The global war on illegal drugs has particularly gone brutal in the Philippines since the new president, Rodrigo Duterte, took office. Latest data from the Philippine National Police (PNP) revealed that, as of early October, at least 3,500 individuals were reportedly killed since Duterte rallied authorities to intensify efforts to crack down illegal drugs peddlers. Of this running statistics, at least 1,500 fatalities were identified as drug personalities killed during police operations while 2,000 others were classified as victims of extrajudicial or vigilante killings.

Duterte’s tough-on-crime attitude forced over 700,000 self-confessed illegal drug addicts and dealers to surrender to authorities for fear of their lives. But the Government was utterly unprepared to accommodate the offenders in overcrowded jails and limited rehabilitation facilities. They were eventually dismissed and told to go home after simply making an oath to stop drug abuse.

As the crackdown continues and the death toll climbs, public opinion is divided and the future of the biggest Catholic nation in Asia appears bleak. But hope is not completely lost. Community elders and citizens may have divided moral and legal views about the government’s anti-narcotics campaign but a handful of Church leaders offer a better perspective and solution. Thanks to Pope Francis’ declaration of the Jubilee Year of Mercy, the opening of parochial Doors of Mercy has a deeper meaning in the Philippines. The papal example of adopting refugees encouraged Filipino priests and bishops to open parish doors to drug offenders seeking refuge from the spate of state-inspired killings.

Mercy to the repentant

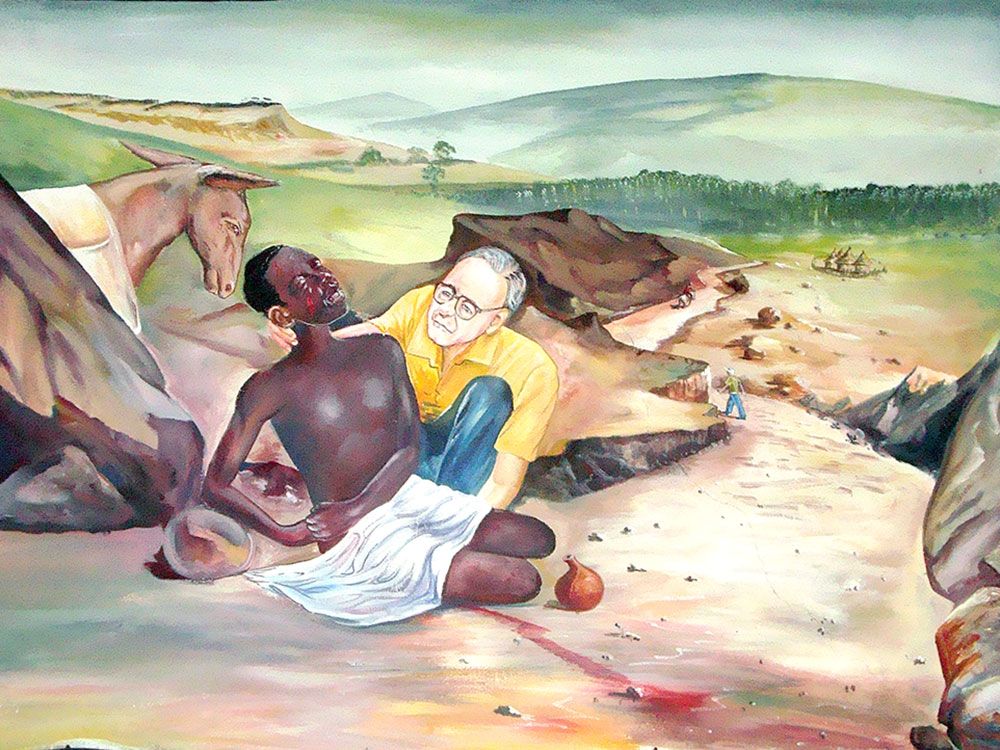

Archbishop Antonio Ledesma, S.J. was the first prelate to publicly welcome the delinquents within the Archdiocese of Cagayan de Oro in Southern Philippines. In a pastoral letter issued on Aug. 4 during the Feast Day of St. John Mary Vianney, the Prelate launched an archdiocesan program to provide immediate and long-term rehabilitation and intervention after at least 4,000 offenders surrendered to the authorities. The program kicked off on Aug. 22 with a full day of recollection, penitential service, confession and procession to Saint Agustine Metropolitan Cathedral, where a ceremonial opening of the Door of Mercy was held to symbolically welcome the repentant lawbreakers.

“As a Church, we cannot remain indifferent to this reality,” Ledesma pointed out. “Pastoral charity urges us to concretize the challenge of this Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy. Communities of faith are called to become ‘islands of mercy’ and ‘field hospitals,’ in the words of Pope Francis… [Thus] I am asking all pastors in the Archdiocese to open available facilities such as churches and parish halls for community-based recovery programs. I also enjoin all ministries, religious organizations and lay ecclesial movements to be actively involved in these collaborative efforts to accompany responders or recoverers, together with government agencies, NGOs and private institutions.”

Programs for drug offenders

In Metro Manila, Novaliches Bishop Antonio Tobias was the first prelate in the capital to initiate Church-assisted drug rehabilitation program for the faithful. With Tobias’ backing, Argentine priest, Fr. Luciano Feloni, launched a community-based healing program for drug offenders at the Our Lady of Lourdes Parish, a community in Caloocan City that saw three to five individuals get killed every week since Duterte declared the intensified war on drugs during his June 30 inauguration.

“It has to be crystal clear that the Church is 100 percent behind the President on this campaign against drugs because drugs are destroying the country. I come from Latin America and I know how it looks when drugs destroy a place. But, at the same time, we are against the killings,” said Feloni, who would say funeral Mass for the victims who were peculiarly killed in the same way by motorcycle-riding gunmen.

During the “Surrendering Day” held on Sept. 1 at Feloni’s parish, at least 20 drug offenders surrendered to the police. “Almost all the users are also small-scale pushers,” he shared. “They get their portion free but, at the same time, sell to others to get a little income. If you stop their business, they have no way to survive, no way to feed their children.”

This is why, according to the priest, the parish-led community-based healing program covers spiritual and psycho-social intervention with livelihood assistance, apart from basic family and parenting counseling. The parish likewise provides detoxification and rehabilitation to offenders. “There is no real program being offered by the government,” Feloni stressed out. “Once you surrender, you go home and it’s assumed you’ll stop being an addict. [But] you cannot stop addiction just by fear. It’s a sickness, and you need psycho-social intervention to cure it. If killing isn’t a solution, neither is surrender. It’s just the beginning. Unless you offer something, people cannot really change.”

During the “Surrendering Day,” Tobias assured help to those who surrendered to the Church. He expressed hope for their recovery, citing the salvation and healing of the sinners and sick people who went to Christ. The Prelate even offered the diocesan Bahay Pangarap (Dream House) property in Barangay San Agustin in Quezon City and a school building at the St. Joseph Parish of Barracks in Tala, Camarin, as venues for police-supervised intervention programs.

Just recently, Luis Antonio Cardinal Tagle followed suit with the establishment of the Restorative Justice Ministry of the Archdiocese of Manila. In a Sept. 15 address to the offenders, Tagle said the Archdiocese is opening its doors to those battling drug addiction to help them recover. “We welcome you with all our hearts and we pray that your humility to surrender and the decision to have a new life be blessed by God,” the Archbishop said. “We are here for you. Let us not waste life. It is important and it has to be protected and nurtured.”

In Manila, Fr. Tony Navarette pioneered the archdiocesan-led rehabilitation initiative at San Roque de Manila Parish. But due to scarce resources, he said urban poor communities lacking access to health care and drug rehabilitation centers will be prioritized. “The Church failed to address the issue before,” the priest said. “We failed to be a companion to these people, that’s why we are now trying all that we can do, given the urgency of the need.”

Personal encounter

Meanwhile, in Northern Philippines, particularly in the province of Nueva Ecija, Fr. Arnold M. Abelardo, C.M.F., took the mission of protecting people in crisis personally. The Claretian missionary, who is taking up his post graduate study on counseling in Manila, regularly goes to the province for his practicum work at the Ako ang Saklay (I Am the Crutches) Center in San Antonio town.

But one evening on his way to the town, Abelardo drove by a dirt road where an unidentified male was found dead. A few weeks later, Abelardo met the man’s wife who asked for a job at the Center to be able to feed her three children. “I think my encounter with that dead body on the road and my encounter with his wife were like personal calls of the Lord for me to do something, that I cannot just critic the government or those who are involved in drugs. I have to show and offer an alternative,” he said.

And Abelardo did. The priest offered his background in counseling and training as a priest to help the regional police establish a drug rehabilitation facility aptly named Bahay Pag-asa (House of Hope) inside the PNP regional headquarters in Cabanatuan City. On Aug. 24, Abelardo addressed the first batch of 30 drug addicts and peddlers who were admitted to the facility. With Abelardo’s assistance, a 30-day live-in program covering exercise, prayers, Bible study, and psycho-social processing was designed. “The problem of drugs cannot be solved by the police forces alone,” he stressed out. “The police are not trained to do rehabilitation; they are trained to maintain peace and order, to arrest and, if assaulted, to defend themselves. Rehabilitation and advising are not part of their training.”

As such, volunteer guidance counselors from the Saklay Center will facilitate assessment and processing of the offenders. “After a month of processing, we will assess. If, in the assessment, we find that there is more need for psychological and psychiatric intervention, then we can refer them to specialists.”

At the same time, Abelardo also opened the Saklay Center as a facility for families who underwent trauma due to drug addiction or due to the killing of their relatives because of the government’s anti-narcotics war. “The killings are causing fear and trauma to people,” he said. “At the same time, those who are affected should know that there are places, centers, parishes and halls that will welcome them and will not judge them.”

Abelardo also offered to train village health and social workers at the Saklay Center to help other villages replicate what is being done at Bahay Pag-asa. He also flew to Tacloban City to facilitate 50 religious women n psycho-social and psycho-spiritual approach to drug prevention and moral recovery. “What is important is we are starting something,” he pointed out. “You have to look at the drug issue as a health issue. It also covers the physical and mental well-being of the person.”

Given the government’s limited facilities and manpower to address the surge of drug offenders, Abelardo said the Church is morally obliged to step up and offer help. “I believe the Church is more capable because we have space in our parishes. We have priests and nuns who can give advice. And we have parishioners, who are psychologists, doctors, teachers and counselors; we can organize to help,” he explained.

Offer help rather than blame

Despite the divided public opinion on the morality and legality of Duterte’s campaign, Abelardo said citizens should contribute rather than criticize. “The drug crisis cannot be solved by merely stopping the killings,” he claimed. “Let us not stop by just saying ‘stop the killing.’ Let us do our part to solve the problem because, at the end of the day, it is a family issue affecting our communities.”

“Drug addiction has to be addressed by the whole community. When someone dies, the whole community gathers to mourn and to pray for the dead. When someone is celebrating a wedding, the whole community gathers to celebrate. When there is a fiesta, the community gathers and celebrate. I think when someone is in crisis, the community should gather as well to help and not to judge.”

He also urged fellow priests to help out instead of joining the blame game. “It is very timely to make the parishes’ door of mercy open to people in crisis because of drug problems,” he pointed out. “We cannot remain indifferent. We cannot just pray for them or attack the government. We have to show compassion and we have to offer an alternative.”

Duterte’s anti-narcotics campaign may have earned him critics around the globe. But Abelardo said he prefers to believe in the authorities’ intent to solve the drug crisis. “I think the President is serious about solving the problem of the country and I would like to believe that he cares about our youth. It is also unfair to assume that police are abusing their authority and to blame them for the deaths. Our policemen are also people of faith who have conscience and families of their own,” he pointed out.

The PNP claimed that the government’s anti-narcotics campaign has cut 70 percent of the illegal drugs supply in the country, but officials offered no concrete evidence to backup their assertions. What is only certain is that the killings, whether warranted or not, will continue until Duterte has punished the last drug lord or street peddler in a country of 101 million people.