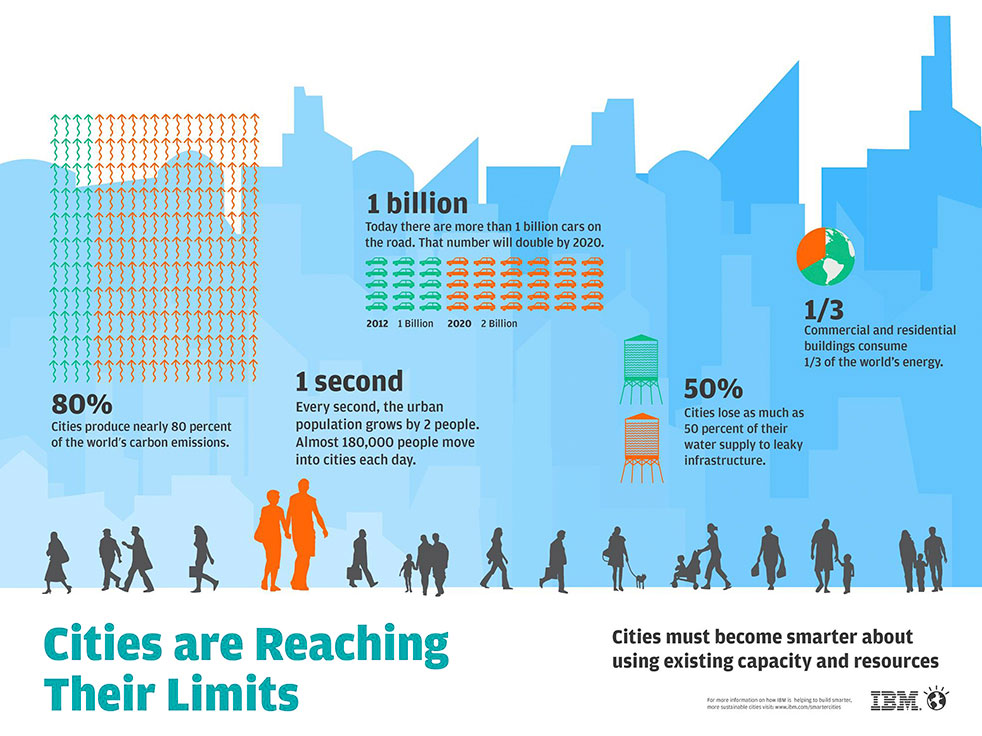

Food, needless to say, is necessary to live a dignified life. The right to food is also a basic human right. However, millions still die of hunger today. Eradicating extreme hunger and poverty is even the first of the eight Millennium Development Goals that the United Nations targets to attain by 2015. A year shy of that deadline, there is still scarcity despite the earth’s bountiful resources.

To end hunger is an advocacy that global leaders share with the Church… for bread is central to the celebration of the Christian faith. Pope Francis even said, “it is intolerable that thousands of people continue to die every day from hunger even though substantial quantities of food are available and often simply wasted.” The Holy Father said there has to be a way “to enable everyone to benefit from the fruits of the earth.”

For a confederation of 164 Catholic organizations worldwide, hunger is not caused by mere lack of food but by lack of justice, which causes the unequal access to adequate and nutritious food. To pioneer lay mobilizations to end hunger, Caritas Internationalis launched last December 10th the “One Human Family, Food for All” advocacy, urging all to “work as one to end hunger by 2025.”

Aside from reducing food wastage and promoting urban gardening, Caritas Intertionalis members are advocating agrarian reform as a means to reduce hunger incidence in their respective countries. The connection between the fight against hunger and the agrarian reform advocacy rings true especially in the Philippines, where unsuccessful implementation of the agrarian reform program has long worsened poverty levels, increased the unemployment rate, and exacerbated hunger incidence in the rural areas. If it is considered a scandal to see millions of hungry people despite the earth’s bounty, Manila Auxiliary Bishop Broderick Pabillo considers it an outright injustice that 97 million Filipinos do not have a fair share in the resources of the country’s 7,107 islands. “According to the social teachings of the Church, the earth belongs to all and not only to some. It is not fair when only a few have lands while the majority are landless,” he said.

As the current Chairman of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) National Secretariat for Social Action, Justice and Peace, Pabillo and his predecessors have been at the forefront of agrarian reform advocacy in the Philippines – a country that once taught its neighbors how to plant rice but is now dependent on imports to maintain food security. Even before Pabillo took the helm of the CBCP NASSAJP, the Catholic hierarchy has been a staunch supporter of farmers who embarked on marches, camp outs, rallies and hunger strikes in a bid to get the government’s attention to genuinely implement social justice through agrarian reform. In fact, the CBCP advocated for the genuine implementation of Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) during the celebration of the Second National Rural Congress in 2008. The country’s prelates, in a statement, said “abandoning the agricultural sector will not only threaten the farmers but also imperil food security itself. Conversely, distributing land to small farmers will provide equitable economic opportunities in the rural area and eventually reduce poverty and unrests.” The CBCP statement has been significant to convince Congress to enact CARP extension with reforms (CARPER) in 2009.

And last January, right after the CBCP plenary assembly, Pabillo and other bishops sent a letter to President Benigno S. Aquino III urging government to continue the acquisition of private agricultural lands and the redistribution of these to landless farmers under CARP. If it weren’t for the bishops, the farmers’ pleas would fall on government’s deaf ears and their demonstrations ignored by the State’s selective eyesight. Lawyer Christian Monsod, convenor of the Multi-Stakeholder Task Force on Agrarian Reform, quipped: “Government officials are afraid to not talk to the Church. They may say no to us but I doubt it if they can say no to the Church.”

In the letter dated January 22, 2014, bishops, civil society organizations, and farmers groups have requested President Aquino to extend the implementation of the land acquisition and distribution (LAD) component of CARP for two more years or indefinitely, until all private and public agricultural lands are covered by the program. The LAD component of CARP expired on June 30, more than 25 years after the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law was enacted in 1988. The agrarian reform advocates wrote: “Decisive action to ensure the success of CARP will be especially timely, given that 2014 has been declared as the International Year of Family Farming by the General Assembly of the United Nations. There would be no stronger statement that your administration champions the cause of family farmers by sustaining the very program that would give land to the landless, and thus allow the family farm sector to flourish within our country.”

Their demands also include the installation of a new Agrarian Reform Secretary, the absolution of farmers’ unpaid amortization on their CARP-awarded lands, and the creation of an independent commission to audit the government’s implementation of agrarian reform projects. The appeal letter got extensive media coverage but still, the government turned a blind eye and a deaf ear to the request. President Aquino and his allies in Congress are yet to map out the future of CARP three months before a crucial component of the program is set to expire.

MEANT TO FAIL

Farmers and agrarian reform advocates have repeatedly called for the resignation of incumbent Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) Secretary Atty. Virgilio delos Reyes early in Aquino’s term. Citing the DAR chief’s wanting performance based on the agency’s accomplishment under the current administration, they urged the President to replace delos Reyes saying he “does not fit the role of a transformational leader for the demanding task ahead for CARP.”

In September 2013, delos Reyes admitted that at least 822,488 hectares of land remain to be covered by the program before the June 30 deadline and that 210,067 hectares of the balance have been tagged as “problematic.” Delos Reyes also admitted that DAR has yet to start the painstaking process of awarding portions of the Hacienda Luisita to its farmer-tenants, almost three years after the Supreme Court ordered its actual distribution in 2011. The Hacienda Luisita is a 5,000-hectare sugarcane plantation in Tarlac province owned by the President’s family, the Cojuangcos. At least 6,212 tenant-farmers are expecting to own 6,600 square meters of land from the 4,099-hectare distributable area of Hacienda Luisita. Yet despite government’s initial payment of at least PhP471 million as just compensation to Hacienda Luisita Inc. (HLI), DAR is still struggling to install the beneficiaries in their CARP-awarded lands.

Even the President’s promise of issuing notices of coverage to the LAD-targeted properties this year seems doomed to fail because of DAR’s performance. But despite the agency’s backlog and the farmers’ appeals, Aquino kept delos Reyes in power, saying the official still enjoys his trust and confidence. This had raised the brows of agrarian reform advocates. “Is it by design or by incompetence that the CARP is not completed?” Pabillo said in apparent frustration: “I don’t know if it is just a lack of resolve or if there is really an intention not to make agrarian reform succeed.”

But how could one expect Aquino – born to a wealthy landowning clan – to have the heart to support a program that will be disadvantageous to his landed kind? Monsod claimed that the Aquinos – both the incumbent President and his late mother, former President Corazon Aquino – have “only paid lip service” to CARP despite being propelled to power by the peasants they promised social justice to and whom they called their “boss.” It can be recalled that Mrs. Aquino was notoriously criticized during her administration for placing loopholes in the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law, such as the stock-distribution option (SDO), as a means for landowners to evade the mandatory coverage of CARP. Under the SDO, corporate landowners may give farmer-beneficiaries the right to purchase capital stock of the corporation instead of turning over their land for CARP coverage. For years, farmers held HLI stock certificates instead of actual land titles, which was supposed to be the essence of the program.

Even Monsod, who was a part of the commission that drafted the 1987 Philippine Constitution and was appointed Election Commissioner during Mrs. Aquino’s presidency, admitted that there was an intention for the CARP to fail from the start. “All social reform laws have loopholes because they were legislated by the elite and for the rich and the powerful to take advantage of,” he confessed.

The various circumventions of the law to avoid CARP coverage have been the ultimate reason why Monsod and other agrarian reform advocates, including the bishops, are urging Congress to either enact a new and genuine agrarian reform law or establish an independent commission that will audit CARP implementation since time immemorial. Among other purposes, the proposed commission would look into the lands that avoided or circumvented the law, such as the voluntary land transfers, unwarranted exemptions and conversions, excessive retentions, or fake joint ventures. The commission can then take steps to have these declared null and void and subject the lands to coverage and distribution. “If you allow landowners who circumvented and defied the law to keep the land, it will make a mockery of the CARP,” Monsod argued. “They are keeping their land and they brag about the fact that they were able to circumvent the law. How can that be social reform when you allow that to happen?”

SUPPORT SERVICES

Ifugao Representative Teddy Brawner Baguilat, chairman of the Congressional Committee on Agrarian Reform, said that aside from a genuine agrarian reform bill, separate proposals to extend the LAD implementation by five more years and to amend the existing law on CARP have been submitted to the Congressional Committee on Agrarian Reform. He added that, while his Committee can endorse any of the proposed measures, the real battle will be at the plenary debate where landlords dominate the floor. “It cannot be denied that majority of those in Congress are landlords or are scions of landed families. But there are younger sets of legislators who are open to the concept of social justice and human rights. There is a general sense of social reform. But let’s see (how they handle their biases) at the plenary,” he said.

But if nothing could be done to extend the LAD component of CARP (beyond 2014), Monsod said the Aquino Administration should set up massive funding for support services “to show what can be done if it is done right.” As it is now, farmer-beneficiaries are complaining of dismal – if not utter lack of – support services such as access to credit facilities, planting technology, irrigation systems and farm-to-market roads.

The lack of support services for farmers was traced to the underfunding of CARP. Initially, the program has a funding requirement of P225 billion for its 20-year implementation. However, the landlord-dominated Congress only allocated P175 billion for the program and appropriated less than the P150 billion funding requirement for the five-year extension. Pabillo said the lack of support services has greatly affected the productivity of farmer beneficiaries. “It’s best to condone the unpaid amortization and unconditionally award the land to the farmers because there have been no support services to make them productive enough to earn,” the prelate said. Monsod added that recouping the investment in CARP or merely setting targets should not be the government’s motivation. “They missed the point; agrarian reform is not about numbers or deadlines. It is about the outcome. Have the lives of the farmers improved? Has rural poverty been reduced?”

GIVE IT A CHANCE

“Give CARP a chance” has been the farmers’ outstanding appeal to Congress. Monsod said a proper audit of the DAR’s performance, the continued implementation of CARP and sufficient funding for support services will put new life into the farming sector. “Imagine what that can do to the morale of the poor farmers!”

But if nothing can be done to implement agrarian reform under a government controlled by landlords, Monsod said the only hope is to help peasants to rise to the ranks of government. “Let us change politics at the top and develop leadership from below. We must develop leaders among the farmers and give them the chance to run this country because those of us in the ruling elite have failed,” he said.

For his part, Pabillo said it is important for the public to be awaken by the farmers’ plight. “There has to be awareness on social justice issues and there has to be a change of heart. Government will only change if officials have a change of heart. Even if you change the system, it will be futile if the hearts of those in power remain selfish,” he said.

Despite bleak hope for the genuine implementation of CARP, Pabillo said farmers’ mobilizations will persist even beyond the program’s life and until the peasants attain justice. “Until justice is not met,” the prelate said, “the Church’s support to the poor will carry on.”