TAKASHI NAGAI: THE MYSTERY OF ATONEMENT

In the morning of August 9, 1945, Dr. Takashi Nagai was working in his office at the medical center in Nagasaki, Japan. At 11 a.m., he saw a flash of blinding light, followed by darkness and a crashing roar. At that moment, his world collapsed around him. It was the explosion of the second plutonium-fuelled atomic bomb five hundred yards over the Urakami Cathedral of Nagasaki. The first, a little time before, had fallen over the town of Hiroshima.

After escaping from the rubble and receiving treatment for a severed carotid artery, Nagai saw that his children had survived, but he had to gather to himself the small heap of ashes that remained of his wife, Maria Midori Nagai, together with her rosary beads, surprisingly intact. He then joined the rest of the hospital staff in treating the survivors. Given the force and heat of the blast, he imagined that such a big bomb must have killed hundreds of people. Only, gradually, did the extent of the destruction become clear. The bomb had killed nearly 80,000 persons, and wounded many more.

As Robert Ellsberg writes in his profile “The Mystic of Nagasaki,” Nagai witnessed scenes of horrifying suffering. The intense heat near the epicenter of the blast had vaporized humans, leaving only the outline of their shadows. Hordes of blackened survivors, the skin hanging from their arms, desperately wandered the streets crying for water.

Such circumstances might naturally prompt a range of reactions – madness, despair, or the hunger for revenge. But in the days following the explosion, Nagai, a devout Catholic, instead expressed a most unexpected attitude – namely, gratitude to God that his Catholic city had been chosen to atone for the sins of humanity.”

In arriving at this perspective, Nagai undoubtedly responded with the strong consciousness of Nagasaki’s Christian population. Since the time of the early Jesuit missions, the city had been the center of Japanese Catholicism, and consequently, the scene of extensive martyrdom. Over time, Japanese Catholics had claimed a deep identification with the cross of Christ and a conviction that atonement must come only at the price of blood.

Thus, it seemed natural for Nagai to pose the question: “Was not Nagasaki the chosen victim, the lamb without blemish, slain as a whole burned offering on an altar of sacrifice, atoning for the sins of all the nations during World War II?”

THE SUFFERING, ATONING CHRIST

The same perspective inspired the scene of Jesus speaking to the imprisoned missionary in the novel “Silence” (1966) of Sushaku Endo. Jesus appears not as the beautiful, haloed and serene Christ of the missionary’s devotions, but the Christ of the twisted and dented fumie (the images of the face of Jesus used by the persecutors to force the Christians to step on), the trampled upon, and suffering Christ. And what the Christ says to the priest shocks him to the marrow: “Trample on me, trample…It was to be trampled upon by men that I was born into the world; it was to share men’s pain that I carried My cross.”

Nagai found it remarkable that the bomb had been dropped that day on Nagasaki, as a result of heavy clouds obscuring the originally intended city. As a further result of clouds, the pilot had not fixed his target on the Mitsubishi iron works, as intended, but instead on the Catholic cathedral of the Urakami district of the city, home to the majority of Nagasaki’s Catholics. Moreover, he noted that the end of the war came on August 15, the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, to whom the Cathedral was dedicated. All this was deeply meaningful. “We must ask if this convergence of events – the ending of the war and the celebration of her feast – was merely coincidental or if there was here some mysterious providence of God.”

Dr. Paul Takashi Nagai, himself a victim of the atomic bomb, became its mystic: he gave his life to the mission of making Christian sense to the greatest war tragedy of modern history. He was himself a convert. Born on January 3, 1908, he had become a Catholic in 1934. His conversion was prompted by several influences, especially the example of his fiancée, who belonged to an ancient Catholic family. Nagai pursued a career in medicine, ultimately entering the field of radiology. In 1941, he suffered from incurable leukemia, induced by his exposure to x-rays. Nevertheless, he was able to continue his work, and in 1945, he had become the head of radiology at the University of Nagasaki.

The effects of radiation, combined with his previous illness, left Nagai an invalid, barely able to leave his bed. He lived as a contemplative in a small hut near the cathedral ruins in Urakami, writing books and receiving visitors. Increasingly, he came to believe that Nagasaki had been chosen not only to atone for the sins of the war, but also to bear witness to the cause of international peace. Dr. Takashi Nagai described his experience of the atomic bombing and the aftermath in his bestseller book, “The Bells of Nagasaki” (1951). He died on May 1, 1951, at the age of forty three.

AGNETA CHANG: THE TIP OF THE ICEBERG

Agneta Chang, a Korean Religious Sister and a woman of outstanding personality, refused to abandon her people and save herself. She is like the luminous tip of the immense iceberg representing the masses of the Christian suffering humanity who have disappeared un-named in the underground maze of history.

Sr. Mary Agneta Chang came from a Korean family which had been Catholic from the time of persecution in the 19th century and which included at least one martyr among her mother’s ancestors. Hers was a well-to-do family.

Her father provided education in the United States for two of his daughters as well as his sons. Her brother, John Chang, served as delegate to the United Nations, Ambassador to the United States and also, shortly, as Vice-President and Prime Minister of the Republic of Korea. The whole family had a special friendship with the Maryknoll congregation which they came to know and appreciate both in the States and in Korea.

Agneta joined the Maryknoll Sisters while studying in the States. She was assigned to Korea in 1925, after completing novitiate training at Maryknoll, New York. She did parish and catechetical work in Uyju and taught Korean language to her American companions. She had natural gifts for art and music, sewing and embroidery, and became proficient in English. She was attracted to the Scriptures and contemplative saints and authors. After five years in Uyju, she went to Japan, to the College of the Religious of the Sacred Heart, for further study, obtaining an A.B. degree in 1935.

The Korean community of the Sisters of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, a local congregation, was started in the Diocese of Pyongyang in 1931. Four American Sisters were involved in the formation of this young group and Sr. Agneta joined them upon the completion of her studies. She remained with this community, right across two wars.

UNDER COMMUNIST YOKE

In 1941, the war broke out between Japan, which had annexed Korea early in the 20th century, and the United States. It was then that the American Sisters were repatriated and Sr. Agneta was left alone to continue the work as novice mistress on behalf of the young community of Korean Sisters. During these years of war and Japanese domination, she found herself cut off from her Maryknoll headquarters and in charge of 29 women with insufficient funds, in a time of food shortages and high inflation.

For a short time between the surrender of the Japanese to the Americans in Seoul in 1945 and late in 1948, she again had contact with the motherhouse in the U.S., receiving letters and supplies through her family in Seoul. But, in that year, with the departure of the Russian troops that had entered North Korea during World War II, the Korean communists took control of the country.

The Sisters, middle-class and educated, attracted their enmity and experienced their more intensive use of investigations, inspections and residence checks. Sr. Agneta, because of her American ties and her brother John’s position as diplomat, attracted special suspicion. She decided not to risk appearing in public. Soon, the last building used by the Perpetual Help Sisters was taken over by the government, and each Sister, dressed in lay clothes, left for home. At that time, many priests and even bishops were arrested and killed.

BURIED IN A MASS GRAVE

Sr. Agneta’s health was poor since she previously had back surgery. Sr. Peter Kang accompanied her as she took refuge in various villages, the last being in Songrimri, about 25 miles from Pyongyang. The Korean war had, in the meantime, broken out and by October 1950, the United Nations forces began to drive northward, reaching the 38th parallel, putting pressure on the communist North.

On October 4, 1950, a representative of the Communist military mobilization office came for Sr. Agneta, demanding that she help care for wounded soldiers. Sr. Peter pleaded in vain that Sr. Agneta was ill and unable to walk. Neighbors were forced to help load her bed on a waiting ox-cart. Sr. Peter tried to follow but was turned away. She, with a handful of other Sisters, eventually headed for the south – to freedom.

This is how she describes the moment of separation: “The time was about eight in the evening. The world was wrapped in dusk. The only sound was that of the ox-cart jogging down the mountain trail together with the groaning and the sound of Sr. Agneta’s prayers. She made no complain but only exclaimed: ‘Lord, have mercy on us! O miserable night! My heart seems to shatter and break into a thousand pieces at the thought of it.’”

That was the last moment that Sr. Agneta was seen alive. Sr. Agneta’s final moments remain unknown, but a group of women were said to have been executed and hastily buried in a mass grave. The site was never located.

SHIGETO OSHIDA: WHEN BUDDHA MEETS CHRIST

World War II is raging in the Far East. The Japanese army has invaded the surrounding countries: Singapore, Southern China, Thailand, the Philippines. Everywhere the cruelty and fanaticism of the Japanese soldiers had spread terror and the grim fate of the people in their prison camps will remain in the collective imagination and be the object of famous films like “The Bridge Over the River Kwai” by David Lean or novels like “King Rat” by James Clavel.

It is against this somber background that God performed a tiny, personal miracle that transformed the life of a young Japanese man in his twenties, a simple, humble follower of the tradition of Zen Buddhism, Shigeto Oshida.

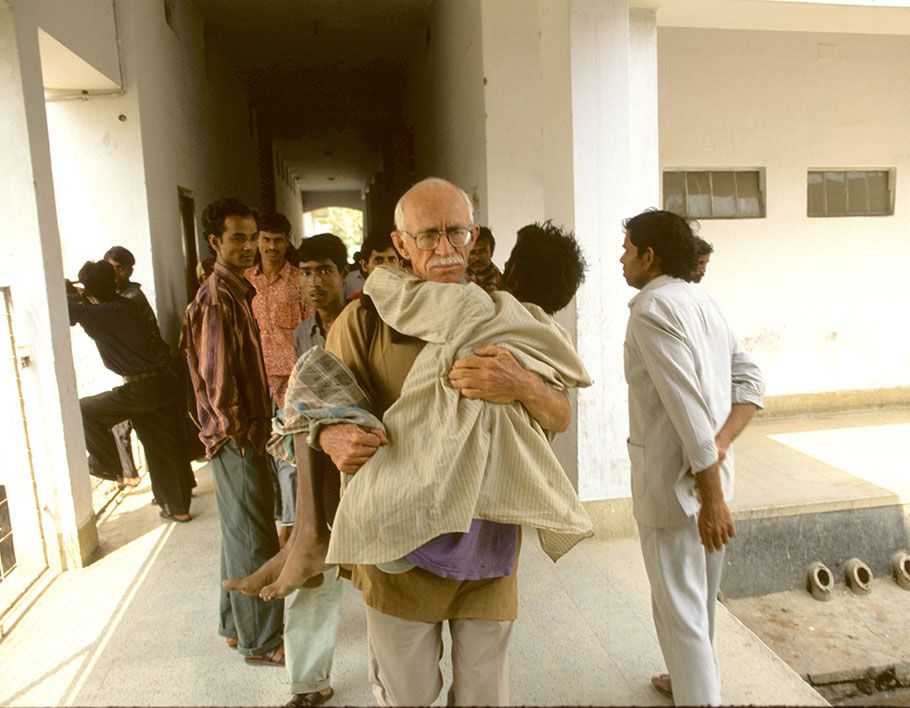

Years later, Fr. Oshida would mention many times the circumstances of his encounter with a German Catholic youth who was instrumental to him meeting Christ: “As soon as I saw that Christian man I already believed. I did not yet know the dogmas, but I already believed. I had no problem in accepting the dogmas because I first believed in the testimony of a true Christian.”

How transparent must have been the goodness of Christ in the face of that youth! Fr. Oshida used to talk at length of his journey as a young man into Zen and how, going through the dignified silence of Zen, he immediately believed in the Man who died on the cross pleading for universal forgiveness. “Forgiveness is silence within silence. Christ is the heart of Zen.”

Fr. Vincent Shigeto Oshida, OP, was born in Japan in 1922. After becoming a Christian, the young Oshida felt the desire to dedicate his life to Christ as a religious, and was attracted to the Dominican Order. But he fell sick with TB and was confined in a sanatorium. It was there that a small community was born around him, made up of his fellow patients who liked to pray with him and sit with him in Zen meditation. He already had the feeling that living and thinking in a Dominican monastery was not going to be natural to him. For the Wisdom tradition is to be simple with ourselves in order to be open to God. On that occasion, however, Jesus did not give him a clear answer, so he continued in his vocation.

He was sent to Canada to study theology. Upon his return to Japan, he was hospitalized once more for tuberculosis and had surgery which removed half of his right lung. He was then transferred to a sanatorium for convalescence in the district where he later settled. There, in the sanatorium, a small community of silence and prayer was born for a second time.

After approximately thirteen years of relative silence, he decided to talk with his local superior and was given the green light. At last, Fr. Oshida left the convent and created a small hermitage, where he and those who joined him lived in solidarity with their neighbors and practiced a way of life made up of manual labor, prolonged Zen meditation and a Christian liturgy of luminous simplicity.

THE GRASS HERMITAGE

It was 1964 when Fr. Oshida, then 42 years old, opened the hermitage Sooan in order to make room for all those who were attracted by his way of life (Soo means grass, an means hermitage). Sooan was in the village of Takamori, in the province of Nogano, not far from the sacred mountain Fuji. It was built like a traditional peasant hut. Takamori’s hermitage was neither an organization nor an institution. It was a humble place that fitted naturally in the ricefields, the streams and the rural life of the surrounding villages.

God gave Fr. Oshida forty years to stay in the silence and simplicity of Sooan and to pursue his search for Christ’s face and his listening to simplicity. God works through our simplicity. Simplicity can be like a “sacrament.” In the Christian tradition, a sacrament is a visible sign pointing to the presence of invisible grace. In Zen, it is precisely the simple and everyday things that have a sacramental character. There is nothing special about drinking tea, meeting people, going about one’s daily work, playing with children, or taking delight in nature; but it is in the elements of ordinary life that the mystery of existence opens up.

It is this simplicity that people sought in Fr. Oshida and that he took with him when he went out to preach at retreats, even to the Bishops of Asia, or hid in the pages of the many books he wrote. One day he received a visit from a Buddhist nun. He saw her standing at the door of the community grass hut. “I feel like I have come back home,” she said. Next morning she assisted at the Mass. After Mass she remained in the chapel. One of the Sisters was also there. After a while, she approached the Sister and said: “In Buddhism we have what we call ‘unifying communication’ between Buddha and ourselves, but in your place, the Hand of God appears visibly before our eyes.” Tears continued to flow down her cheeks. Some months later, Fr. Oshida received a telephone call from her telling him of a dream in which she was being baptized. Her official position at that time was one of those presiding at a temple near Osaka.

AUTUMN LEAVES AND RICE GRAINS

In the convent of Takamori, in the last days of his life, Fr. Oshida spent a long time contemplating the way autumn dresses the surrounding hills in colors. Looking at the leaves falling gently on the ground, he uttered the words that will remain on his lips until the last breath: “God is marvelous! Amen, Amen!” He left this world in a state of profound quiet, crossing to the other side of life while resting in a deep sleep. His face in death was radiant with beauty and peace. It was November 6, 2003.

Fr. Oshida was buried on the fifth day after his death by his followers and friends: the simple, wooden coffin was placed in the midst of the trees of the Sacred Memorial Wood that commemorates the victims of all conflicts.

After a prayer vigil that lasted throughout the night, the Mass was celebrated among the trees, near the small spring, and then the coffin was lowered into the earth, just behind the chapel of the hermitage, in front of the statue of Mary holding the Child Jesus. Some grains of rice were placed inside the coffin and then the tomb and the ground around it were strewn with beautiful autumn leaves: red, yellow, golden…These simple gestures in the celebration fittingly made present the religious figure of Fr. Oshida.

For the last forty years of his life, Fr. Oshida lived in his “Grass Hermitage,” searching for the face of Christ through the Japanese Zen Way that he had practiced in his youth. He became a point of reference in the dialogue between religions which he preferred to describe as “meeting in the depths.” In him, the wisdom of Asia became a heritage of the Church.