The Church has always struggled about involvement in politics. For many centuries, in Western Europe, the Church was either the political power or in alliance with the political world. Later on, with the emergence of the French revolution and Illuminism, the Church was asked to take a step back. Some believed that there should be separation between religious beliefs and policy making; others wanted the Church to disappear altogether. With the advent of modern democracy, the tenet of separation of State and Religion has become widely accepted, even within the Church. The issue became very important in the 1980s. Many priests got involved in political parties in Asia, Latin America and Europe. The Vatican intervened in some cases to support their work, in others to forbid.

One such internationally renowned figure is Father Ernesto Cardenal, a Trappist priest who got involved with the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua. Soon after the fall of Managua, in 1979, he was named Minister of Culture by the new regime, a post he kept until 1987. When Pope John Paul II visited Nicaragua in 1983, he openly scolded Cardenal, on the Managua airport runway, for resisting his order to resign from that government. The Pope admonished Cardenal: “Usted tiene que arreglar sus asuntos con la Iglesia” (You must mend your position with the Church). Yet, in other cases, the Vatican ignored or even supported the involvement of priests in politics. At that time, many criticized the higher officials of the Church claiming that they were involved in political affairs, while asking priests and bishops to stay out of politics. Different is the issue of political commitment for the laity. However, even in this case, the Church has intervened, many times, to clarify how and when a faithful should get involved in politics.

The famous coin

One of the most quoted Gospel passages regarding political involvement is Matthew 22:15-22. There, the evangelist says openly that “Pharisees went out and laid plans to trap Him in His words.” They told Jesus that they considered Him a man of integrity and a good teacher. Then, they asked Jesus if it were right to pay taxes to Caesar or not. Jesus responded by accusing them of trying to trap Him, and by asking them to describe a coin: “Whose portrait is this, and whose inscription?” The Pharisees answered “Caesar’s,” and Jesus retorted: “Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s.” At first sight, it seems that Jesus declared a clear cut separation between the affairs of the State – Caesar – and those of religion. People should submit to earthly authority – paying a tribute is a way to recognize submission – as much as they do towards God. Yet, at a closer look, this Gospel is much more profound than it seems.

Jesus asks for a coin suitable to pay the tax. This was a denarius, a Roman coin. The denarius had a portrait of Augustus Tiberius and the inscription “Ti Caesar Divi Avg F Avgvstvs,” meaning Caesar Augustus Tiberius, son of the Divine Augustus. This inscription claimed Augustus a god, and so his son Tiberius, of divine origin. Accepting the use of this coin meant bordering idolatry. In fact, there is only one God, and no human can claim to be God. In answering that, they saw Caesar (by this time, the name Caesar signified the Roman ruler of the day), the Pharisees recognized in the head of state a person of authority. They did not seem to mind the fact that this Roman emperor claimed a divine origin. In reality, the image on the coin is first of all the image of a person, and the person belongs to God, not to the emperor. Jesus’ answer is now clear: if, in the person, you see the ruler, submit to that ruler; but if you see, first of all, the person, remember that we are to behave according to God’s rules above human ones.

This passage of the Gospel does not reflect a division of temporal and religious powers. On the contrary, Jesus underlines the superiority of God’s reign over secular power. And He does that by pointing to the Biblical tradition and teaching. Jesus’ response is still important today, especially in situations similar to that of the Holy Land in Jesus’ times. Palestine was then occupied by foreigners who imposed a culture clashing with that of the local people. They also perpetrated many injustices, suffocating any protest in blood.

The person at the center

God’s plan for the human being is not to have him oppressed by fellow people. In the creation narrative (Gen 1), God put order in the primordial chaos, and then creates ever more complicated beings. The last creation is the human being. This means that the person is the highest point in the universe. On the seventh day, God rests. The word used here in the original Hebrew is “shabbat,” which means to stop working. Indeed, in modern Hebrew, shabbat means also to strike! Once God created Man and Woman, He decided to stop and to live in harmony with the people He created. All the days of the creation narrative start and end. The seventh day, the one God spends with the whole creation, does not end. God makes it holy and endless (Gen 2:1-4).

If we read the creation narrative not as a historical text but as the plan God has for creation, we realize that the meaning of these words becomes new. God has a plan to create the universe, to put an order towards one goal: to be in full communion with His creation. The person is the highest point of creation; what remains to be done is the journey that leads us human beings in full communion with God. This can be achieved only when we strive to be in full communion with our fellow human beings. All our human structures should help us grow in this awareness of God, support our struggle to build meaningful relationship, and give us a sense of direction in searching for wholeness and communion. When temporal powers do this, then they help our journey. When the leaders of the nations take a different direction, then they put a stumbling block on the path towards God.

New dispensation

Jesus’ response to the Pharisees points to this very direction. Our obedience is, first of all, to God, then to other powers. Any human decision that goes against God’s plan must be refused. This is why the Church is becoming more and more aware that it has a crucial political role. In the past, the Church was itself a political power. Today, it is called to influence policy making. The Church cannot spouse a political project, because all political realities have positive and negative aspects. Also, the faithful may find appropriate to exercise their political life within more than one political party. The Church has a duty to support political decisions, taking position on precise policies, not political visions per se. In this endeavor, the Church is guided by some values. As we have seen before, temporal power should organize society helping people to grow, offering a space for human development, and allowing people to have fulfilled lives.

The first criterion in evaluating temporal power is the respect of human rights. A nation where gross injustices are present, and where these are not tackled by the State, is a nation guided by wrong political principles. All citizens, but also foreigners present within a society, should enjoy human rights. These rights are spelled out in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights. The Declaration was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1948 in Paris. The world was recovering from the Second World War, a war where the rights of peoples had been ignored and trampled. The participating nations to the UN prepared the Declaration, which is the first global expression of rights to which all human beings are entitled. The Declaration has 30 articles, which have since been elaborated in other international Bill of Rights and treaties. This shows how human rights are not a fixed set of rules. Human rights change with our awareness of what being human means. The basic principles enunciated in the Declaration are so developed into more detailed rights of the person. It also means that human rights have a cultural aspect in them. For instance, freedom of speech might mean different things in Thailand and Chile. What remains important is that people have a forum where they can speak up freely, without fear for their safety.

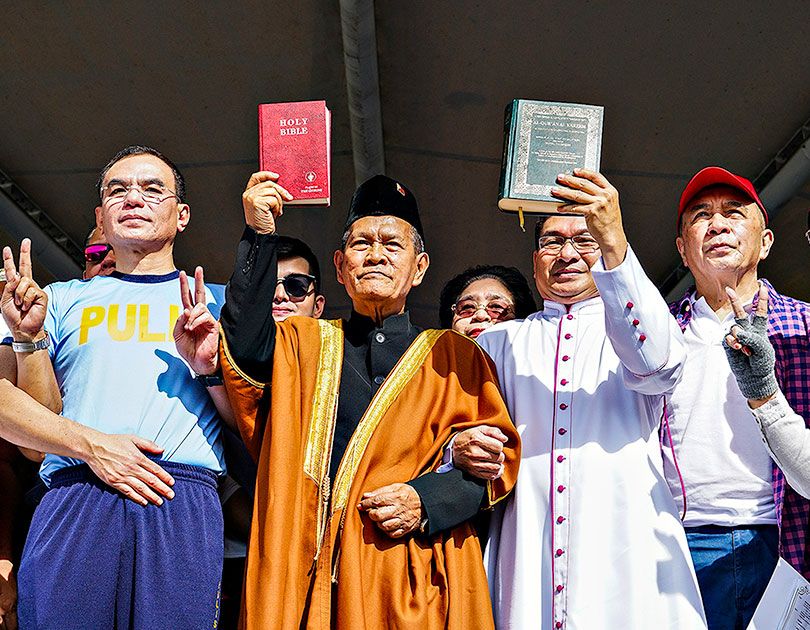

In this field, the Church has a duty to be present. Teaching about human rights, preparing leaders to know and respect the rights of the person, making the government aware of abuses, all these are political actions, and the Church must undertake them. Work in this area must be carried out by the faithful in all walks of life. Catechists will have to teach about the biblical foundations of the rights of the person. Politicians will have to consider these rights when preparing new laws and assessing older ones. Professionals need to constantly evaluate that their decisions respect the rights of people. The leadership of the Church will need to guide the faithful in preparing documents and making materials available so that all may have a sure foundation for their reflection and action. In the past years, we have seen many local Churches taking the lead in the political reform of their countries. This was made possible by the huge work in preparing the grassroots and positive engaging with the temporal powers.

The majority share the crumbs

Another criterion to consider is that of development. People have a right to life, a dignified life. Today in the world, more than one billion people live under the line of absolute poverty. Two-thirds of the world population live in poor conditions. Many do not have access to piped water, health care, education, food security, and many other basic services. Some say that it is impossible to afford everyone with the same level of development, that there will always be a small group of rich people and a large group of poor. In reality, our development model needs reassessment. The neo-capitalist model and the multinational approach have created a great disparity. In most countries, a small minority have access to the vast majority of resources. The majority, instead, have to share the crumbs. The millions of poor are the new slaves needed to make sure that the rich can have what they want. In the recent past, we have seen many signs that this development model does not work. Two simple examples are: coltan and oil.

With the advent of mobile communication, billions of telephones have been sold. Even in the remotest areas of the Earth, people now use mobile phones to communicate. This technology is good and can improve the living condition of people. To make phone sets, the industry needs coltan, a mineral found only in a few spots of our planet. One of these is the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Since the request is high, coltan is valuable and attracts mining investors. Even during the civil strife that has gripped the DRC in the past two decades, coltan mining did not stop. Indeed, exploiters were more than ready to support the local guerrillas to have access to the mineral; to the detriment of the local population. Workers in these mines are paid a pittance, experience insecurity for themselves and their families, and have no real expectation beyond the near future, only to give manufacturers the opportunity to get richer. How many people would feel comfortable to use a mobile phone if they knew that this technology contributes to the poverty and enslavement of others? Would they not accept to pay more to give those people a better life?

While I am writing this article, an off-shore oil well in the Gulf of Mexico is pouring millions of barrels of oil in the sea. It is the worst environmental disaster ever. Millions of people – fishermen, tourism industry workers – have lost their source of livelihood; millions more will not be able to enjoy the environment where they live; sea life has been destroyed and it will take decades before things go back to normal. All these happened for the hunger of more oil to feed our development system.

New models of development

It is clear that industrialization, especially the present model of industrialization, is not the answer to bring development. People realize that we need to change. We need to develop new sources of energy and ways of having energy for our daily life while respecting the environment. We need to accept that some resources should not be exploited, because there is the greater risk to harm the environment, and so lower our quality of life. We will need to make sure that local communities benefit from the resources they have and we need. Renewing our model of development will prove difficult. A more just sharing of resources will mean that the rich West will have to lower its standards, and participate in supporting the growth of the South. It will also mean a growth in environmental awareness and renouncing certain privileges. All these choices are personal choices, but they are also political ones. The faith community has a duty to help design new development models so that they safeguard the integrity of creation. Supporting new models of development is a political decision, and an important one. The reflection about how we want to run the world in future needs constant checking with the will of God. Whenever we take a decision of importance without God within the horizon, we tend to favor the interest of a few. The Church needs to be involved in these decisions, encouraging people to search for ways considering the well-being of all, in respect of God’s will.

The human being is not just a matter of food and drink alone. There is much more to a person than living, even a comfortable life. The person has great potentials: to create beauty, to love, to build harmonious families and societies. This is possible only if the person has an integral formation. This kind of formation is a political action. In fact, integral growth touches upon all aspects of human life. A person who has received the tools to grow, in body and spirit, is also asked to take a responsible place in society. Faith-based community, and the Church, in particular, have a duty to address people and offer them such tools. It is not by chance that dictators impose a syllabus in state controlled schools, and do not like the Church to offer alternative formation. They know that shaping the knowledge and expectations of people is a prerequisite to control society. By its very nature, the Church may help in this process of integral formation offering people a chance to realize their duties and rights, to discover the relationship with their human fellows and God, to taste the importance of family life, social commitment and shared interest in others.

Geared to communion

We have seen that the Church must be involved in political life. We have also highlighted the foundation of this commitment. The aim remains one: to help people build a just society, living fulfilled lives. This means that the Church supports all journeys that bring people together and favor communion with God. The tools to shape political life are well known: forming people and their leaders, taking a prophetic role, and encouraging personal commitment. There is no good political life without formation. This is not for leaders alone; all should strive to have the basic knowledge of political living. There is no good choice if the mind has not been informed properly. The first step is to help the grassroots to become aware of their rights and duties, to aid them in identifying the root causes of the issues that need to be resolved, and to support the search for solutions. This process empowers a local community to face reality and take action. Leaders should also be prepared not only to listen to the people, but to actively seek for their opinions. A good leader is one who is capable of walking with the people. He might see ahead, yet he strives to reach the goal together with others. When the Church offers leadership workshops, accompanies university students in their integral formation, addresses politicians offering them important insights, then the Church facilitates the policy-making process, and this is good politics.

However, there are cases where the Church cannot simply support and advise. When facing situations of injustice, the Church must have the courage to take a stand. This is the real meaning of the prophetic role of the Church: the ability to read the signs of the times and proclaim the truth, even when this goes against the political order of the day. In recent times, many Christians have given their lives to defend the truth or to compel a change in society for the common good. One example is Oscar Romero, whose 30th anniversary of martyrdom, we remember this year.

Taking a stand for the truth

Once he told a friend: “Every person has his roots. Mine are that of a poor family. I suffered hunger, and I know what it means to work when you are a child. Eventually, I went to the seminary. From then on, I spent most of my life with books. I was sent to Rome to study until I forgot my origins, I was living in a new world. When I came back, I became the secretary of the bishop. Twenty-three years immersed in more papers. I was then sent to San Salvador as auxiliary bishop. There, I fell in the hands of Opus Dei, and there I was trapped … Later, I was sent to Santiago de Maria, where I faced again the poverty of the people; children dying because they had to drink dirty water; farmers working hard for hours on end. At that time, I was like a spent coal; a wisp of wind was enough to ignite a fire again! And a great fire it was when Fr. Rutilio Grande was killed because of his commitment. I thought it was time to follow his footsteps. I changed, it is true, but I like to think of it as a coming back! I have received death threats. As a Christian, I do not believe in death without resurrection. If they kill me, I shall rise again in the Salvadorian people. My death, if God wills it, will be for the liberation of my people and a witness for the future. A bishop will die, but the Church – that is the people – will never die.” He never looked for martyrdom, but he did not run away from it either, preferring a commitment to justice than retreating to silence to live a quiet life.

Bishop Romero could have easily stepped back in the shadow, waiting for the civil war to pass, asking his faithful to be prudent. But he chose to speak up for the truth. He did not take sides; he did not support one group against the other. He simply asked for justice for his people, especially the poorest. Romero has become an important figure for the Church in Latin America, a witness of the Gospel recognized by Christians around the world. His public cry for justice was rooted in the Word of God. When he spoke, he spoke as a bishop, as the guide of a people suffering injustice. Politicians accused him of being a leftist, of siding with rebels. In reality, Bishop Romero did not pay much attention to party politics but focused on policies. He expected politicians to serve their people and to act according to the ethics proposed by the Gospel. He was not the only Catholic to stand up against injustice and violence. Romero saw many of his priests assassinated for their stand on justice issues: Rutilio Grande, Alfonso Navarro, Ernesto Barrera, Octavio Ortiz, Rafael Palacio, and Napoleon Macias. Many also were lay people who lost their lives supporting the cause of a new social structure for El Salvador.

Along with many other people of faith, Romero understood the importance of taking a stand for the truth. He did not look for a place in the sun. He wished to serve his people. He was ready to work with anyone interested in the good of all, and did not refuse to talk even with the tyrant of the day. He and the many freedom martyrs showed us what political commitment of the Church, at the service of truth, and care for the people, in the light of God’s will, means.