The twentieth and twenty-first centuries have arguably been an epoch of the worst structures and tributaries of the root cause of acute global imbalances in wealth distribution and economic injustices, which have rendered most of the world’s population poor and unable to live their lives in dignity.

These global inequalities have not only compromised the dignity of innumerable people worldwide but, together with exploitation-driven environmental degradation, propelled us into an era of the climate crisis that has exacerbated the suffering of the poor. The gap between those living in obscene luxury and those living in abject poverty has never been this wide.

There are not many reasons for the above phenomenon, but they are complex. Moreover, it is fairly simple to attribute this unethical and morally undesirable situation to the unscrupulous betrayal of the common good, an integral principle of “our best kept secret.”

The Social Doctrine of the Church (SDC) is a formal body of modern social teachings of the Catholic Church, developed in the 19th century. It has for a long time been referred to as the best-kept secret because of the obliviousness of many Catholics vis-à-vis this critical dimension of their faith and the little attention it is given in many institutions like parishes and schools.

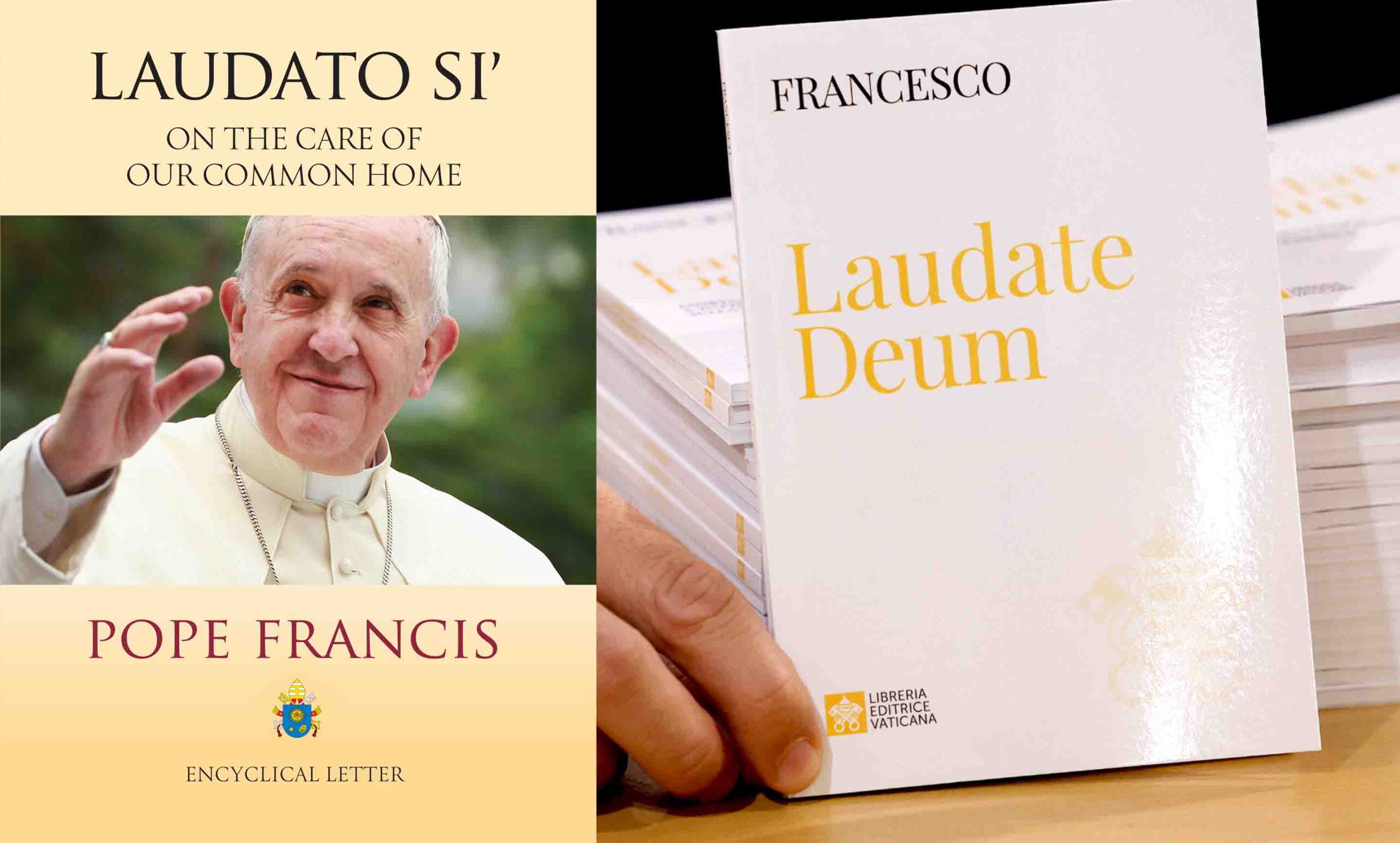

Although there is no official list of documents making up the SDC, there has been–since the May 1891 ground-breaking encyclical of Pope Leo XIII Rerum Novarum–a consensus regarding which documents should fall into this category. As a literature written mainly by popes and bishops, the Church leadership responds through SDC to countless political, economic, and social issues, including injustices of our time. It is based on Scripture, reason, Tradition or heritage and the people’s experiences.

Catholic Social Teaching is an essential element of our faith that expresses the relationship between our faith and reason (fides et ratio). Principally, it is a continuation of the mission of Christ to build the kingdom of God. As Pope Francis stated in Gaudete et Exultate: “Just as you cannot understand Christ apart from the kingdom he came to bring, so too your personal mission is inseparable from the building of that kingdom… Your identification with Christ and his will involve a commitment to build with him that kingdom of love, justice, and universal peace” (n. 25).

THE PROMOTION OF HUMAN DIGNITY

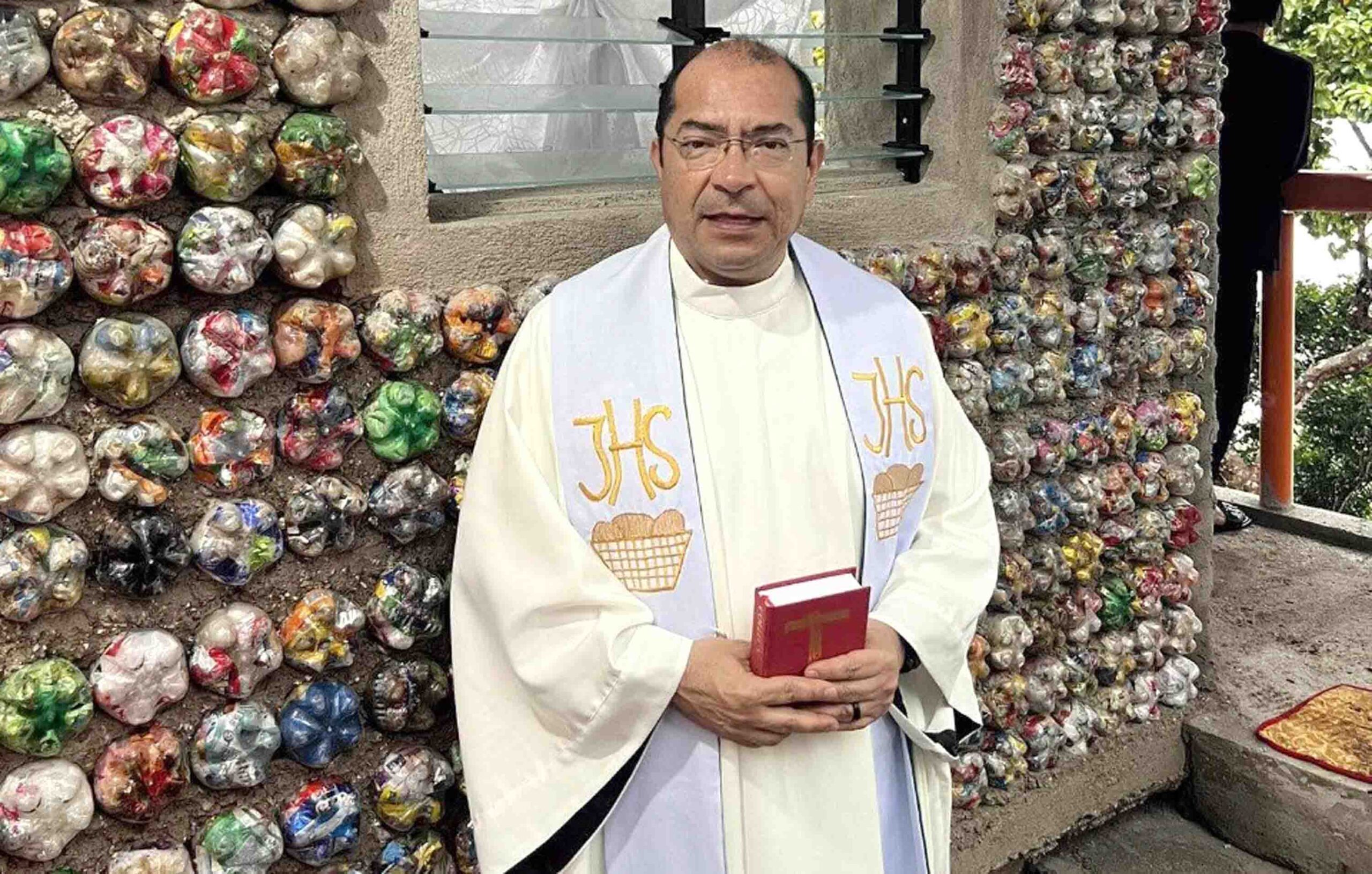

This mission necessarily demands that the Church accompany God’s people–as a protagonist of the common good and the promotion of human dignity–in all spheres and walks of their lives, especially in the economic, political, and social areas. The involvement in the latter have, nonetheless, often attracted venomous criticism towards the Church and accusations of meddling in affairs that she should not be involved in, as was the case during the apartheid years in South Africa. The Church did, however, through persistence and conviction in the SDC, win a few battles against the racially oppressive regime that systematically degraded the dignity of black people.

In the important areas of human development and education, the Church managed after many lengthy negotiations, to convince the government to allow private schools to admit children of all races legally. Advocating the common good and dignity of non-white South African learners, the Church, through its schools, created opportunities for access to good education for many who were not only poor but also deprived of good quality education on racial grounds.

This dedication to helping the marginalized gain access to education continued into the post-apartheid era when migrants, asylum-seekers, and refugees were also accorded access to education, especially when policies and practices hindered it. Through this, hope and dignity were restored for many.

As one of the most notoriously unequal societies in the world, South Africa has seen the gap between those living in opulence and those who are destitute, spiraling out of control, especially in the last twenty-five years. Obsolete policies, corruption, lawlessness, impunity, insecurity, poor public health and social care services, expensive and inaccessible good quality education, and a high rate of unemployment are just a few of the consequential factors that have systematically compromised the human dignity of so many South Africans, most of whom are living in dire poverty. This unspeakable situation demonstrates that the betrayal of the common good leads to the violation of the human dignity of those who are marginalized. This is a weighty concern for the Church.

The Church strongly believes that human life is sacred because of its inherent dignity, which emanates firstly from the intrinsic and inalienable image of God (Imago Dei) in each person. Secondly, the Church’s doctrine of the incarnation–God the Son becoming human–as professed in our creed, further affirms the dignity of each person. Consequently, human dignity becomes the underpinning principle of all the principles of the SDC and a recurring theme in most, if not all, of its documents.

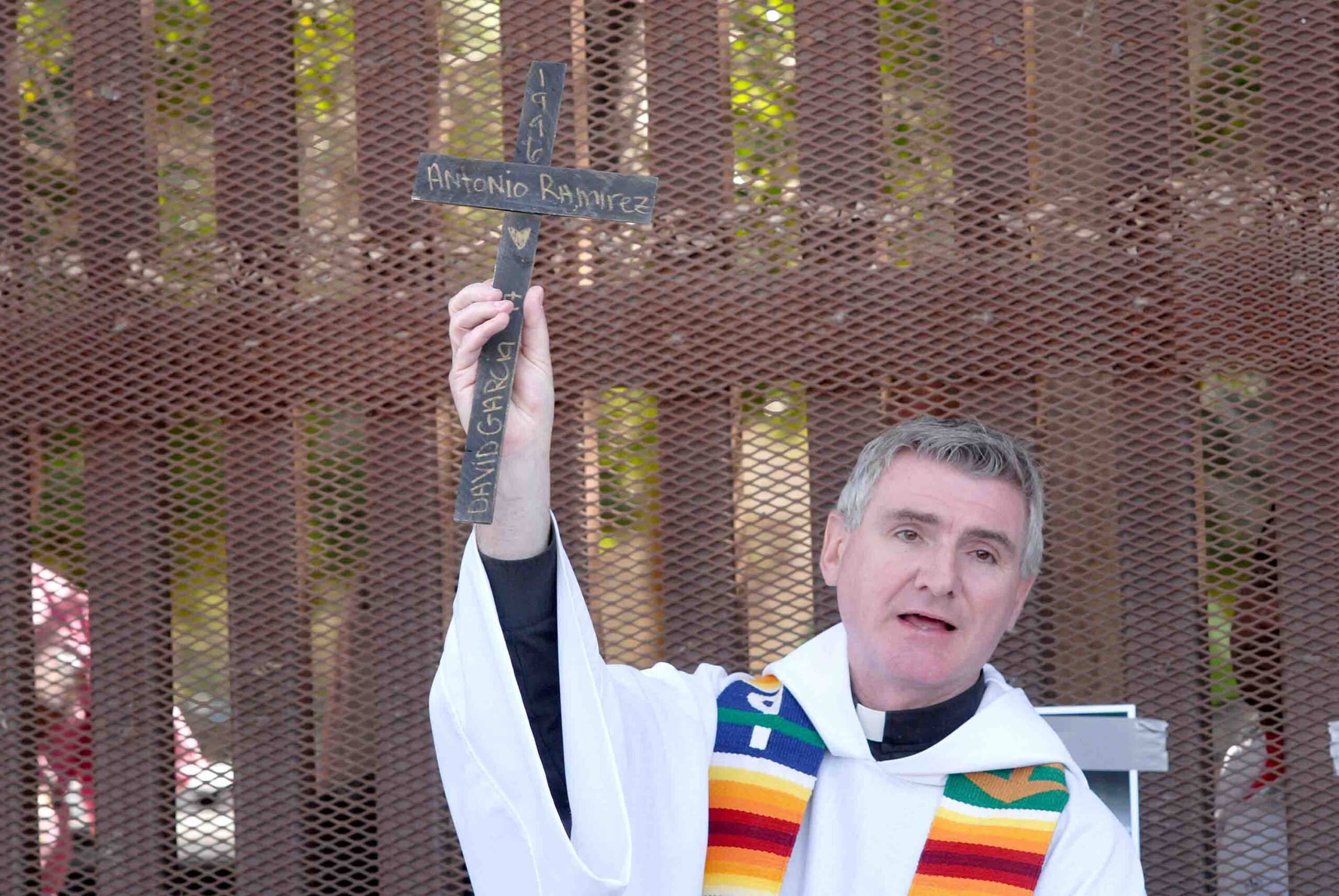

CARE FOR MIGRANTS AND REFUGEES

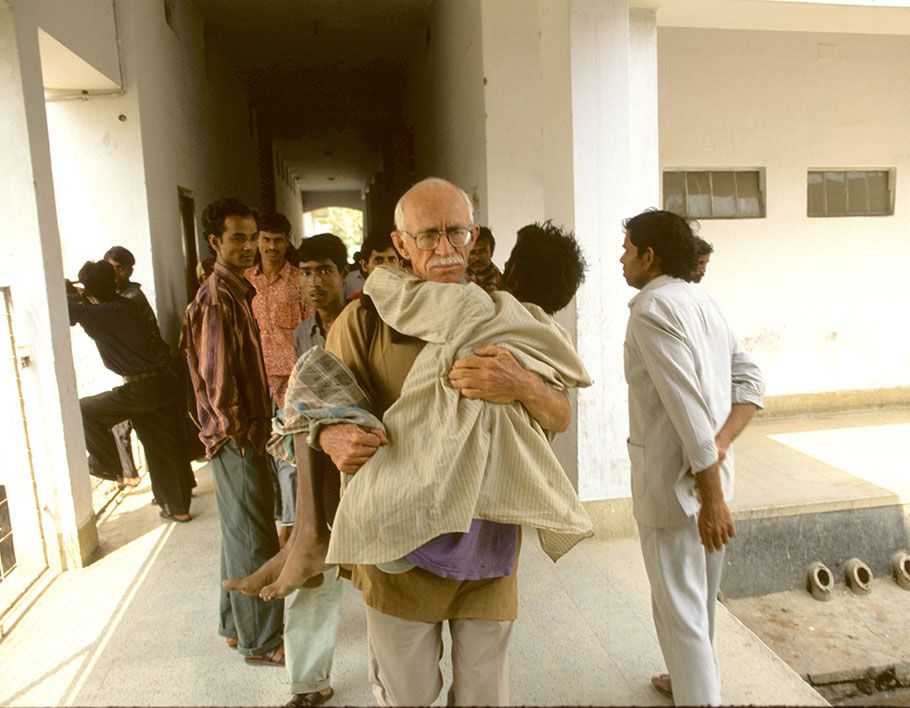

This commitment to the protection of the human dignity of all people, irrespective of their background or creed, has been manifested in her love and care for migrants, asylum-seekers, refugees, and all the (forcibly) displaced as well. The Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant People in Refugees: A Challenge to Solidarity refers to the tragedy of forced displacement as a “shameful wound of our time.” The Church “offers her love and assistance to all refugees without distinction as to religion or race, respecting in each of them the inalienable dignity of the human person created in the image of God” (n. 25).

Through the Southern African Catholic Bishops Conference (SACBC), the Church has not only produced literature calling for solidarity with the migrants, refugees, and the forcibly displaced, but it has also encouraged and promoted the establishment of Pastoral Care for Migrants and Refugees in all the SACBC dioceses and parishes.

In the 2019 bishops’ plenary meeting, a resolution was adopted to support this bold move to help restore the dignity of the displaced by establishing practical structures for the common good of all children of God. In journeying with the (forcibly) displaced in their most vulnerable moments, the Church puts into practice the SDC in protecting human dignity by promoting the common good.

With her teaching on the notion of human dignity, the Church has helped us understand the important concept of human rights better, for it is from the deep-rooted link with human dignity that we can fully appreciate human rights. This relationship is even alluded to in the preamble and opening lines of the United Nations’ 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “…recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world…”

THE COMMON GOOD

In accompanying the forcibly displaced, the Church understands that promoting the common good in host communities not only fosters the protection of human dignity but also enhances the possibility of people realizing their potential by enjoying their human rights.

In his encyclical Paecem in Terris, Pope John XXIII argued that “refugees are persons, and all their rights as persons must be recognised” (n. 105). He believed that they “cannot lose these rights simply because they are deprived of citizenship of their own States.” These rights are incontrovertible and should not be violated.

In its endeavor to promote and protect human dignity through its social doctrine, the SDC, the Church has, over the years, encouraged the principle of the common good for all to realize their potential to live their lives in dignity and to be accorded respect for their rights.

The interconnectedness of the common good and the promotion and protection of everyone’s human dignity, if fully appreciated and practiced, could help address the many social ills and divisions in society. The structures of sin that classify and divide the human family according to, inter alia, their wealth or lack thereof, according to their cultural, ethnic, racial, and religious backgrounds while rejecting and deferring the majority to the margins of society could hopefully be turned into structures of grace.