On June 3, 1963, Pentecost Day, the long agony of Pope John XXIII, the pope of Vatican II, came to an end at 19.45 hours. Ten days before, on Ascension Day, he had spoken to the pilgrims in Saint Peter’s square for the last time, as if sensing the coming death: “With our desire, we run after the Lord who goes up to heaven….” Immediately, the public appearances were suspended, the pope was ill. The whole world followed the pope’s terminal illness with trepidation… The end was approaching, but his mind remained lucid to the last minute.

Pope John’s death marked the climax of his pontificate and multiplied the consensus for a pope who had put in motion a phenomenon of unusual proportions as the Second Vatican Council. His death was experienced as belonging to the whole of humanity. It was a final witness of poverty, consistent with a lifestyle pursued with utter commitment. He had written many years before, in his last will: “Born poor, but from honorable and humble people, I am particularly happy to die poor. I thank God for this grace of poverty that I vowed in my youth, spiritual poverty as a priest of the Sacred Heart, and real poverty… In the hour of saying farewell, or better, good-bye, I remind all of what is dearest in life: the blessed Jesus and His Church, the Gospel of the Our Father, truth and goodness, benevolent, resourceful, patient, undefeated and victorious goodness.”

A historical choice

A trait of great significance in Pope John was the kind of peaceful strength by which he always expressed his convictions. Only during his rule as a pope, this strength appeared in all its disconcerting splendor. It was with this certainty, only ninety days after his election on January 25, 1959, that Pope John announced his intention of calling an ecumenical council. He made the announcement to the cardinals gathered in the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls, on the concluding day of the Week of Prayers for Christian Unity. He repeatedly stated that he wanted a new Pentecost to again bring the gifts of the Holy Spirit on the Church, renew her youth and respond to the “signs of the time,” opening her anew to her universal mission.

The Second Vatican Council has marked the history of the modern Church. It took place between 1962 and 1965. Blessed John’s successor, Pope Paul VI, had the task of bringing the Council to its conclusion. The discussion among the Council Fathers was intense and articulate, the arguing vivacious, under the unusual attention of the interested world media. The Council documents are solid contributions to the Church’s doctrine and tradition. The whole Church turned a glance of empathy towards the “joys and sorrows” of humanity, conscious of belonging herself to the scene of this world.

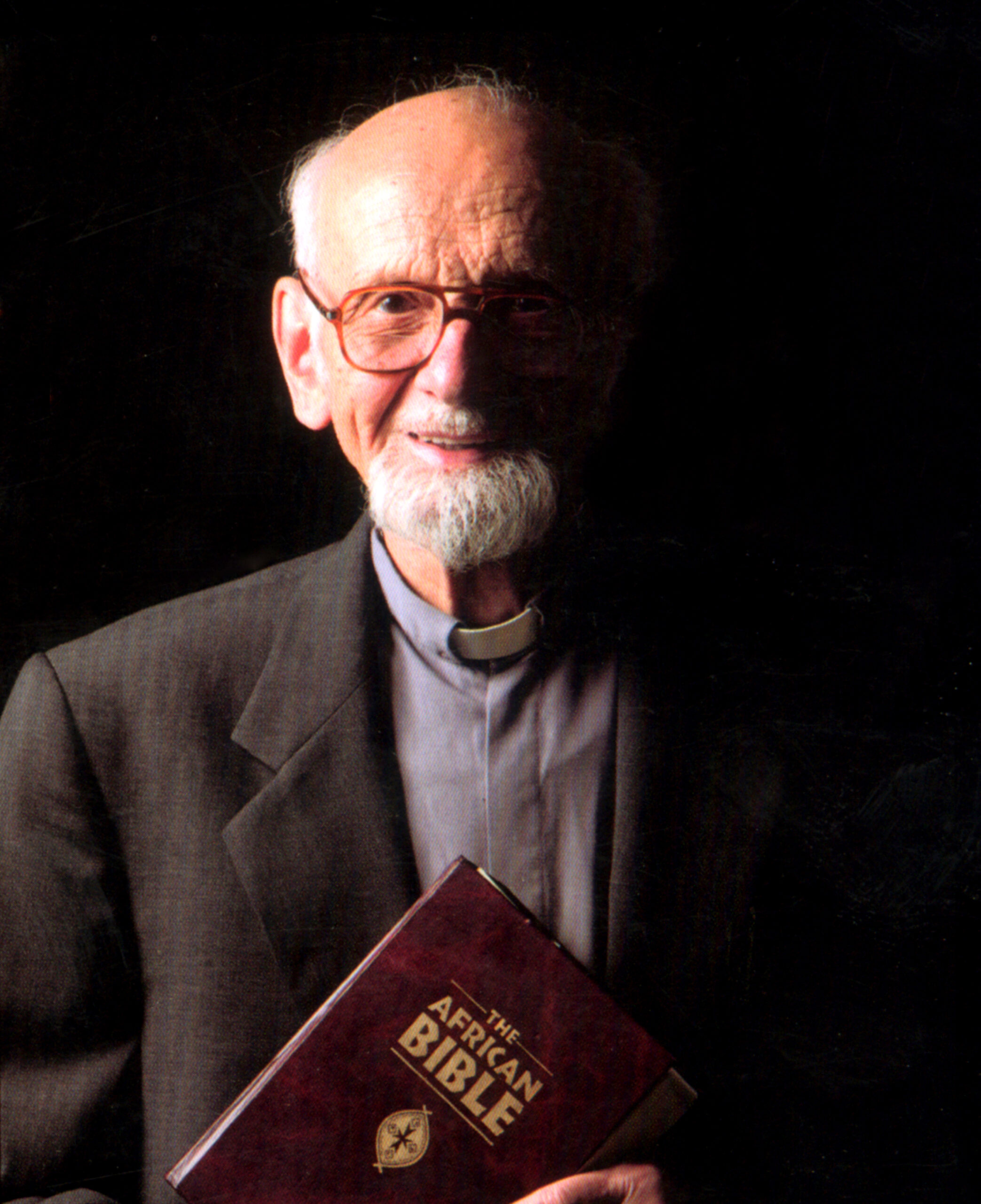

A renewed vision of the Church as the pilgrim people of God brought in evidence the colorful reality of the local churches already present all over the world, as the fruit of the gigantic missionary wave of the 19th and the first part of the 20th century. The liturgical reform enhanced the self-consciousness of the different local communities, empowered also by the renewed interest and appreciation of the Bible, God’s Word. But what appeared as a historical choice that overcame the impasse of centuries and really opened the horizon of the future was enclosed in three smaller documents.

With the decree “Unitatis Redintegratio” (The Restoration of Unity), the Catholic Church was now looking at the other Christian Churches as bearers of the same faith and was committing herself to the ecumenical cause. With the declaration “Dignitatis Humanae” (The Dignity of the Human Person), the Church was embracing the principle of freedom and, in this way, entering defenseless into the world arena, relying only in the power of God and in the self-evident goodness of the Gospel message.

With the declaration “Nostra Aetate”(In This Age of Ours), the heartwarming conviction of God’s universal salvific will made the Church look at the non-Christian religions as genuine vehicles of “seeds of the Spirit” and enter decidedly into the way of tolerance and dialogue. These positions are still vital after almost fifty years; they were embraced and carried forward by the forceful witness of Pope John Paul II, in his exceptionally long pontificate, and are still Pope Benedict’s painstaking commitment.

Eve and the apple

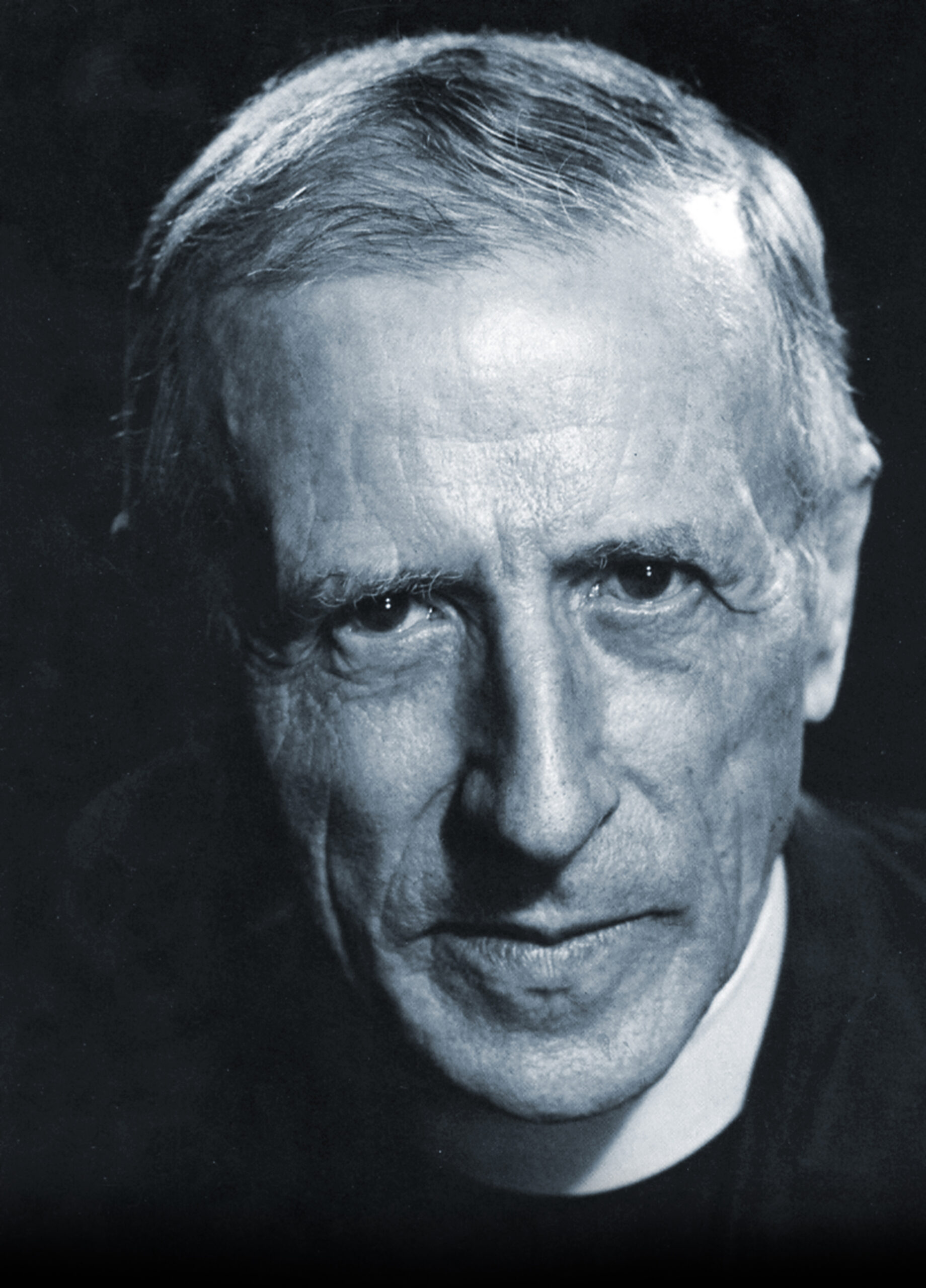

Pope John XXIII was born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli at Sotto il Monte, a village near Bergamo, in Northern Italy, on November 25, 1881. Son of a patriarchal family of farmers, he was marked, since his childhood, by a good, down-to-earth sense of realism and a profound, uncomplicated Christian faith. Very young, he entered the seminary, was ordained a priest at 23. He progressed rapidly in his ecclesiastical career first as the Bishop’s secretary, then at Propaganda Fide in Rome. Just before his priestly ordination, he had experienced military life because of the compulsory military service required by the state laws of that time and went back to the army as a priest during World War I, from 1915 to 1918, serving at the frontline as stretcher-bearer.

In 1925 he was made a bishop and sent to Bulgaria as Apostolic Delegate. He spent ten years in close contact with the Orthodox Christianity and other ten years at Istanbul, in Turkey, in the same capacity, dealing with the Muslim world. It was there that he weathered the World War II years and, in 1944, he was sent by Pope Pius XII to France as his nuncio. In all, he served 28 years in the Vatican diplomacy and that shaped his personality. It was from this experience that he acquired his openness towards cultural worlds different from his own and honed his tolerant and humane approach to people.

In Paris, during a state dinner to which he took part in his official capacity, a lady with a plunging neckline happened to be seated not far from him. In the course of the meal and the conversation, Msgr. Roncalli kindly offered an apple to the lady from the fruit bowl. To the puzzled look of the person seated near him, the nuncio whispered: “It was biting the apple that Eve realized that she was naked.” In 1953, he was made a cardinal and sent to Venice as patriarch. From there, God chose him to succeed the prestigious figure of Pius XII, on October 28, 1958. Then, the adventure of the Second Vatican Council began.

Mission in the open

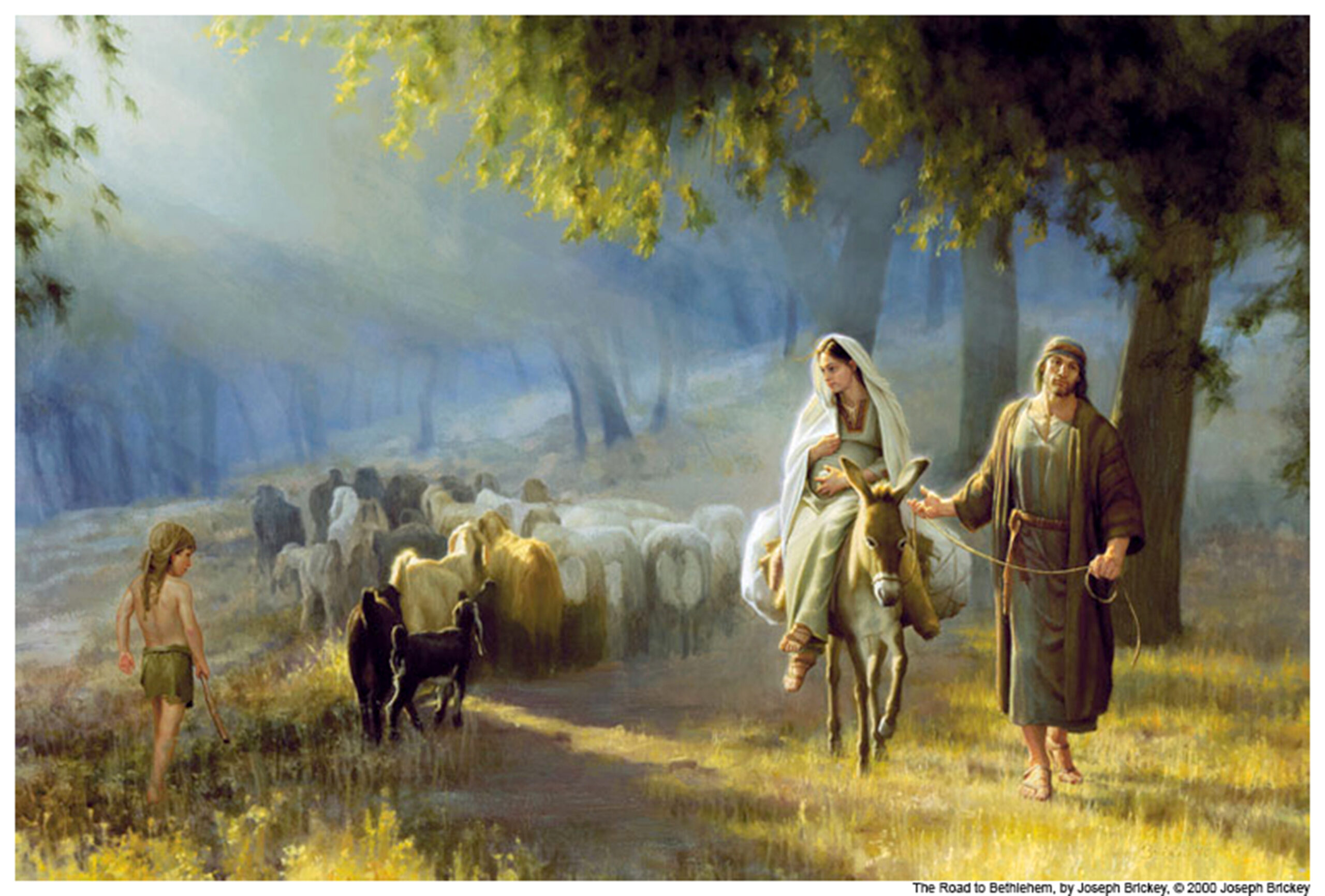

Blessed John’s ample, worldwide exposure in the years of his diplomatic service, foretells the opening to mission of the Council. “The Church, on her pilgrimage on earth, is by her very nature missionary, since, according to the plan of the Father, she has her origin in the mission of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.” With these words, at the beginning of the Decree on the Church’s missionary activity “Ad Gentes,” the Council opened new horizons for Mission: starting from the “Mission of God,” it showed Mission to be essential to the very nature of the Church, consequently involving every Christian in the universal responsibility for the spreading of the Gospel.

Contemplating mission already in God, it showed in a new light humanity’s efforts to search for God as already in operation because of the mysterious presence of the Holy Spirit, the protagonist of mission. It, therefore, became imperative for the Church’s mission to join inculturation and dialogue to the proclamation of the Gospel. Clothed in a new humility, missionaries make their own the motto: “Our first task in approaching another people, another culture, another religion, is to take off our shoes for the place we are approaching is holy. Leste we forget… that God was there before our arrival.”

In the late sixties, the famous Jesuit singer-priest Aimé Duval, in the lyrics of his song Par la main, describes the Church as the pilgrim people of God moving slowly along the great plains, battered by the winds and the storms, defenseless but brave: “They haven’t got their Father with them, but they know well their route; they haven’t got their Father with them, but their Mother holds them by the hand.” Out of the fortress, in the open, the Catholic Church presents to the world her vulnerability. But side by side with all the limits of her wounded humanity, there is something radically greater than sin in her. If the Church didn’t have to offer the world, especially the victims, Christ’s embrace, beyond all the evil that we can commit, we would then really be lost. For evil would be there anyway. But it would be impossible for us to overcome it.

The good pope

Pope John’s death was his greatest homily on the theme of Christian faith as a public virtue. For centuries, the conviction was taken for granted that what was relevant in the outstanding servants of the Church was almost exclusively their private virtue. At first sight, Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli appeared just a common, ordinary Christian. Yet, from him, emerges a rare consciousness of the simplicity of confessing the Gospel to everybody without arrogance or omission. His search for meekness became more acute especially as an answer to his position of authority. His daring grew with the growing of his pastoral responsibility.

Pope John’s life is marked by the unbreakable unity between his religious personality and his service as pope. His spirituality appeared to be “common,” inasmuch as it reflected the condition common to all Christians. A telling evidence of this is in the name by which people liked to call him: “Il papa buono” (the good pope). Good is the commonest adjective and that with the most profound meaning. Now that, with his beatification, he has officially entered the company of the saints, he points to the Church’s real strength.

The Church is the realization of God’s will, before the end of times. All the members of the Church are called “a priestly people” because the holiness of their life is the only worship that God expects. God is persistent in His love. The sins of the Church will never destroy Jesus’ faithfulness. There is no danger that God might be disappointed because the Church is Christ, she is identified with Jesus Christ. Her faithfulness is that of Christ, and the power that moves her is that of the Spirit of Christ.