The Second Vatican Council, held in Rome in 1962-1965, was a pivotal turning point in the Church’s 2,000-year history. Epitaphs by respected theologians have described the Council as “the most significant Church assembly of the twentieth century” and “the most important event in the history of the Roman Catholic Church since the Protestant Reformation” in the 1500’s. Saint Pope John XXIII (1958-1963), who called the Council, desired a profound aggiornamento (renewal, updating) of the entire Church.

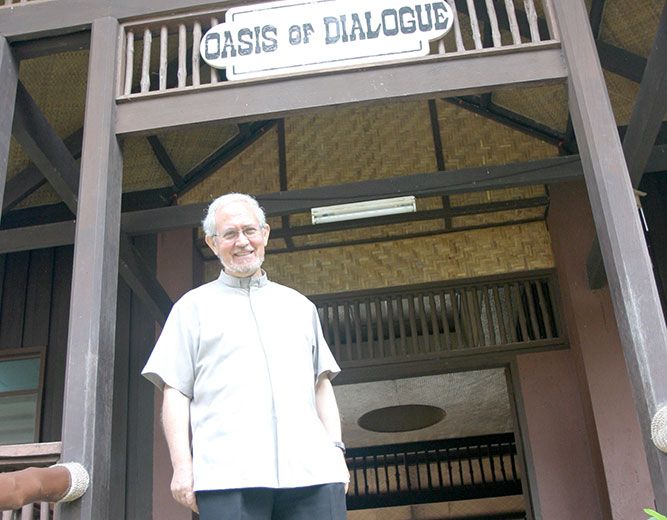

Saint Paul VI (1963-1978), who succeeded John XXIII and continued the Council, noted that the vision of the Church as a “community of dialogue” would be achieved as the Church entered into various dialogues on four levels: within the Catholic Church itself, with other Christians (ecumenism), with people of other living faiths (interreligious dialogue), and with the world and all its peoples. Paul VI himself described these four levels of dialogue as represented by four concentric circles.

It is enlightening to imagine these “four dialogues” as a series of four interconnected circles; there is a Vatican II document for each circle. The innermost circle is dialogue within the Catholic Church itself [Lumen Gentium (LG) = Church]. The next circle represents dialogue with other Christians [Unitatis Redintegratio (UR) = ecumenism]. The third circle shows dialogue with peoples who follow various world religions [Nostra Aetate (NA) = interfaith dialogue]. The largest, outermost circle symbolizes dialogue with the world and all peoples of goodwill [Gaudium et Spes (GS) = Church in the modern world]. This current presentation highlights one area of dialogue: ecumenical relations.

Understanding Ecumenism

Many Catholics have inadequate and often confused ideas about ecumenism.The term is derived biblically from two Greek terms: oikodome (the household of God) and oikomene (the whole inhabited world). Thus, ecumenism is directed toward the achievement of unity among all Christian churches and ultimately among all religious communities. Ecumenism envisions unceasing efforts to draw Christians together through the renewal of the churches in order to manifest the unity that Christ wills for His followers as well as for His one and only Church.

A brief glance at the two millennia of Christian history is helpful in appreciating our current reality. In the year 313 the Christian faith and the Church became legally recognized under the Roman Emperor, Constantine I. Then, in 380 Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire.

In 1054, the first great division occurred and the Church separated into the Orthodox Church in the East and the Roman Catholic Church in the West. Then, in the sixteenth century, the Protestant Reformation brought the next great division. Protestantism emerged with several strands: Lutherans, Calvinists, Anglicans, Baptists and numerous other denominations.

In recent decades, several significant efforts have been made to mitigate and heal these divisions. In 1960 Pope John XXIII established the Secretariat for the Promotion of Christian Unity in Rome. On January 6, 1964, Pope Paul VI and Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras of the Orthodox Church met on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem; they prayed together and exchanged the kiss of peace. On October 31, 2016, almost 500 years after Martin Luther’s protest, Pope Francis traveled to Sweden, met with prominent Lutherans, and urged atonement and Christian reconciliation. These are but a few significant steps on the long ecumenical road.

Ecumenism And Christian Unity

Pope John XXIII said that the unity of the Church was the “compelling motive” for his calling of the Second Vatican Council. When he spoke at the opening of the Council, he made it clear that he regarded the unity of Christians as a major concern of the Catholic Church: “The Catholic Church … considers it her duty to work actively so that there may be fulfilled the great mystery of that unity which Jesus Christ invoked with fervent prayer from His heavenly Father on the eve of His sacrifice.”

To promote his vision of ecumenism, John XXIII, as noted earlier, established the Secretariat for the Promotion of Christian Unity. Later on, John Paul II penned an entire encyclical on ecumenism (Ut Unum Sint, 1995). He noted: “It is absolutely clear that ecumenism, the movement promoting Christian unity, is not just some sort of ‘appendix’ which is added to the Church’s traditional activity. Rather, ecumenism is an organic part of her life and work, and consequently must pervade all that she is and does.” Indeed, ecumenical dialogue forms part of the renewed vision of being the Church today.

Insights From Vatican II

The Council rejected the view that the Church of Christ is to be identified “solely” with the Roman Catholic Church (RCC), with its implication that other Christians have no part in Christ’s Church. The Council Fathers spoke of the Church of Christ as “subsisting” [remaining, existing] in the RCC. “This Church, constituted and organized in the world as a society, subsists in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter … although many elements of sanctification and of truth can be found outside of her visible structures” (LG,8).

The clear implication is that all those elements that Christ willed for His Church are to be found in the RCC, but, nevertheless, Christ’s Church cannot be totally or solely identified with the RCC. Also, this certainly does not imply that the RCC always fully lives and uses these gifts to their best effect. Note that the Council was trying to balance the tendency to identify the one Church only with the Catholic Church.

Although this gift of “being Christ’s Church” is found in the Catholic Church, often “its members fail to live” by this ideal (UR, 4). “The Church, embracing sinners in her bosom, is at the same time holy and always in need of being purified, and incessantly pursues the path of penance and renewal” (LG, 8). She is simul justus et peccatur (both holy and sinful); her self-understanding is an ecclesia semper reformanda (Church always needing reform, conversion, and renewal).

Inter-Church Relationships

What is the connection between the RCC and other Churches? True, there are “splits in the garment of Christ”; this does not mean fragmentation into separate pieces. Restoration of unity has to be understood as the convergence of the RCC with other Christian Churches, not the return of other Christians to the Catholic Church. Thus, as shared gifts are rediscovered–in our own Church and in others–the unity desired by Christ for his Church will be realized (John, 17:21).

Clearly, the Council is doing a “balancing act,” asserting that the Catholic Church does not exclusively possess all the Lord’s gifts: “many elements of sanctification and truth are found outside its visible structure. These elements [Baptism, Eucharist, Scripture, faith, Holy Spirit, grace, deeds of Christian charity, prayer], as gifts belonging to the Church of Christ, are forces impelling toward catholic unity” (LG, 8); see UR, 3. We Christians really are in a fraternal relationship.

Additional Council Insights

These other Christian communities are validly termed: “churches,” “communities,” and “ecclesial communities” (cf. UR, 3, 4, 22). Why? They validly possess (in varying degrees) those elements which make the baptized a church, “and the Catholic Church embraces them as brothers, with respect and affection…for people who believe in Christ and have been truly baptized are in communion with the Catholic Church even though this communion is imperfect…. All who have been justified by faith in Baptism are members of Christ’s body and have a right to be called Christian” (UR, 3).

“The Spirit of Christ … uses them [ecclesial communities] as means of salvation” (UR, 3). “The Sacred Council exhorts all the Catholic faithful to recognize the signs of the times and to take an active and intelligent part in the work of ecumenism” (UR, 4).

The “sin of separation” has been jointly caused; “people of both sides were to blame” (UR, 3). “Such division openly contradicts the will of Christ, scandalizes the world, and damages the holy cause of preaching the Gospel to every creature” (UR, 1). “The children [Christians today] who are born into these Communities and who grow up believing in Christ cannot be accused of the sin involved in the separation” (UR, 3).

Practical Steps To Promote Ecumenism

One may cite various concrete steps that can foster the ecumenical movement: *avoid all negative stereotypes or false assumptions about other Christians; *encourage dialogues between leaders of various churches; *foster mutual projects that serve the poor and needy; *join in common prayer when appropriate; *commit oneself and your church to personal reform and self-renewal.

Additional “ecumenical” actions may include: *pray regularly for Church unity; *know your own faith well; *be willing to learn about other Christians and to personally know them; *cultivate a historical consciousness; *feel the scandal of divisions; *see the Holy Spirit’s action in others; *have biblical patience (also known as creative waiting).

Undoubtedly, significant ecumenical progress has been made under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Yet, many challenges still await the common commitment of all Christian churches. Veni, Sancte Spiritus! Come, Holy Spirit!