The spiritual and historical link between 1521 and 1565 is the icon of the Santo Niño. This iconic gift of Ferdinand Magellan–his Portuguese name is Fernão de Magalhães – so symbolic of the seed of Christianity planted in these islands, was lost in 1521. But it was found or discovered (Kaplag in Cebuano) by a Spanish soldier 44 years later. In between those years, the same seed of the Christian faith has been silently growing in the hearts of the native Cebuanos.

In the first place, why is this discovery so significant? The reason is plain and simple— no kaplag of the sacred image in 1565 simply means no Santo Niño devotion today, a devotion that makes God’s loving presence in our archipelago more alive! Hala bira! Five solid centuries after, devotees still feel the deep impact of that discovery as they join and enjoy the Sinulog—the Santo Niño festivities held on the third Sunday of January in Cebu— and Dinagyang in Iloilo City. Both are said to be adaptations of the Kalibo’s Ati-Atihan Festival, known as “The Mother of all Filipino festivals.”

Now, it is good to go back to the historical origin of this most festive devotion. When historical dates were being contested, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP), after consultations with ace historians and experts, specified two events in 1521 as dates of reckoning of the 500 Years of Christianity (YOC) in the Philippines. One is the first Mass celebrated in the island of Limasawa on March 31, 1521 (Easter Sunday), and the other is the first baptism in Cebu on April 14, 1521. CBCP tells us that these dates are key points of historical reference in Philippine history.

Fray Pedro de Valderrama, Magellan, and his men celebrated the first Mass in Leyte. From there, they reached the island of Sugbu (the former name of Cebu), where Magellan instructed his soldiers to plant a large wooden cross. Fray Valderrama was the Andalusian capellan (chaplain) of the fleet, and the one and only Catholic priest in Magellan’s crew.

Magellan’s Italian chronicler and scholar Antonio Pigafetta jotted down one detail in Philippine history: “After the cross was erected in position, each of us repeated one Our Father and one Hail Mary, and adored the cross…” (Pigafetta, Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo, 1529).

THE FIRST BAPTISM

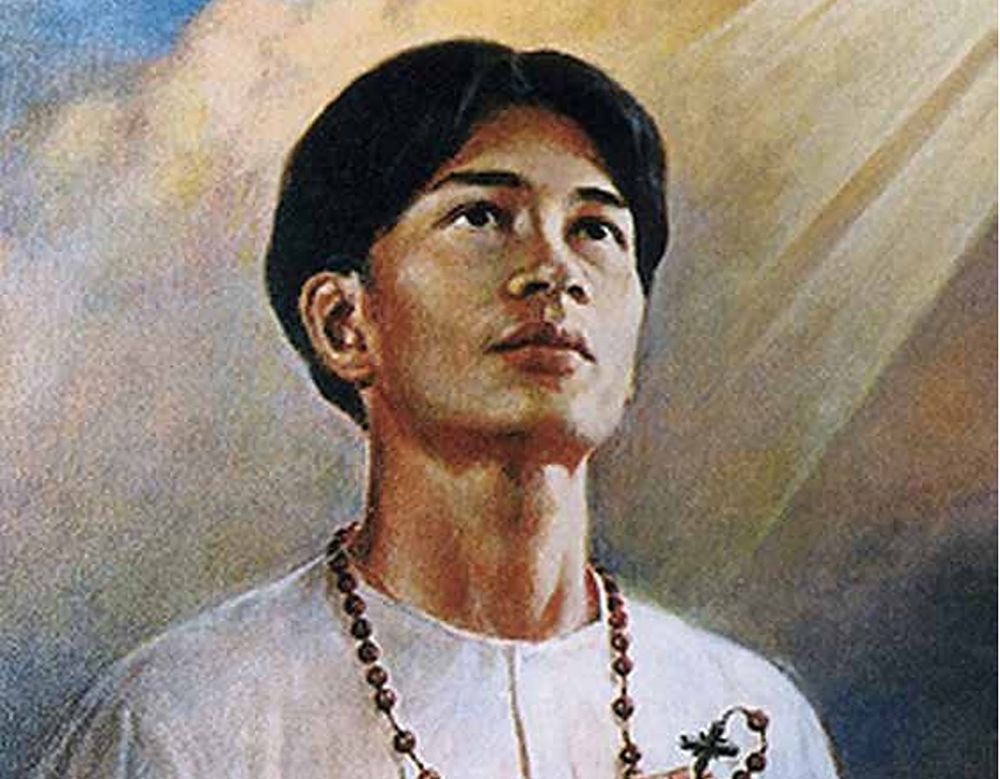

The full heat of summer was upon them when the local ruler, Rajah Humabon, and the autochthonous people of Cebu were gathered together to hear the good news of salvation for the first time, a fulfillment of the mandate received from Christ: “Go into all the world and preach the gospel, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 28:19).

The Portuguese explorer Fray Valderrama had the honor of explaining to the natives the age-old Catechism of the Catholic Church. In those days, on this blessed island of Cebu, Magellan was the messenger, and his Malaccan slave, Enrique, was the translator. Pigafetta left no doubt as to the pleasure that Magalhães derived from delivering his first “sermons” to the attentive audience. The Italian chronicler writes: “The captain said many things about peace… The people said they never heard such glad tidings and that they took great pleasure in hearing them…”

On April 14, 1521, after they heard the basic catechism of the Catholic faith, Rajah Humabon, his consorts, and subjects were baptized. Rajah Humabon was christened Carlos in honor of Charles V, who was both the King of Spain (1516-1556) and the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (1519- 1558).

Rajah Humabon’s chief consort, Hara Humamay, was given the name Juana after Charles’ mother, Joanna of Castile (1479-1555). She was known historically (post factum) as Juana la Loca, “Joanna the Mad,” who slept next to her husband’s corpse.

Antonio Pigafetta gave us a firsthand narrative of the event of the historic mass baptism in 1521: “We were baptizing eight hundred souls among men, women, and children. The queen was young and beautiful, all covered with a black and white cloth: her mouth and her nails were very red…”

THE GIFT

That day, Ferdinand Magellan presented to Hara Humamay an image of the Santo Niño, the miraculous image now considered to be the oldest Catholic relic in the Philippines.

The icon Magellan presented was a statue of a child carved in dark wood. It measured one foot tall and dressed in the Spanish royal fashion of the 16th century, consisting of a crown, a sash, a belt, and a long flowing cape. It depicts the Child Jesus with a serene countenance, wearing a predominantly red vestment with a long-sleeved shirt with lace ruffles and a gold-embroidered vest over a pair of trousers tucked into a pair of golden boots.

The Child holds a scepter in his right hand, raised in benediction. His left hand holds an orb with a cross, symbolizing two things: religious and political. The religious symbol refers to the dominion of God over all creation, and the political symbol refers to the sovereignty of Spain over a vast territory around the globe.

Spain was once “the empire on which the sun never sets.” The Spanish global empire was so vast that, as Earth revolves around the sun, at least one conquered territory was in daylight. In those days, the religious and the political were inseparable.

According to Pigafetta, Hara Humamay, upon seeing the icon of the Santo Niño, “was seized with contrition, and weeping, asked for baptism.” The generous gift to the queen was accompanied by a soft whisper—a friendly request to destroy all the idols and shrines that were associated with their past non-Christian practices.

Pigafetta proceeds in his chronicle to tell us how Rajah Humabon made a blood compact with Magellan and that, to seal their friendship, Rajah Humabon requested Magellan to kill his territorial nemesis, Lapu Lapu, who was the chieftain of nearby Mactan Island. Then the bad news followed. At the Battle of Mactan, today’s Punta Engaño, the warriors of Lapu Lapu maimed and killed Magellan, and his body was taken as a trophy.

Meanwhile, Rajah Humabon poisoned the remaining Spanish leaders of the expedition, Duarte Barbosa, João Serrão, and the other soldiers, during a festival in Cebu to which those soldiers were invited.

It was a tragedy. The first evangelizing attempt was a failure. It seems that the first Sacraments administered were lacking in adequate preparation. Catechesis was shallow and Baptism was rushed. The early natives who were baptized lapsed into their native worship after the death of Magellan. However, the memory of the face of the little Child Jesus probably lingered.

KAPLAG

Now, feel another episode of God writing straight with twists and turns in Philippine history. As I’ve indicated earlier, the spiritual and historical link between 1521 and 1565 is the icon of the Santo Niño. Forty-four years after the tragedy occurred, the expedition led by Miguel López de Legaspi, a Spanish contingent that included Fray Andrés de Urdaneta, OSA (1498-1568) and his pioneering Augustinian companions, arrived on February 13, 1565. Upon arrival, they encountered a very strong resistance from the natives, to which, for several weeks, the foreign soldiers bombarded and burned down the whole coastal town of Sugbu.

During the mapping operations on April 28, 1565, the Spanish soldier Juan de Camus, a sailor from Bermio, Vizcaya who served under Legazpi’s command, found (kaplag in Cebuano) the sacred image of the Santo Niño. Secured inside a Spanish crafted wooden box, the icon was wrapped with a white cloth. It was indeed the same image that Magellan gave Hara Humanay 44 years earlier! Legaspi and the Augustinian friars believed it was a miracle that the icon survived the massive destruction by fire and its recovery (kaplag) among the ashes.

Commander Legaspi shared his joy with the Spanish King in his report (relatio in Spanish): “This was kept in its cradle, all gilded, just as if it were brought from Spain: and only the little cross, which is generally placed upon the globe in his hands, was lacking. The image was well kept in that house, and many flowers were found before it, and no one knows for what object or purpose. The soldier bowed down before it with all reverence and wonder, and brought the image to the place where the other soldiers were” (Relatio, Julio de 1569).

No one can imagine Cebu without the Basilica Minore dedicated to Santo Niño. It is not even possible to think of Pandacan, Batangas City, Tacloban, Iloilo City, Kalibo, or Tondo, Ternate, or even the entire Philippine archipelago, de Aparri hasta Jolo, without the Santo Niño.