What are the differences between the Economy of Communion and other forms of economy, such as the social, solidarity economy? As an alternative to the hegemonic model, what are the characteristics of the Economy of Communion?

One difference, for example, about the solidarity economy model is that although it is born out of an essentially Marxist-type paradigm focused on the person, unintentionally, does not discuss the system of production, that is, normal economic relations. It deals with people who are out of the system, the marginalized, the excluded, but in so doing it does not call into question the economic relations of the capitalist system.

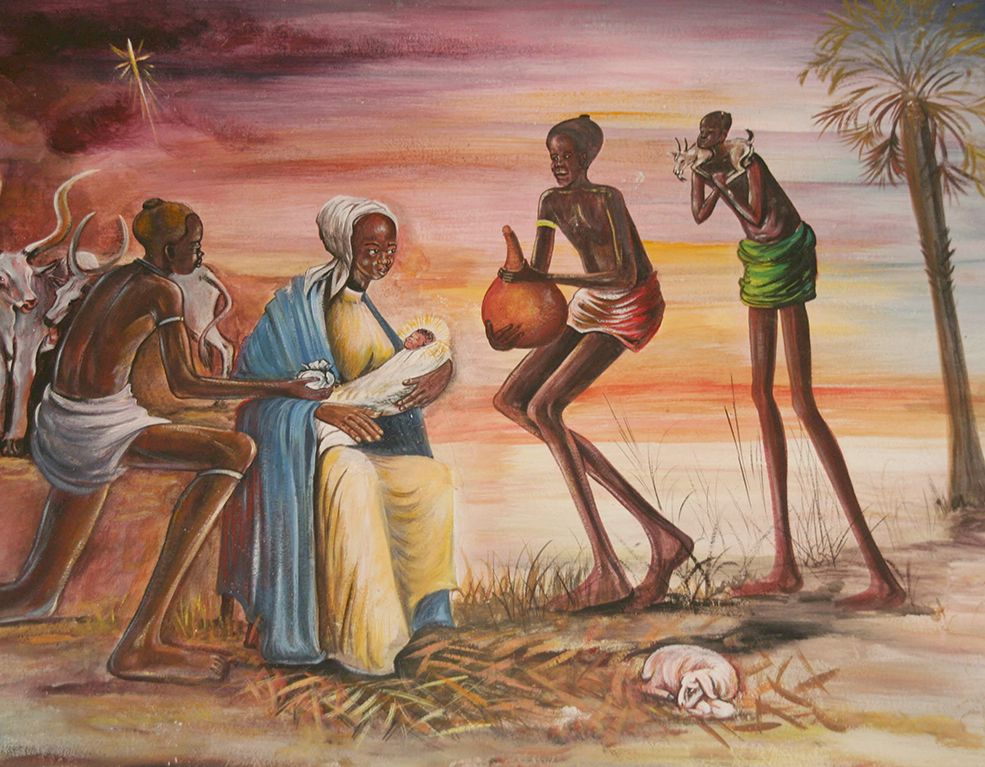

The Economy of Communion, by putting the company at the center, is saying that the company must change. In this way, it is not so much just to take care of the poor without changing economic structures, but to propose different, nonprofit oriented companies that include the poor.

Thus, it is a more radical proposal in the structural change of the economic system through the change of its main institution, which is the company. And in that there is a very important difference. Then there are other differences such as the deep bond between the company on the one hand and those who are excluded on the other; the attempt to bring the governance structure of communion into the life of the company, etc.

How do you explain gratuitousness in the Economy of Communion?

There is a mistaken understanding of it: the entrepreneur produces wealth, does not worry about changing the relations of production and, when he has money, donates it to the poor. If that were so, it would be an uninteresting model and not at all innovative.

We talk more about gratuitousness, and less about donation, because gratuitousness coexists with contracts, with debtors, with relationships within the company, with community relations. And therefore, even companies that do not donate their profit practice the culture of gratuitousness.

Half of these companies have no profit because they are either “in the red” or because they are nonprofit companies such as social cooperatives. Gratuitousness, therefore, is not simply giving away money. It is much deeper. For example, the entrepreneur mainly donates talents, resources, not so much money.

Thus, the culture of gratuitousness is very important, but it should not be understood as philanthropy, it should not be understood as donation but rather as new relationships of gratuitousness, a gratuitousness that perhaps should coexist with the notion of contract.

Therefore, the gratuitousness we speak of is not opposed to the contract, to the debtor: it is a dimension of life. We speak of love, of gratuitousness, of agape, because it is not so much “what we do” but “how we do it.” It’s a lifestyle.

How does gratuitousness distinguish itself from charity?

Gratuitousness is rooted in reciprocity. It is a process that begins, as with a donation, but then develops and lasts over time within the community. It´s not only the act of a person. In this sense, the European culture is different from the American culture, where it is considered normal that an entrepreneur makes consistent donations.

Not being used to the philanthropic model, but to the communitarian model, Europeans do not have the idea that it´s the individual that provides from his own wallet, a task that we attribute to the state or the community. And it is in the community that reciprocity can be fully expressed, because it is not simply charity but a model of relationships. Poverty itself is a relationship, not a status.

Does gratuitousness have limits?

The act of generosity is fragile by nature and exposed to opportunism. Risk is inevitable, but it is not a good reason to not take it. Building communities of solidarity for more sustainable dynamics works also as a guarantee in this sense, because once the process of gratuitousness has been inserted into the communitarian dimension there can also be controls for it.

What are the main innovations of the Economy of Communion regarding labor relations, for example, the relationship between boss and employee? Is the boss always the boss and the employee always the employee?

We must also change the property rights of the company. It is not enough just to say that the entrepreneur, with good motivation, is selfless. It is also necessary to change the relationships within the company.

In certain countries of the world, there are already participatory experiences, also in the contract. In other countries not, but there is a movement that will surely lead to overcoming the traditional way where there is the boss on one side, and the employee on the other.

What are the main difficulties of the Economy of Communion? And what contributions can it make to today’s dominant global liberal paradigm?

Today, the Economy of Communion begins to be a project that produces different categories, such as fraternity, reciprocity, gratuitousness, happiness, and relational goods which are being accepted by some sectors. They are original categories, also theoretical categories, born within the Economy of Communion.

But it is still a seed, that is, it is still in the beginning, because it is a very complex project. We are still in the early hours of a day. But there is something already. There is an important trend and, above all, we are beginning to see a growing interest by some universities. Recently, universities – in Africa, Chile, and Italy – have inserted, within the curriculum of studies, courses on Economy of Communion.

There is a growing movement. The trend is very positive. But the processes are long because it is a very complex organism. And the more complex the organism, the longer is its growth. For example, a cat, after three months, is already an adult; a man needs 20 years. Since our charisma is very complex – it is a spiritual, religious charisma that has many dimensions, from art to culture, from sports to politics – it needs more time to develop and understand its innovations because there is a much longer gestation. Published in IHU Online