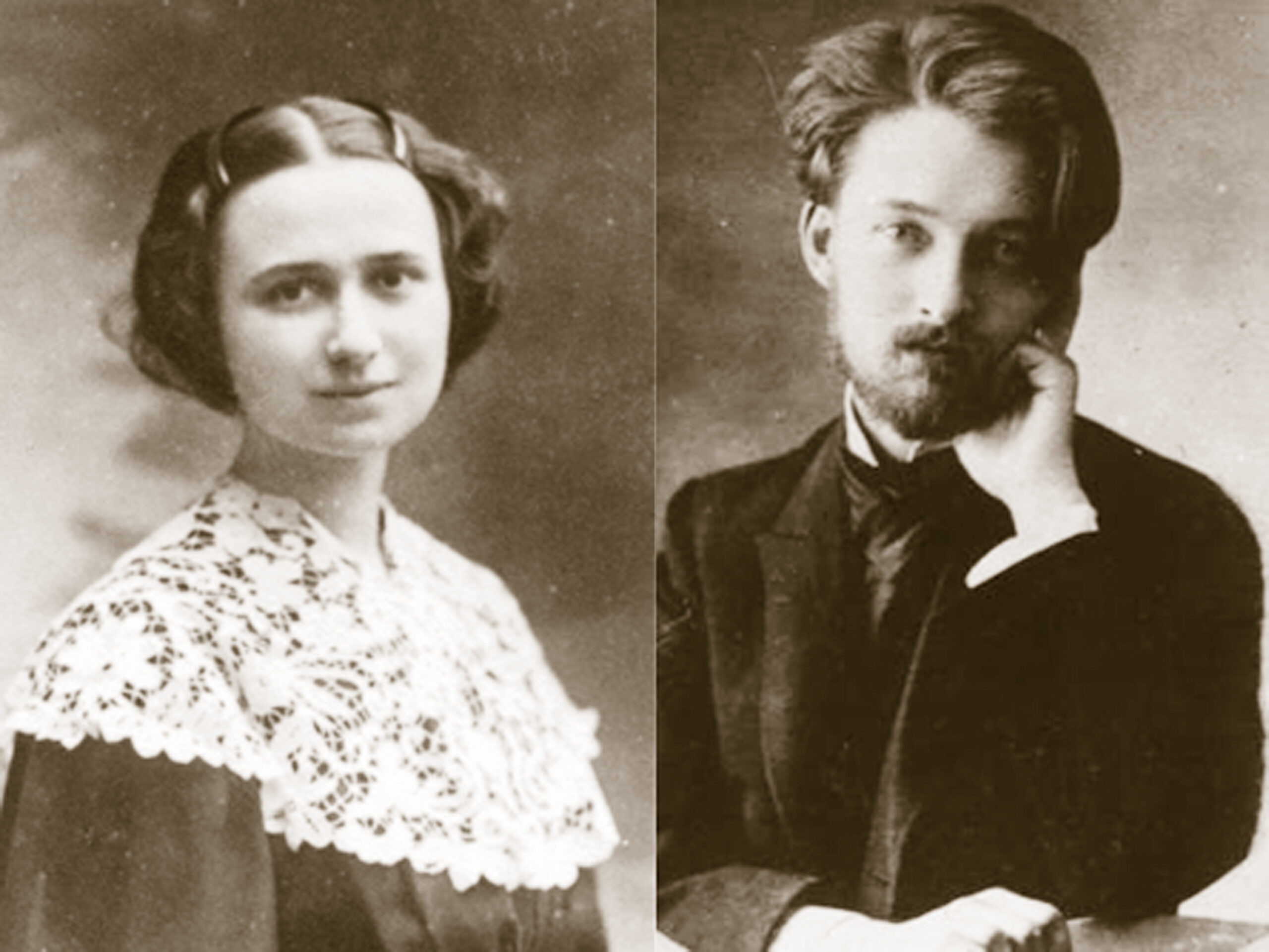

When the Russian young woman, Raissa Oumansov, began her studies at the University of Paris, she was seventeen years old and the year was 1900. It was a time of great scientific achievements and the Sorbonne was one of its centers. Marie and Pierre Curie, for example, had discovered radium there only two years before. It was natural, therefore, for Raissa to turn to the sciences for the answers she sought. To her dismay, however, she soon discovered that her professors were either strict materialists or simply did not pose for themselves questions concerning truth and meaning. Hope began to wane in her heart. Yet, she also continued to await “some great event, some perfect fulfillment.” The first step toward that fulfillment came when she met the man who would become her greatest companion during her earthly pilgrimage: Jacques Maritain.

Almost from the moment that Jacques Maritain introduced himself to Raissa, they became inseparable. They were both students at the Sorbonne, he a year older than she, and they both were searching for the meaning of their lives. Jacques Maritain came from a family that embodied the values of the French Revolution. He discovered, however, what many others of his generation would one day recognize: the agnosticism that was their heritage was too thin a soil for the sense of justice that burned in their hearts. To withstand the winds of tyranny, justice needs deep roots and a rich soil in which to sink them. It was during his search for that rich ideal soil that Jacques encountered Raïssa. In the friendship that grew between them, they undertook the search together.

In the midst of their distress, Jacques and Raissa reached a fateful decision that would shape the rest of their lives. While strolling through Paris, they both agreed that if it were impossible to know the truth, to distinguish good from evil, just from unjust, then life was not worth living. In such a case, it would be better to die young through suicide than to live an absurdity. They were spared from following through on this because, at the urging of their friend, Charles Péguy, they attended the lectures of Henri Bergson at the Collège de France. Bergson’s critique of scientism dissolved their intellectual despair and instilled in them “the sense of the Absolute.” Then, through the influence of Léon Bloy, they converted to the Roman Catholic faith in 1906.

God, in His great mercy, led them to Christ, to baptism in the Catholic Church and to the consolation of the Eucharist. In reading Bloy’s great novel, The Woman Who Was Poor, the Maritains encountered the greatness of the Christian saints. “What struck us so forcibly on first reading Bloy’s novel was the stature of this believer’s soul, his burning zeal for justice, the beauty of a doctrine which, for the first time, rose up before our eyes,” they later confessed.

Upon meeting Bloy and his family, they were even more impressed. His poverty, his faith, his heroic independence, all spoke to the young Maritains of the life-giving mystery of Christ. Entering Bloy’s home seemed to them a homecoming. In particular, by leading Raissa to Christ, Bloy gave back to her the Jewish faith of her childhood, now brought to completion in the New Covenant in Christ’s Blood.

A domestic community of prayer

Jacques Maritain was born in Paris on November 18, 1882, the son of Paul Maritain, who was a lawyer, and his wife Geneviève Favre and was reared in a liberal Protestant milieu. He was sent to the Lycée Henri-IV. Later, he attended the Sorbonne, studying the natural sciences: chemistry, biology and physics. By that time, he had become an unbeliever.

Raissa Oumansov was born into a pious Jewish family of modest means in Russia in 1883. During the ten years that Raissa lived in the Russian Empire, she was deeply shaped by the piety and traditions of her observant family, especially by the example of her maternal grandfather. Impressed, even at an early age, by his joy and gentle goodness, she learned, as the years passed, the deep source from which they sprang: “They came from his great piety, the piety of the Hasidim, the Jewish mystics. My grandfather’s religion was one altogether of love and confidence, of joy and charity,” she wrote. Raissa’s understanding of her Hasidic heritage is best seen in her later description of the work and personality of another Russian Jew, her friend, Marc Chagall, the painter loved by Pope Francis.

When Raissa was barely ten, her parents decided that they should emigrate as a family to France. They settled in Paris. Paris would become for Raissa her second homeland, more beloved to her than any other place on earth. Exile from their homeland not only uprooted them from their friends and family; it also occasioned a loss of faith. But then, Jacques appeared on the horizon of Raissa’s life and their destiny took a turn for the better.

Jacques and Raissa were receptive to Bloy’s message. In 1906, together with Vera, Raissa’s sister, they were baptized into the Catholic Church, with Léon and Jeanne Bloy as their godparents. On that occasion, Jacques and Raissa had their marriage blessed which they had contracted civilly in 1904. From that point on, Raissa began to discern the features of her vocation. She was being called to live in union with Christ. She was also being invited, through a life of prayer and study, to put into words – in prose and poetry – the truths she was now discovering in Christ.

The years between their baptism and the outbreak of the First World War were a time of spiritual gestation for the Maritains, and for many others in Europe. Those years saw the conversion of Jacques’ sister and Raissa’s father. A number of their friends also converted at this time, including two who had become dear to many in France through their writings and exploits: Jacques’ boyhood friend, Ernest Psichari, and his early mentor, Charles Péguy. During those years, Jacques and Raissa, with her sister Vera, became Benedictine Oblates, establishing together a domestic community of prayer and study.

Jacques and Raissa had decided to live as brother and sister, forsaking marital intimacy and the joys of raising a family in order to dedicate themselves more deeply to their vocation to serve the truth. It was also during those years that the Maritains discovered Thomas Aquinas and began, under the guidance of their Dominican mentors, to study his works in depth.

Although Jacques was already beginning to become known in France through his articles, it was only after the First World War that his life, as a philosopher, began in earnest. Having received a bequest in support of his work from a soldier killed at the front, the Maritains were able to buy a home in Meudon, a village not far from Paris, and bring their plans to fruition. They could live a life of prayer and study, and make their home a center for Catholic thought and culture, under the patronage of St. Thomas Aquinas.

Their home became a place where artists and intellectuals could find friendship and lively discussion. The guest lists to their home during those years reads like a Who’s Who of the Catholic intellectual revival in France. It was during the Meudon years that Raissa’s public life as a writer and a poet began.

America and World War II

By the early 1930’s, Jacques Maritain was an established figure in Catholic thought. He was already a frequent visitor to North America and, since 1932, had come annually to the Institute of Mediaeval Studies in Toronto, Canada, to give courses of lectures. Following his lectures in Toronto at the beginning of 1940, he moved to the United States, teaching at Princeton University (1941-42) and Columbia (1941-44). When the Second World War overtook France in 1940, the Maritains were in America.

Unable to return to their homeland and their friends, they dedicated their energies to helping the young generation, that was undergoing the crucible of the war, find the deeper meaning of the events they were suffering. Moving to New York, Jacques became deeply involved in rescue activities, seeking to bring persecuted and threatened academics, many of them Jews, to America. He was instrumental in founding the Free School of High Studies, a kind of university in exile that was, at the same time, the center of Gaullist resistance in the United States.

To give courage to the young generations, Raissa told the story of the Catholic revival in France as she and Jacques had experienced it. The first volume, Les Grandes Amitiés (We Have Been Friends Together) appeared in 1941 and was followed by its sequel, Les Aventures de la Gräce (Adventures in Grace) in 1944. As a chronicle of the Catholic revival in France, these books are without equal. More than this, however, they offer us a theology of conversion and Christian vocation expressed in a narrative that traces the effects of God’s mercy upon the lives of a generation searching for meaning.

Following the liberation of France in the summer of 1944, Jacques was named French ambassador to the Vatican, serving until 1948, but was also actively involved in drafting the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948).

Integral humanism

Maritain was a strong defender of natural law ethics. He viewed ethical norms as being rooted in human nature. We know the natural law through our direct acquaintance with it in our human experience. Of central importance is Maritain’s argument that natural rights are rooted in the natural law. This was key to his involvement in the drafting of the U.N.’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Maritain advocated what he called “integral humanism.”

He argued that secular forms of humanism were inevitably anti-human in that they refused to recognize the whole person. Once the spiritual dimension of human nature is rejected, we no longer have an integral, but a merely partial, humanism, one which rejects a fundamental aspect of the human person. Possibly, his most famous book is “Integral Humanism” (1936) where he also develops a theory of cooperation, to show how people of different intellectual positions can, nevertheless, cooperate to achieve common practical aims. Maritain’s political theory was extremely influential, and was a primary source behind the Christian Democratic Movement.

Maritain’s emphasis on the value of the human person has been described as a form of personalism, which he saw as a via media between individualism and socialism. Maritain’s Christian humanism and personalism have also had a significant influence in the social encyclicals of Pope Paul VI and in the thought of Pope John Paul II. One consequence of his natural law and natural rights theory is that Maritain favored a democratic and liberal view of the state, and argued for a political society that is both personalist, pluralist, and inspired by Christian values.

Raissa’s legacy

In 1960, Maritain and his wife returned to France. Following Raissa’s death later that year, Maritain moved to Toulouse, where he decided to live with a religious order, the Little Brothers of Jesus. He also published Raissa’s writings under the title “Raissa’s Journal.” It was a real revelation. From the earliest days of her conversion, Raissa felt an intense call to contemplative prayer. It was during this period that Raissa began to write her Journal, which was published only after her death.

With arresting clarity, she describes the Lord’s action in her life and her struggles to understand and respond. Brief insights – “to love and understand one’s neighbor, one must forget oneself” – are interspersed with descriptions of her struggles and pearls of calm wisdom, such as the following: “Error is like the foam on the waves, it eludes our grasp and keeps reappearing. The soul must not exhaust itself fighting against the foam. Its zeal must be purified and calmed and, by union with the Divine Will, it must gather strength from the depths. And Christ, with all His merits and the merits of all the saints, will do His work deep down below the surface of the waters. And everything that can be saved will be saved.”

The Journal also provides the record of her awareness that the Lord was inviting her to accept a share in His suffering. She wrote: “During silent prayer, I feel inwardly solicited to abandon myself to God, and not only solicited but effectively inclined to do it, and do it, feeling that it is for a trial, for a suffering, for which my consent is thus demanded. I make this act of abandonment in spite of my natural cowardice.”

In his solitude, Jacques had a moment of glory when he was invited to the Second Vatican Council as observer and it is to him that Pope Paul VI, his pupil and admirer, presented his “Message to Men of Thought and of Science” at the close of Vatican II. During this time, he wrote a number of books, the best-known of which was “The Farmer of the Garonne” (a work sharply critical of post-Vatican Council excesses), published in 1967. In 1970, he petitioned to join the Order, and died in Toulouse on April 28, 1973.

At the time of his death, Maritain was undoubtedly the best known Catholic philosopher in the world. The breadth of his philosophical work, his influence in the social philosophy of the Catholic Church, and his ardent defense of human rights made him one of the central figures of his times. Maritain is the author of some sixty books and hundreds of scholarly articles. His philosophical work has been translated into some twenty languages. He is buried alongside Raissa in Kolbsheim (Alsace) France. The cause for his beatification and his wife Raissa’s is already on the way.