The first of the three key ideas contained in the newest papal encyclical is fraternity. It derives from the Latin term fraternitas and it carries at least two senses in the Francis tradition. First, fraternity serves as the term for a particular group of Franciscans. The second sense of fraternitas has to do with the kind of relationship one has with another: women, men, and even nonhuman creatures as part of God’s one family of creation.

To talk about fraternity as a disposition or value is to talk about how you view and relate to other people, including strangers and those who may be very different from you. It is about recognizing intrinsic familial ties with all people and creatures.

Pope Francis picks up on this Franciscan logic of fraternitas in the third chapter of Fratelli Tutti. Earlier in Chapter 2 of the encyclical, the pope uses the parable of the “Good Samaritan” (Luke 10: 25-37) to show how the Christian notion of relationship with others transcends the limits and qualifications we are quick to use in isolating ourselves from solidarity with others.

Francis highlights the demands that a spirit of fraternity places on us in relation to one another in human society. He notes that “for all the progress we have made, we are still ‘illiterate’ when it comes to accompanying, caring for, and supporting the most frail and vulnerable members of our developed societies” (Paragraph 64).

St. Francis instructed his followers that living the Christian life according to his distinctive vision boil down to “walking in the footprints of our Lord Jesus Christ.” Living like Jesus means prioritizing relationships above all else; it means caring for those in need, regardless of their identity or what affiliations they might have.

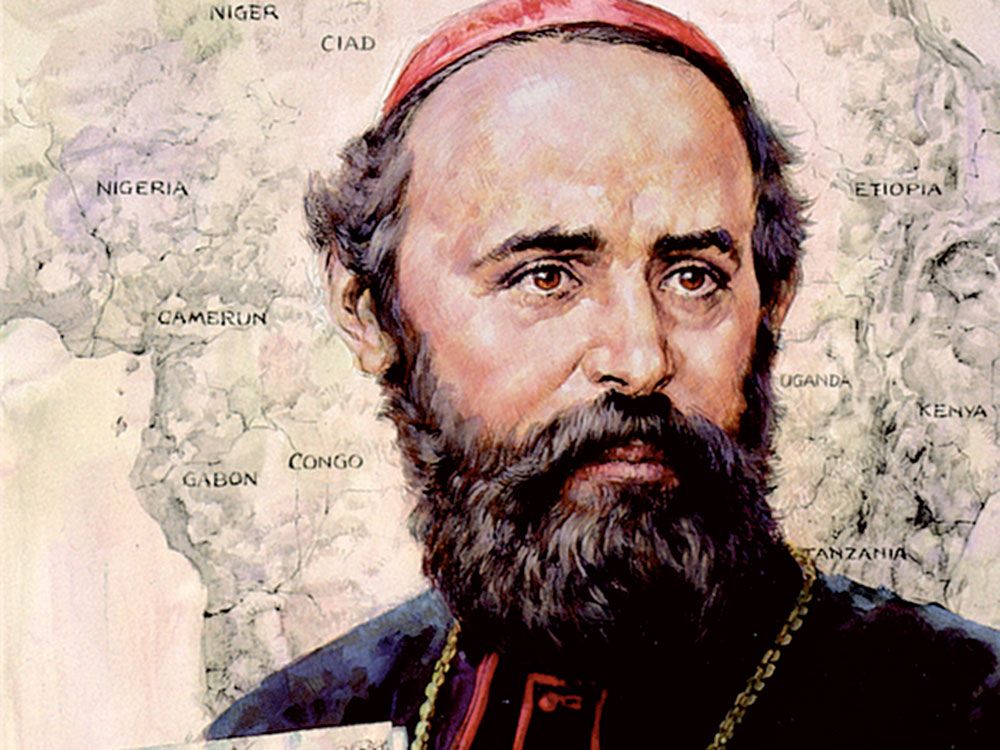

Early in the document, the pope recalls St. Francis’ famous encounter with Sultan Malek al-Kamil at Damietta, Egypt, in 1219. Drawing a connection to that historic episode of mutual respect, peacemaking, and fraternity, Pope Francis identified a comparable sense of encounter he had with Grand Imam Ahmad Al-Tayyeb, whom he met in Abu Dhabi in 2019.

At that meeting, the two religious leaders signed a document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together, which included the shared assertion that “God has created all human beings equal in rights, duties, and dignity, and has called them to live together as brothers and sisters.”

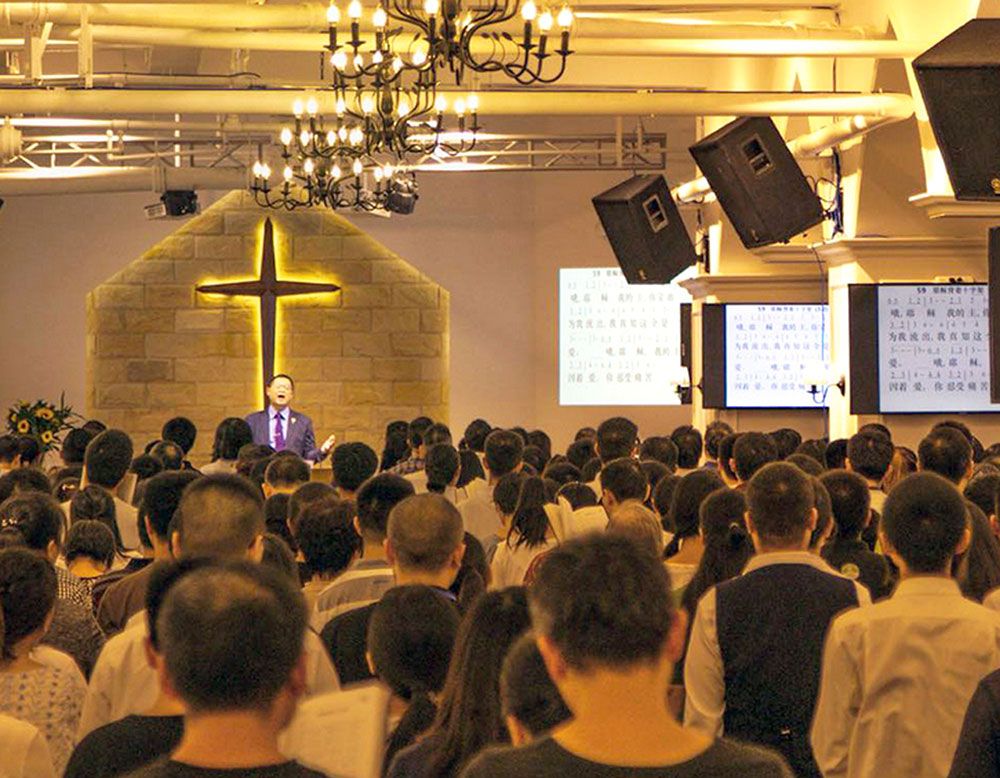

Francis, taking seriously the prioritization of fraternal relationship with all people modeled by St. Francis, describes this social teaching as directed not only to his Christian sisters and brothers but also addressed to all women and men of goodwill.

Building Bridges

St. Francis is known to have crossed many borders and built many bridges in his time. He crossed the border of the Fifth Crusade’s battle to engage in a peaceful encounter and exchange of ideas with the Sultan, despite the vilification of Muslims by the majority of Christian Europe at the time, including and especially by Pope Innocent III.

He even moved across the border of species when he sincerely referred to nonhuman creatures as his “sisters” and “brothers,” recognizing that lines of demarcation between the human and nonhuman are in some ways artificial constructs, given our interdependence on one another and universal reliance on our common source, which is God.

Today, Francis calls on all his brothers and sisters, regardless of their religious tradition or nation of origin, to “see things in a new light and to develop new responses” to the challenges before us (Paragraph 128).

Among these challenges is the increasing tendency that individuals and nations have to erect borders and walls, literal and figurative ones, which separate, isolate, and exclude the most vulnerable in our world. Francis’ consistent critiques throughout the encyclical of consumerism, capitalism, nationalism, xenophobia, and other ascendant ideologies of our time also gesture to the importance of bridge-building between peoples.

The pope points to love as the necessary ground for our building a “culture of encounter,” which “means that we, as a people, should be passionate about meeting others, seeking points of contact, building bridges, planning a project that includes everyone” (Paragraph 216).

He speaks throughout Fratelli Tutti of the evils of apathy and indifference, a recurring theme in his preaching and magisterial teaching. These attitudes not only prevent us from the capacity for compassion–the ability to suffer with others in solidarity–but they also promote individualism that creates separation and prohibits authentic relationships. What results is not only social division but also tremendous suffering, which is felt most acutely by the poor and vulnerable.

The imposition of physical and ideological borders does great harm to human dignity, particularly for migrants and immigrants, which is why Francis strongly emphasizes the need for “fraternal gratuitousness” or the building of bridges to a better life for those who suffer the most without asking the costs (Paragraph 140).

This is only possible, the pope notes, if we measure ourselves not merely as one country competing against others but “as part of the larger human family.” He adds: “Only a social and political culture that readily and ‘gratuitously’ welcomes others will have a future” (Paragraph 141). It is only in the spirit of St. Francis’ fraternitas that such reforms can take place.

Peacemaking

Toward the end of Fratelli Tutti, Francis writes: “In many parts of the world, there is a need for paths of peace to heal open wounds. There is also a need for peacemakers, men and women prepared to work boldly and creatively to initiate processes of healing and renewed encounter” (Paragraph 225). Here he again embodies the wisdom of St. Francis as a promoter of peacemaking and reconciliation.

In his famous “Canticle of the Creatures,” St. Francis barely mentions human beings. When he does toward the end of the text, after invoking many other aspects of creation, he says that we humans are most authentic in keeping with God’s intention for us when we “give pardon,” “bear infirmity and tribulation” and “endure in peace.”

Similarly, Francis stresses the need for another kind of being in the world, one that is more human and one that returns to this foundational vocation wherein God calls all people to be peacemakers and reconcilers.

Authentic peacemaking requires truth-telling and a shared commitment to the good of the other. It also requires recognizing how decisions have consequences–sometimes dramatically negative ones–for “the more vulnerable members of society” (Paragraph 234). He adds: “Those who work for tranquil social coexistence should never forget that inequality and lack of integral human development make peace impossible” (Paragraph 235).

Francis, like his medieval namesake, does not condone “easy” forgiveness or reconciliation, which often comes at the expense of silencing or dismissing the discomfiting experiences and histories of those who have been victimized. Instead, he insists on the importance of memory in a manner evoking the theological concept “dangerous memory” of Fr. Johann Baptist Metz, and the rejection of decisions or actions arising from “fear and resentment” (Paragraph 266).

In the final chapter of the encyclical, the pope appeals to all religious believers, regardless of their tradition, to be agents of reconciliation, recognizing the fundamental commitment we all have to promote the common good.

Speaking from the Christian perspective, Francis ties together the importance of the example of Jesus Christ and fraternitas as the foundation for our universal human vocation to be peacemakers and reconcilers.

“For us, the wellspring of human dignity and fraternity is in the Gospel of Jesus Christ. From it, there arises, for Christian thought and for the action of the Church, the primacy given to relationship, to the encounter with the sacred mystery of the other, to universal communion with the entire human family, as a vocation of all” (Paragraph 277).

These three themes–fraternitas, crossing borders and building bridges, and peacemaking and reconciliation–only begin to signal the manifold ways the inspirational specter of St. Francis haunts this latest encyclical letter.

As the church begins to unpack the wisdom and challenges present in this teaching during the coming weeks, months, and years, the fullness of the Franciscan influence will become even more apparent. Published in National Catholic Reporter