In 1989, a series of radical political changes occurred in Europe, in the Communist Eastern Bloc, associated with the liberalization of the Eastern Bloc’s authoritarian systems and the erosion of political power in the pro-Soviet governments in nearby Poland and Hungary. After several weeks of civil unrest, the East German government announced on November 9, 1989 that all citizens of the Democratic Republic of Germany could visit West Germany and West Berlin.

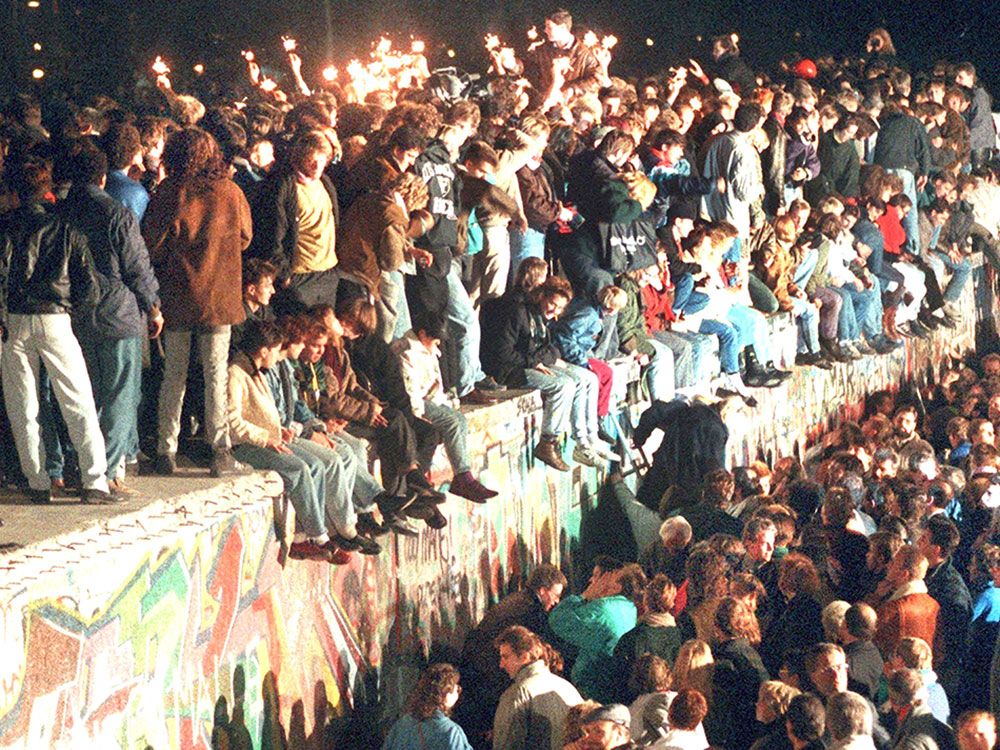

Crowds of East Germans crossed and climbed onto the Wall, joined by West Germans on the other side in a celebratory atmosphere. Over the next few weeks, euphoric people and souvenir hunters chipped away parts of the Wall; the governments later used industrial equipment to remove most of what was left. The fall of the Berlin Wall paved the way for German reunification which was formally concluded on October 3, 1990.

The noisy and frightful communist phenomenon that had started seventy years before did not end “with a bang but with a whisper” as T.S. Eliot would say. It ended by implosion: the end of the Soviet communism happened without bloodshed, by inner destabilization and consumption. If we think that less than fifty years before, in that very place, the collapse of Nazism had happened in an apocalyptic scenario of war and destruction, we cannot fail to perceive a kind of miracle.

Pope John Paul II in his encyclical letter “Centesimus Annus” (1991), while commemorating the end of a century since the landmark document of Leo XIII “Rerum Novarum,” dedicates a whole chapter by the title “1989” to this defining event. He attributes the peaceful end of the communist threat to prayer. The Blessed Virgin Mary, at Fatima, had exhorted to pray for the conversion of Russia and had declared: “In the end, my Immaculate Heart will prevail.”

The momentous landmark signed the victory of freedom and characteristically deserved to become a chapter in the famous letter mentioned above of one of the protagonists, Pope Saint John Paul II. Less than forty years later, however, the world, full of expectations, is sorely disappointed. The collapse of communism and the victory of freedom have not brought the prosperity, equality and wholesome progress they promised.

The “iron curtain”

The Berlin Wall was a barrier that divided Berlin from 1961 to 1989. Constructed by the German Democratic Republic, the Wall completely cut off, by land, West Berlin from surrounding East Germany and from East Berlin. The barrier included guard towers placed along large concrete walls, which circumscribed a wide area (later known as the “Death Strip”) that contained anti-vehicle trenches, “fakir beds” and other defenses.

Along with the separate and much longer inner German border, which divided East from West Germany, it came to symbolize the “Iron Curtain” that separated Western Europe and the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War. The West Berlin city government sometimes referred to it as the “Wall of Shame,” a term coined by mayor Willy Brandt.

The Eastern Bloc claimed that the Wall was erected to protect its population from fascist elements conspiring to prevent the “will of the people” in building a socialist state in East Germany. In practice, the Wall served to prevent the massive emigration and defection that had marked East Germany and the communist Eastern Bloc during the post-World War II period.

Between 1961 and 1989, the Wall prevented almost all such emigration. During this period, around 5,000 people attempted to escape over the Wall, with an estimated death toll ranging from 136 to more than 200 in and around Berlin.

End of communism

The beginning of the end started when, in the Soviet Union, the so called Perestroika came into existence and eventually prevailed. Perestroika was a political movement for reformation within the Russian Communist Party during the 1980s, widely associated with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and his glasnost (meaning “openness”) policy reform.

The literal meaning of perestroika is “restructuring,” referring to the restructuring of the Soviet political and economic system. It was an attempt to respond to the opposition to the communist system caused by the popular visit of Pope John Paul II to Poland and the consequent success of the “Solidarity” workers’ union of Lech Walesa that provoked the peaceful rejection of the socialist government under the control of Moscow.

Perestroika is rightly thought to be the cause of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the revolutions of 1989 in Eastern Europe, and the end of the Cold War. As the East Germans swarmed through the border, they were greeted by West Germans waiting with flowers and champagne amid wild rejoicing. Soon afterward, a crowd of West Berliners jumped on top of the Wall, and were soon joined by East German youngsters. They danced together to celebrate their new freedom. That practically signed the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Growing inequality

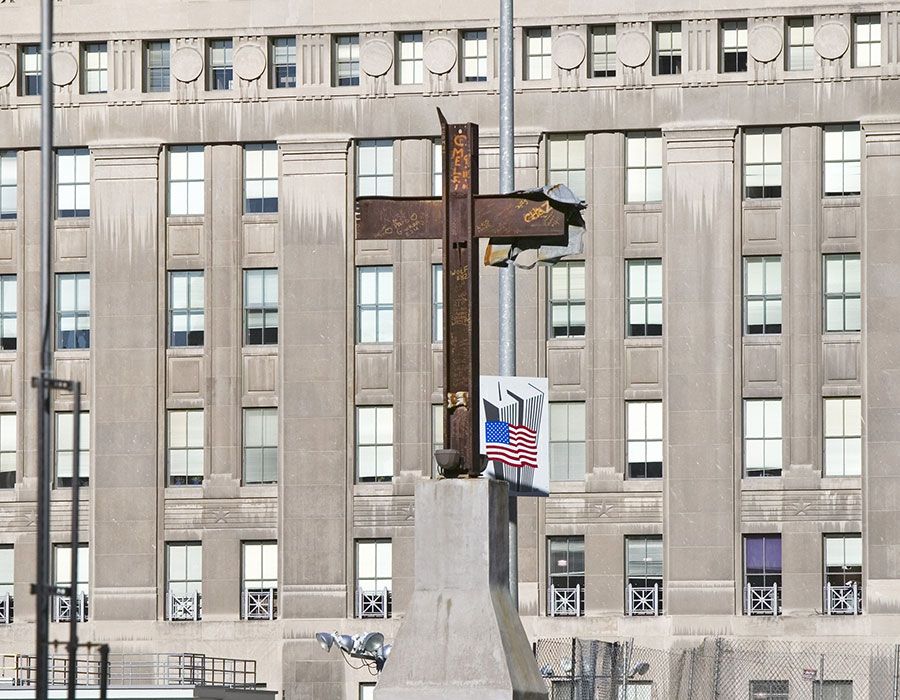

The Berlin Wall was intended to keep out the negative influence of the corrupt West in order for the experiment of the communist state to succeed. In reality, it was built to stop the people of East Europe to escape from the communist “paradise.” The Berlin Wall was the symbol of the lack of freedom. The “Iron Curtain” was imprisoning its inhabitants and turning the communist state into a jail.

The crumbling of the Berlin Wall was the triumph of freedom. At the moment when it happened, to the exalted population, it appeared as totally positive. But in the following years, the unbridled commercial freedom contributed to the practical collapse of the national borders under the impact of globalization. The unlimited abundance of consumer goods chased away penury but also equality. Enormous amount of wealth is now in the hands of the few and the masses of the disenfranchised are growing exponentially all over the world.

John Paul II evidently considered his encyclical letter “Centesimus Annus” as a new “Rerum Novarum.” Leo XIII had laid down the framework of social justice according to the Church’s teaching. John Paul II analyzes the failure of the communist system, built of principles opposite to those of the social teaching of the Church, on the background of the success of Western Europe. The Christian Democratic Parties had built the most egalitarian and progressive society, thus conferring an immense moral authority to the Pope’s social teaching.

Walls are going up again

Paradoxically, one enduring feature of the communist society which has survived the implosion of the Soviet state is the atheism of its population. Brought up in the absence of God to a materialistic outlook, the result of the crumbling of the Berlin Wall was not a religious revival but a craving for the material goods that the capitalist society was promising and delivering.

The Catholic Church, which had not only survived during the persecution but thrived, found itself in demobilization. The winter of vocations to the ministerial priesthood and religious life joined the dwindling mass attendance. The combination of freedom, availability of consumer goods and the sexual revolution revealed itself deadly poisonous for religion.

The walls are going up again in Europe and not only in Europe in the futile attempt of stopping the movement of the masses of poor people, the immigrants from the South of the world, overwhelmed by a kind of mass hysteria provoked by the social media now widely available to everybody, contributing to the dream of a better life in the North of the world.

Not only the relative stability and prosperity of the European countries are threatened by the unstoppable tidal wave of the economic refugees but the survival of their religious and cultural identity is endangered by the unexpected and unmanageable phenomenon.

The principle of freedom that the Catholic Church embraced with Vatican II and the disposition of tolerance and inclusion do not seem to work with a runaway world. The missionary edge is blunted and the initiative of conversions has passed to the Evangelicals who do not care about ecumenism and dialogue but are aggressive with their simple brand of biblical Christianity.

The principle of resistance

Pastoral strategy of mercy is self-defeating for expansion and even for the simple maintenance of the status quo. Christianity and mission have always thrived in resistance to the spirit of the world (Cf. Fuga mundi: the escape from the world of monasticism).

Pope John Paul II’s letter is prophetic in its criticism of the unbridled capitalism that is the consequence of the end of the polarization of the Cold War and which actually happened with globalization. He already speaks of “human ecology,” a concept which will be developed by the teaching of Benedict XVI and of the destruction of the habitat which was developed by the famous letter of Pope Francis “Laudato Si.”

Jesus Christ remains the only force capable of arresting humanity in their descent into barbarity. The future belongs to resistance. The survival of humanity depends on self-limitation. We have developed powers which are too much for the planet, for the animal world, the air, the water and the soil, and the humans themselves. To accept willingly and to embrace self-limitation, we need an inner wealth which compensates for the need of self-limitation and motivates it. Maybe the future belongs to a revival of spirituality.