Last October 29, the long life of Archbishop Emeritus Henry Karlen came to a conclusion at the age of 90 in Zimbabwe, his country of adoption. Thousands of Catholics attended his funeral in Bulawayo. Known as the “Father of Bulawayo Diocese” for his work of building the church in Matabeleland, he was laid to rest at Athlone cemetery. Three cabinet ministers joined the many mourners who also included bishops from other churches.

The three ministers were Mzila, Moyo and Coltard, who had been particularly close to Archbishop Karlen as a witness of the Gukurahundi massacres. Mzila, a liberation war veteran who was jailed by the Rhodesian administration, was arrested last year for attending a memorial service for the victims of the 1980s massacres. As a child, Moyo watched one of Mugabe’s inner circle burn down his parents’ home. Education Minister Coltart, a lawyer by profession, was a director of the operational arm of the Legal Resources Foundation in Bulawayo and one of the main movers and authors of the “Breaking the Silence” report about the massacres.

The provincial superior of the Marian Hill Missionaries, Fr. Peter Nkomazana, said, during the funeral, that the Catholic Church in Zimbabwe had lost one of its longest–serving leaders. He said that Archbishop Karlen had been passionate about the Gukurahundi atrocities perpetrated by the people in power at that time, atrocities that he had disclosed to the world. This is why, even in his last days, he still said that he could not understand why Africans were killing each other. Moreover, till the last days, he had again passionately cared for the livelihood of the poor and for the people living with HIV and AIDS.

Unsurprisingly absent from the funeral was President Robert Mugabe, the more than octogenarian former freedom fighter, still in power after more than thirty years, who had defined Archbishop Karlen as “the sanctimonious prelate” at the time of the disclosure of the massacres.

Troublesome Way To Independence

In the 20th–century, the sixties saw the coming of age of black Africa with the declaration of independence of the majority of its countries. Some were handed independence on a golden platter by the colonial powers, like Uganda, where transition to independence from the British rule happened peacefully. Some fought bloody guerilla wars for it like Kenya, with the Mau Mau rebellion. Generally, it was the presence of white settlers that made the passage difficult and slow, given the vested interests of the powerful minority. That was the case of Zimbabwe.

The nation of Zimbabwe, formerly the British colony of Rhodesia, is a landlocked country in southern Africa, bordered by Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa and Zambia. In 1965, the colony’s white minority refused the British plan of black majority rule as a requirement for independence and unilaterally declared Rhodesia independent. World opinion and a prolonged civil war forced Rhodesia’s white dominated government to accept a limited form of black majority rule in 1979.

Guerilla attacks, however, continued until late that year, when negotiations under British auspices led to a cease–fire and the restoration of British rule over the breakaway colony until new elections, that included all groups, could be held. In 1980, Rhodesia gained full legal independence under black majority rule, with Robert Mugabe as president and changed the name to Zimbabwe. The Catholic bishops of Zimbabwe had supported the struggle for independence of Mugabe and all the other leaders of the black majority.

Terrorized, Starved And Butchered

The new government was in the hands of the major tribe, the Shona, and of Robert Mugabe, the leader of ZANU. The other large tribe, the Ntebele, was under the movement of Joshua Nkomo, ZAPU, intending to run a democratic opposition. Three years after independence, reports filtered in to Bishop Henry Karlen of Bulawayo from colleagues at rural churches, hospitals and mission stations, in the two Matabeleland provinces, about the slaughter of opposition supporters loyal to leader Joshua Nkomo, widely known at that time as “Father Zimbabwe.”

Bishop Karlen had learnt that a new, North Korean–trained brigade was ordered into Matabeleland by Mugabe. Shaken but courageous Catholic clergy, and mission hospital staff at St Luke’s, reported to Bishop Karlen about this new war which was, in many ways, even more devastating than the war to end white rule.

He made notes of what he was told and his ghastly file grew with each harrowing account. Bishop Karlen presumed that Mugabe did not know about it and that, if he did know, he would stop it. So he tried to contact Mugabe, but his calls were not returned. In anguish, he decided, in February 1983, to call Garfield Todd, the former Rhodesian prime minister.

Todd had many close friends and colleagues in the new Zimbabwe government. He was reviled by most whites, and his movements were restricted by Ian Smith, leader of the white minority government during the civil war, but Todd, the man who had a non–racial vision for Rhodesia, was honored by Mugabe after independence and made a senator.

Bishop Karlen told Todd that the state was perpetrating atrocities, that people were being terrorized, starved and butchered, and their property destroyed. He asked Todd to secure an appointment for him with Mugabe. Todd was aghast at what he heard. At Todd’s request, the Bishop sent his file to Todd’s daughter, Judith, in the capital, Harare, who read it and forwarded it to senior members of Mugabe’s government.

In March 1983, Bishop Karlen and Mike Auret, director of the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace, met Mugabe for several hours ahead of the Bishop’s Conference and handed him a report largely based on the Bishop’s notes. In his report to Mugabe on the atrocities, Bishop Karlen wrote: “Your own soldiers are saying: “We are sent by Mugabe to kill.” Then, the Zimbabwe Catholic Episcopal Conference issued a strongly worded pastoral letter by the title; “Peace is still possible,” which estimated that thousands had been killed.

This was a difficult moment for the bishops. Some senior Catholic clergy had opposed white minority rule, and came to know and respect Mugabe when he went into exile in Mozambique to become president of ZANU, and commander of its military wing. Bishop Karlen and his colleagues had celebrated when the civil war ended and went out of their way to support the new government. The shock of learning about state-ordered massacres and the torture of Nkomo’s supporters profoundly affected Bishop Karlen and his fellow bishops.

A “Moment Of Madness”

News of the atrocities broke in The Star and other newspapers of its group in South Africa and in The Guardian in London later in 1983. With increasing domestic and international outrage at what many believed was a genocide against Nkomo’s supporters, and following the statement by the Zimbabwe’s Bishops Conference, Mugabe retaliated by issuing the words “sanctimonious prelates” to describe Bishop Karlen and his colleagues.

But he did appoint a commission of inquiry into the deaths, estimated by Mugabe’s officials at 1,500 people. The commission was chaired by Harare lawyer, Simplicius Chihambakwe, still in practice in Harare. Bishop Karlen was relieved that the commission had been formed and went to give evidence, using the mass of information he had collected.

The commission completed its work in 1984, but Mugabe withheld its findings. The Legal Resources Foundation, a non–governmental organization, went to court seeking its release, but its application was refused. With no public document available, the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace and the Legal Resources Foundation began a long and difficult investigation into the appalling events in Matabeleland, and the origins of the enmity between Mugabe’s wartime forces and those loyal to Nkomo.

Bishop Karlen’s file and his memory were a starting point for the investigators. Mugabe’s intelligence agents hindered their work at every level, and the investigators were also hampered by lack of resources and fear among survivors about coming forward to give information. And many witnesses to the horrors had fled to South Africa during the height of the slaughter.

Eventually, the two organizations produced a long, detailed report called: “Breaking the Silence – Building True Peace,” which estimated that about 20 thousand people had been killed in Matabeleland and in parts of the Midlands province from late 1982 until Nkomo, by then exhausted, went into an inclusive government with Mugabe in 1987.

When Auret released the report in 1997, only Bishop Karlen and a second bishop endorsed its publication for general distribution. For the rest of his life, Bishop Karlen, who became archbishop in 1994, would say he could never understand why the new government chose to murder its citizens.

Mugabe described the Gukurahundi killings as “a moment of madness,” but 20 years after they ended, victims are yet to receive any compensation. In 2001, Mugabe revoked Todd Garfield’s Zimbabwe citizenship as a punishment for helping Bishop Karlen in denouncing the Gukurahundi massacres.

The Good Shepherd

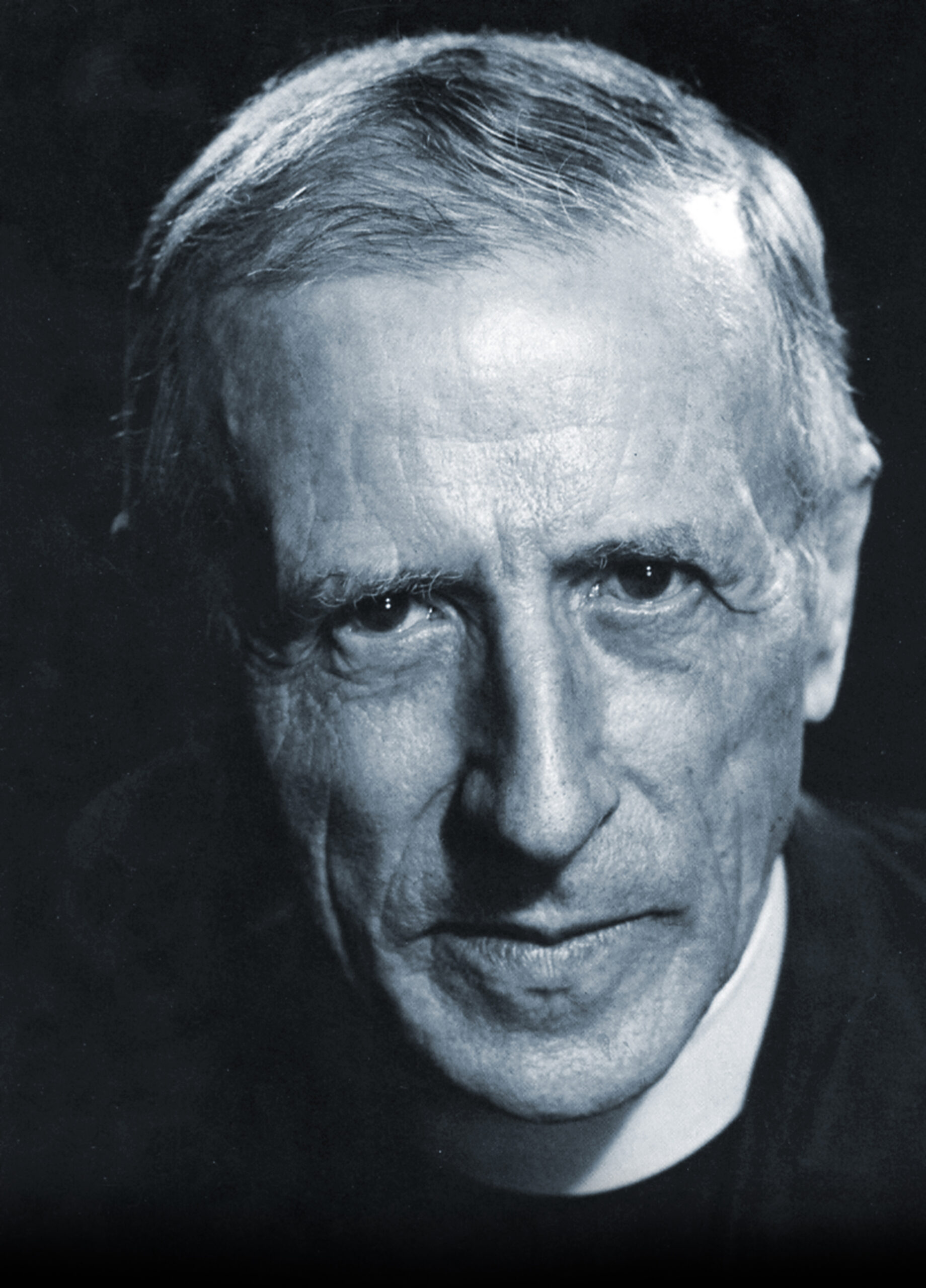

Archbishop Henry Karlen was born in Torbel, Switzerland, on February 1, 1922, to Victor and Victorina Karlen. Henry joined the Marian Hill Missionaries at the age of 20 in 1942. He made his perpetual profession in 1946 and was ordained to priesthood on June 22, 1947 in Switzerland. He got his doctorate in Theology in 1950. In 1951, he was assigned to Africa. His first post was at St. Peters Seminary in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa, where he lectured on Moral Theology and Canon Law. His first appointment as a parish priest was in 1959 at Qhumbu Mission, Umtata. This lasted until 1963 when he was appointed the administrator of the Cathedral in Umtata.

In September 1968, he got his papal appointment by Paul VI to the Order of Bishops. On December 12, the same year, he was consecrated as the Bishop of Umtata Diocese. In 1974, in May, he was informed of his new appointment as the Bishop of Bulawayo. Thus, he arrived in Bulawayo, the second capital city of Zimbabwe, destined to be his city in life and in death and his final resting place here on earth. His enthronement was on August 15, 1974. In 1994, he was appointed Metropolitan Archbishop, thus, receiving the pallium as archbishop from the then Apostolic Nuncio Peter Prabhu at St. Mary’s Cathedral.

We can regard him as the good shepherd of Bulawayo Diocese because he built it up in so many aspects. He printed the Ndebele Sacramentary, the lectionary, the adult and children’s catechism and promoted the active participation of the laity. In 1979, he was the first bishop to ordain permanent married deacons: 9 men were ordained to the Order of Diaconate. This was a courageous, even prophetic, gesture since, only in other very rare cases, married people have been ordained as permanent deacons in Africa.

He opened four town parishes and as many mission stations. He instituted the annual pilgrimages to Empandeni Marian Shrine. Emthonjeni Pastoral Centre was his brain child so as to empower the pastoral workers in the diocese. During the civil war in 1970’s and the disturbances in the 1980’s, Bishop Karlen was untiring in his courage to reach the people most affected by the violence. He retired as Archbishop of Bulawayo in 1998.

He wrote the book, “The Way of the Cross of a Diocese,’ to chronicle the murders of missionaries and civilians and what he had done to bring comfort to the families, and recognition of these happenings to the international community. Among his other writings, we have: “The Spirituality of Marriage,” “On Death and Dying” and “Towards a Self–supporting Church.” In 2007, at a public gathering in the large City Hall, he was conferred a Civic Award “Freedom of the City of Bulawayo” by the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) of the city government, then still in opposition to Mugabe, later in uneasy alliance.

Archbishop Karlen was the quintessential missionary and pastor who joined his life inextricably to the destiny of the people he served. A clever and well read priest, he excelled in all the jobs he was entrusted with: in teaching, in administration but especially in paying attention to the needs of the persons he served. To a superficial observer, he may have appeared as a person who was profoundly let down by those he had put his trust in.

This happened, in civil life, in a tragic way, when he was forced to witness the betrayal of the black people of Zimbabwe by the very leaders who had brought them to independence. This seemed true also, in church life, when the one who had stood by him during the time of denouncing the massacres and had later succeeded him as bishop of Bulawayo, Pius Ncube, was forced to resign not long ago after a government–sponsored operation allegedly caught him having an affair with a married parishioner.

But the elderly missionary did not succumb to pessimism or cynicism as far as the people he had chosen to serve were concerned. He certainly knew the weight of cultural heritage that cannot be changed easily or quickly. He stayed and trusted. With this trust in God’s long–term plan, he peacefully closed his tired eyes to this world.