In the wake of Haiti’s catastrophic earthquake, prominent advocacy groups are calling on the U.S. and the international community to reverse decades of racial and political discrimination and build relief and reconstruction efforts on human rights principles, transparency, and respect for the dignity of all Haitians. The director of one of the groups, Monika Kalra Varma of the RFK Center for Justice & Human Rights, commented: “Over the years, help for Haiti has been shaped by ideological politics and broken promises. Generally, the international community has made pledges to Haiti that remain unfulfilled. Donor states have human rights obligations to Haiti as well – they must do no harm. When states pledge funds to Haiti on which the Haitian people and the government rely to meet their needs, particularly monetary pledges to strengthen water, education, and health systems, and that money doesn’t come in, the donors violate their human rights obligations.”

Some development experts who have worked in Haiti for years spoke on condition of anonymity because they have friends and family members involved in the relief effort. “There have been hundreds of millions of dollars in development assistance that have gone to benefit Haiti’s elites – government, business and the military – at the expense of the country’s common people,” one source said. “These elites have abused international aid as they have done nothing to create an education system, a public health system or any meaningful infrastructure.”

Racial politics has always played a significant role in Haiti’s history. Haitian elites “tend to have lighter skin color than their darker-skinned brothers and sisters who make up the vast majority of Haitians,” the source said. At one point in its storied history, Haiti was divided into two sections: the lighter and the darker-skinned citizens. In 1806, Haiti had a black-controlled north and a mulatto-ruled south – merely five years after a former black slave, Toussaint Louverture, became a guerrilla leader and overthrew French rule, abolished slavery and proclaimed himself governor-general of an autonomous government. For decades afterwards, Haiti was crippled by reparations it was forced to pay to former slave owners.

Corruption and selfish interests

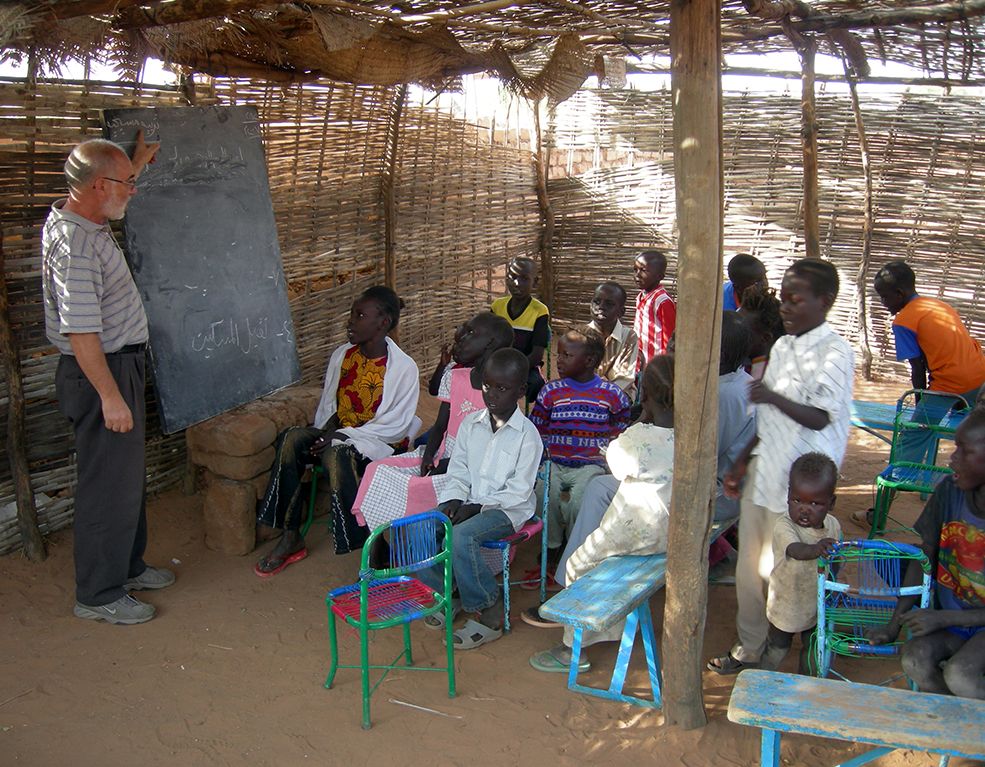

Another Haiti expert, Prof. Robert Maguire of Trinity College in Washington, said that the history of aid to Haiti has been a complex combination of corruption among the government and business elites of the country and the selfish interests of international investors from the private sector who “wanted to maintain the status quo” and who viewed Haiti as “a low-wage and stable dictatorship” able only to manufacture basic garments and other textile products. He proposes a 700,000-strong national civic service corps made up of Haitian youth who, he calls, the “wellspring of creativity, talent and potential.”

A civic service corps “would get the young and able out of the tent cities in and around Port-au-Prince to work. They could start with the once-iconic centre of the capital, but also could begin planting trees, working the fields and providing services in Haiti’s countryside,” said Maguire, who is an advisor at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Journalist Eric Michael Johnson, writing in The Huffington Post, notes that “Haiti has a historically unhealthy dependence on foreign commerce and finance, from the colonial days of the sugar trade to the current assistance provided by developed countries. Now, the same politicians and financial elites who helped create this mess are proposing an even larger program following the same mode.” Johnson writes that, “since 2004, Haitian exports to the United States have increased by 32% while, during the same period, the Haitian minimum wage has declined by 36%.”

Stop-start-stop politics

The Kennedy Centre’s Kalra Varma noted that multilateral aid has frequently been marked by stop-start-stop politics, with aid stopping when Haiti elects a leader not favored by donors. She cites the refusal of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) to release funds earmarked for water projects, which would have benefited the poor. “The IDB is controlled by its largest donor – the U.S. – which did not like Haiti’s government of the day,” she said.

She added: “All too often, aid has been slow to arrive, uncoordinated, and planned with no input from the people most affected – that legacy must and can end today. We have an opportunity to break away from the past and ensure that assistance is given in a way that strengthens Haitians’ fundamental rights to food, water, and health. The Haitian people deserve no less.”

Loune Viaud, director of Strategic Planning and Operations at Zanmi Lasante, a health organization, cautioned: “The only way to avoid escalation of this crisis is for international aid to take a long-term view and strive to rebuild a stronger Haiti – one that includes a government that can ensure the basic human rights of all Haitians and a nation that is empowered to demand those rights.”

The opportunity to bring change

Groups such as the Centre for Constitutional Rights (CCR), the Centre for Human Rights and Global Justice (CHRGJ), the Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti (IJDH), and TransAfrica Forum, cited past relief efforts in Haiti that were uncoordinated, unpredictable, and lacked community participation that led to increased suffering. They called on the international community to seize this opportunity to advance human rights and sustainability in the ravaged country.

“The magnitude of the catastrophe is not entirely a result of natural disaster but, rather, a history of deliberate impoverishment and disempowerment of the Haitian people through a series of misguided polices,” said Brian Concannon Jr., Director of IJDH. “Lack of donor accountability and continued aid volatility will only guarantee even greater suffering.”

In an editorial prepared for distribution, Kalra Varma and Kerry Kennedy wrote: “As international aid begins to pour into Haiti, we have to break away from past mistakes and bring real change to Haiti.” U.S and international aid efforts “could be characterized, at best, as unsustainable and, at worst, deliberately harmful,” they wrote. (Kerry Kennedy is the daughter of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.)

The editorial continues: “In 2000, the U.S. and the Inter-American Development Bank approved millions of dollars of what would have been life-saving loans for improvements to water, health, education, and road infrastructure, only to later withhold these funds because they opposed then President [Bertrand] Aristide. (…) While the loans were eventually released, the communities, where the very first water projects were to be financed, still lack access, ten years later, to reliably clean drinking water, contributing to countless deaths due to waterborne illness.”

It adds: “In 2004, the international community pledged a billion dollars to support Haiti. The RFK Centre, along with the health organization Zanmi Lasante and the NYU Centre for Human Rights and Global Justice, tried to track the fulfillment of those pledges, but never received clear and consistent answers from donor states on the status of the aid. (…) With no transparency or coordinating body to turn to, the Haitian people had no hope of knowing if that money ever got to Haiti, much less where it was directed and how it was used to improve their communities. Haitian government sources later confirmed that most of the pledges had never been fulfilled.”