. A bunch of love letters reveals the fiber of this Christian lover. He wrote: “In this moment, it is easy for me to create around and inside me a “silence zone” where the dearest thoughts and feelings gather in order to be enriched in God’s light…Really, Maria, we must become good and without wasting time. Many people are expecting this from us. To draw closer to God: this is the objective. Any other objective has no value unless geared to this progress of the soul towards God.”

Vinicio’s love story for Maria is so beautiful because it enhances the whole of his affective life. The novelty of what he is experiencing is more than a generic falling in love. The emotional attraction he experiences is consistent with the great ideals for which he is living. His affective adventure becomes a key for reading the whole of his life. Our life of faith cannot be all in the head, it must become an emotional involvement; ideals and affection in Vinicio become one.

MODEL OF ENLIGHTENED DISCERNMENT

During his long commitment to politics and social action, Vinicio defined the social teaching of the Church as “truthful” and added: “In order to spread and defend it, we must know it and the greater our knowledge of it, the more relevant will be our action to spread it, because it will ever more shine on us the conviction that the social teaching of the Church is just, true and indispensable in order to foster peaceful co-existence and brotherhood among peoples.”

Mons. Giovanni Vaccarotto, postulator of the cause of Vinicio’s beatification which was opened in 2001, wrote: “I think that Venerable Dalla Vecchia may be easily proposed as model for a journey of faith and enlightened discernment. He was able to harmonize all the areas of his commitment: life, studies, politics and all the other choices he made in order to serve others. Somehow, he anticipated the reading of the signs of time, of Vatican II.

Vinicio knew how to use his beautiful mind in order to stay at his place, always looking at his polar star – Jesus in the Eucharist and the Virgin Mary – without modifying his personality, in full cooperation with and respect for the Church leadership, in full accomplishment of his total, solid, full lay status.”

Leon Bloy has written: “There is only one sadness: that of not being saints.” Vinicio pursued incessantly this ideal of holiness. He understood the importance of the Eucharist and prayer. Near the Faculty of Medicine he was attending at Padua, there is a little church. There, the medicine student Vinicio was going daily to ask the priest for Communion. He wanted to be a saint, but he also wanted to save souls. He wanted his schoolmates and friends to follow him along the road to holiness with the same passion as himself. Mons. Luigi Sartori, famous theology professor and Vinicio’s contemporary, candidly admitted: “I have lived fifty years more than Vinicio, but I am convinced that he has overtaken me in intensity of life.”