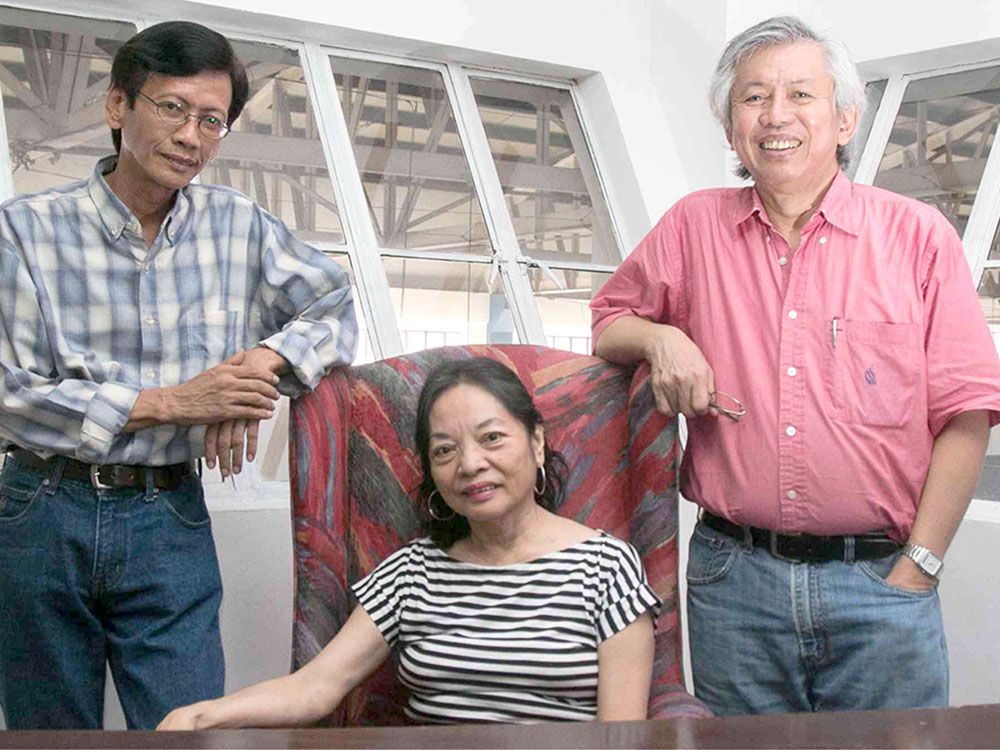

Nick Joaquin, the famous writer and journalist, had made many friends among the other writers through the years. Perhaps more than any of them, he was close to José “Pete” Lacaba. A journalist, writer and activist, Pete was working at the Asia-Philippines Leader with Joaquin when martial law was declared on September 21, 1972. Pete’s name was on the list of those wanted by the law but he managed to evade the first sweep of arrests and went underground. In 1974, he was caught and brought to Camp Crame where he was detained and tortured.

Amnesty International failed to free him. What happened next remains one of the best stories told about Nick Joaquin. He was declared National Artist for Literature in 1976. As Pete recalls, “Joaquin despised President Marcos’ declaration of martial law and loathed to receive his award unless he got it on his own terms.” Joaquin was advised to accept the award, and then ask for Pete’s release. Joaquin agreed.

During the cocktails after receiving the award, Joaquin approached Marcos and said: “I have this officemate, a writer, who is detained at Crame. Maybe he can be released already?” Marcos replied: “Ok, Nick, his release will be part of your award.” Marcos then called for Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile. The next day, Pete was released from detention.

Later, Joaquin kept his distance from power, studiously resisting invitations to attend state functions in Malacañang Palace. At a ceremony on Mount Makiling attended by First Lady Imelda Marcos, Joaquín delivered an invocation to Mariang Makiling, the mountain’s mythical maiden. He touched on the importance of freedom and the artist. He was never again invited to address formal cultural occasions for the rest of the Marcos regime.

A voracious reader

Nick Joaquín was born in Paco, Manila, one of ten children of Leocadio Joaquín, a colonel under General Emilio Aguinaldo in the 1896 Revolution, and Salome Márquez, a teacher of English and Spanish. As a boy, after being read poems and stories by his mother, Joaquín read widely in his father’s library and at the National Library of the Philippines. By then, his father had become a successful lawyer after the Revolution. When he died prematurely, Nick was only twelve.

The young Joaquín dropped out of school. He had attended Pacò Elementary School and had three years of secondary education at Mapa High School but was too intellectually restless to be confined in a classroom. Among other changes, he was unable to pursue the religious vocation that his Catholic family had envisioned to be his future. Joaquín himself confessed that he always had the vocation for the religious life and would have entered a seminary if it were not for his father’s death.

But his passion for reading remained. Aside from reading, Joaquín became interested in writing. At age 17, Joaquín had his first piece published in the literary section of the pre-World War II’s Tribune, where he worked as a proofreader. It was accepted by the writer and editor Serafín Lanot. After Joaquín won a nationwide essay competition to honor La Naval de Manila, sponsored by the Dominican Order, the University of Santo Tomas awarded him an honorary Associate in Arts and a scholarship to St. Albert’s Convent, the Dominican monastery in Hong Kong.

Provocative writer

After returning to the Philippines, Joaquín joined the Philippine Free Press, starting as a proofreader. He was soon noticed for his poems, stories and plays, as well as his journalism under the pen name Quijano de Manila. His journalism was both intellectual and provocative, an unknown genre in the Philippines at that time.

One of his contemporaries remarked: “The journalist Nick Joaquín has brought to the craft the sensibility and style of the literary artist, the perceptions of an astute student of the Filipino psyche, and the integrity and idealism of the man of conscience, and the result has been a class of journalism that is dramatic, insightful, memorable, and eminently readable.”

Among his many and various achievements, the novel “The Woman Who Had Two Navels” (1961) examines his country’s various heritages. “A Portrait of the Artist as Filipino” (1966), a celebrated play, attempts to reconcile historical events with dynamic change. “The Aquinos of Tarlac: An Essay on History as Three Generations” (1983) presents a biography of Benigno Aquino, the assassinated presidential candidate. The action of the novel “Cave and Shadows” (1983) occurs in the period of martial law under Ferdinand Marcos.

In 1996, he received the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature, and Creative Communication Arts, the highest honor for a writer in Asia. The citation honored him for “exploring the mysteries of the Filipino body and soul in sixty inspired years as a writer.” Accepting the award, Joaquin did not look back on past achievements but relished the moment, saying that indeed the good wine has been reserved for last and “the best is yet to be.” This, from a man who was about to turn eighty when he received the award.

A private person

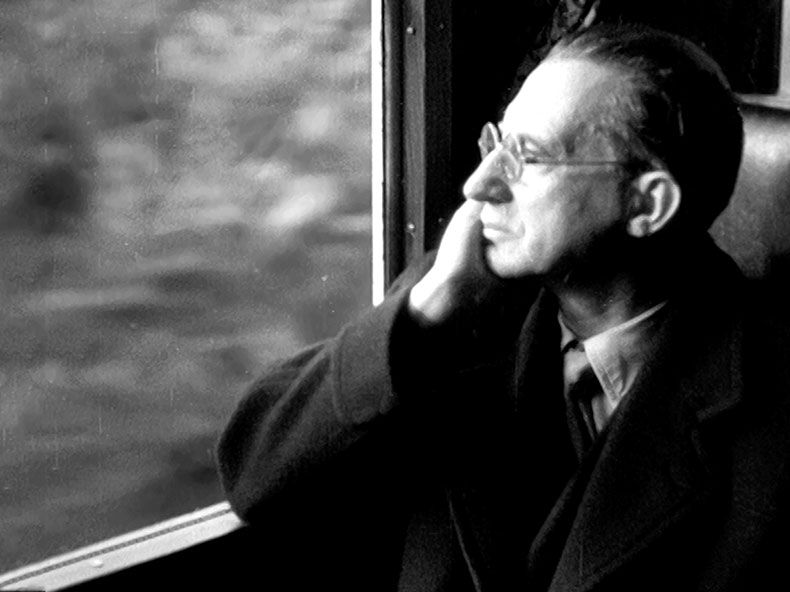

Engaged in a public profession, with a very public name, Nick Joaquin was a very private person. His reclusive character was formed early. He loved going out on long walks, simply dressed, shoes worn out from a great deal of walking (which helped him cogitate), observing the street life of the city, making the rounds of churches.

A person of habit, he wrote about himself : “I have no hobbies, no degrees; I belong to no party, club or association and I like long walks, my mother’s cooking and playing tres-siete. I don’t like fish, sports or having to dress up.” Though he gave strangers the impression of someone careless and even wild, Joaquín was a very disciplined writer.

Nick Joaquin, however, loved drinking. There is nobody else in Philippine history so closely identified with San Miguel beer, as him. He discovered that beer was a good “cover” because the alcohol relaxed him and helped him to overcome his shyness. Joaquin was capable of drinking an enormous amount of beer without getting drunk.

Joaquin’s intense shyness can be traced to his childhood. Of all his nine siblings, Nick was the most introverted and reflective, which was brought on by his nature as a writer: contemplative, introspective, deep. He never married and had a felt devotion for his mother, Doña Salome, with whom he lived up to the moment of her death.

He always treated his personal life with utmost dignity and discretion. He never talked about it. He channeled his energies to creative writing. His intense belief in Catholicism pervaded much of his work. He went to Mass and Communion with his mother daily, whenever he was free from other commitments, and prayed the rosary every day.

For the filipino identity

The problem of identity was central in Joaquín’s works. In an impressive body of literary, historical, and journalistic writings, Joaquín was a significant participant in the public discourse on “Filipino identity.” Already, this is present in La Naval de Manila which tells of a Manila religious celebration built on the tradition that the Blessed Virgin had miraculously intervened in the Spanish victory over a Dutch invasion fleet in 1646.

It sets forth a major theme Joaquín would develop in the years ahead: that the Filipino nation was formed in the matrix of Spanish colonialism and Catholic devotion and that it was important for Filipinos to appreciate their Spanish past. He wrote: “The content of our national destiny is ours to create but the basic form, the temper, the physiognomy, Spain created for us.”

This peaceful appreciation of the contribution of the Catholic religion did not blind Joaquin who wrote: “The Christian Filipino winces when he hears his country described as the only Christian nation in the Far East. He looks around, sees only greed, graft, vileness and violence. Questioning the value of religious instruction, he sneers, is this Christianity?”

As for his own writing, Joaquin’s response to the issue was more blunt: “Whether it is in Tagalog or English, because I am Filipino, every single line I write is in Filipino.” In a more jocular vein, he had written about how the local milieu was irrevocably present in his works: “I tell my readers that the best compliment they can pay me is to say that they smell adob0 (fish or meat usually marinated in a sauce containing vinegar and garlic, browned in fat, and simmered in the marinade) and lechón (roasted pig) when they read me. I was smelling adobo and lechon when I wrote me.” Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Nick Joaquín, the writer, was that his was always the voice of a deep, inclusive, and compassionate optimism in the Filipino.

When many of his contemporaries had long faded into the background, Joaquín continued to speak of his craft with the verve of a young writer. Well into his eighties, with close to sixty book titles to his name, he was working on more. He also continued to practice journalism and continued to contribute to various publications until his final days. When asked once if he ever intended to retire, Joaquín responded with typical mischief: “I’m not retiring and I’m not resigned.” Nick Joaquín lived in the city and country of his affections and continued to write until his death in April 2004 at the age of eighty-six.