The ICU was dim as the lights were low and the shades partially drawn. The constant monitoring of heartbeats sounded eerie in this quiet room. The “wooshing” sound of oxygen being pumped into this patients lungs reminded us of how dependent she was on the “life support” machine. The woman was 65 and had recently suffered a horrendous trauma. Her seven children were present as I began the ritual prayers for the dying.

I was a chaplain at this Level I Trauma Center of a hospital for many years. When I retired in 2006, I had spent 30 years of ministry in hospital settings. I probably have witnessed every type of trauma and death in this 600-bed facility connected to a 200-bed children’s hospital and a 150-bed rehabilitation center. Two skilled workers helped me in this ministry. I had studied and became an Assistant Physician in 1977. While at the hospital I also earned a certificate in Clinical Pastoral Education.

Dying and death are realities that everyone is afraid of. We all know that one day we will meet death. The only question is when and how.

Nowadays, many big hospitals have training programs for chaplains. Clinical Pastoral Education is a specialized program to train pastors and lay persons to be pastoral care resources and be part of the medical care team. These “chaplains” are called upon to help patients and families cope with the reality of death and the struggles with illnesses such as cancer, renal failure, heart attack, among others, loss of a child in pregnancy, etc. Patients and families are traumatized by these and a chaplain is often called to help them face and cope with such traumas.

Besides offering prayers or sacraments, the pastoral care department also offers alternative therapies such as Reiki, meditation, deep breathing exercises, music therapy — all these are part of the “armamentarium” of practices which assist patients and families in traumatic times.

THE PRIEST AS “A MIRACLE WORKER”

When I was first ordained in 1962, I was given multiple tasks and one of those ministries was to be chaplain of an inner city university hospital with an extremely busy Emergency Room. Many nights were spent in that ER with anxious families. During that time, I was strictly a “sacramental minister.” I was the final hope for the dying patient. If the medical team could not do “miracles,” I was there to give “the last rites.” I would be praying, anointing and giving assurance to the patient and family that he or she was assured of direct access to heaven. Given the “general absolution,” the “last rites” and “plenary indulgence,” remitting all “punishment for sin,” the patient was supposed to be spared of “purgatory.”

That was 50 years ago and I had only performed what thousands and thousands of priests before me had done for so many years. We were been called to ease the passing away of a patient into eternity and to comfort the family with the hope for everlasting life.

Since then, changes have taken place. Theology has shifted its thinking. Vatican Council II replaced a significant part of the “priest as a miracle worker” with a deeper understanding of the “praying for the sick” and adding a real dimension of the family gathered in prayer with the sick or with a dying loved one.

The priest was no longer seen as the “cavalier” charging in, at the last moment, to rescue a patient from dying without the “last rites.” Rather, the priest was seen as part of the community of prayer, encouraging the patient and family to be open to whatever happens and to trust that, no matter what, the patient and family will have the strength and resilience to accept the outcome because of God’s mercy and love.

The chaplain’s role has switched from a sacramental “cure all” to a true healer and counselor to the patient and family and even to the staff of the hospital. Near death, many people get angry with God. They do not want to see a priest or chaplain around. His presence means “death” for the patient; the “black suit” and “collar” means the end has come.

A PART OF THE HEALING PROCESS

To change this negative image to positive is a real challenge for those in the pastoral care. Many times, I have been asked by the family not to go into the patient’s room because my presence would be a scare more than that of a funeral director.

Pastoral care for the sick means a twofold shift in thinking:

The family has to understand that pastoral care is a positive experience for themselves and for the patient. Their fears have to be allayed by an understanding that the person coming to them, as a chaplain, has significant training in crisis situations with families and patients. These chaplains are not here simply to pray for some miracle. They are part of the total healing process in a hospital setting.

At the same time, the priest or chaplain has to know the fears and anger that enfold the patient and family and, in a significantly healing way, reach out and touch their hearts with care and loving consolation. The chaplain may have never met the patient nor this family before but, at this very moment, she or he truly becomes a member of this family.

Surely, sacraments and prayers have a great part to play in moments of illness, but it is the loving support of being with and the caring of the “caregiver” which is the most important part of this care process.

I want to return to my first story of the mother in the ICU, prepared to have the “life support systems” removed following this horrendous trauma. All of her children were in the room as we prayed, but a couple of them left the room because they could not take the pain of seeing their mother die. I gathered them all together in the ICU with the mother. As we stood in prayer, I said to them: “Please stay and be with your mother. With great pain in delivery, she gave birth to each of you into this world. It is now your turn to be with her and share some pain of her birth into “eternal life.”

JUST SHARING THE LOVE

I have no idea where that thought came from but it seriously touched their lives and they were all happy to remain and be with their mother. Her death was a time of true love and family care. It was not the sacraments that really helped this family; it was the encouragement for this family to share themselves lovingly with their mother and with each other at her deathbed.

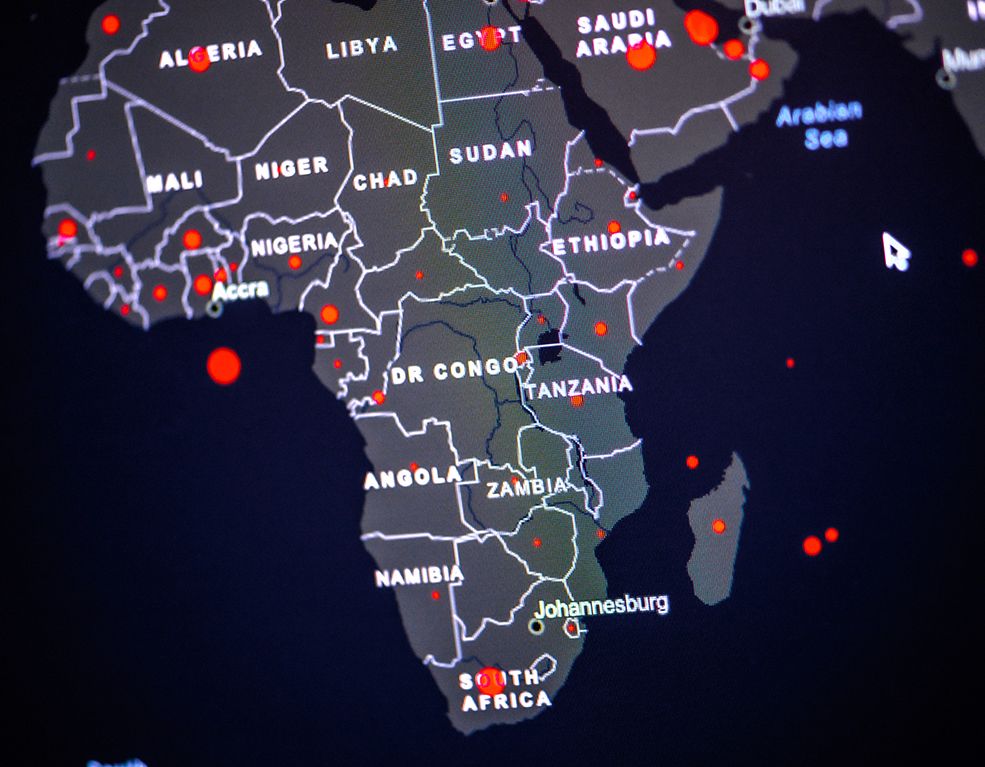

The role of the chaplain has really shifted with the advances of medical care and the combination of pastoral care working with the medical team. With further advances in counseling and rethinking of theological premises, pastoral care becomes even more critical in the lives of patients and families. Is pastoral care relevant in this contemporary scene? Absolutely!

From the time I was ordained in 1962, I think my main mission has been to “bury” my family. Over these years, I have presided over and celebrated the liturgies and given the homilies for my parents, my brother, numerous aunts and uncles, cousins and friends who were part of my family. I have experienced in my life the pain of it all. For many families and friends, I was there as the “pastoral care” person, supporting them and their respective patients.