It was still early morning on May 24, but the sun was already up in the horizon in the southern Philippine city of Zamboanga. A group of about a hundred people – one or two bishops, several priests and nuns, a representative from the nunciature in Manila, and some foreign missionaries – were gathered at the port, waiting for a boat that would bring them to the nearby island of Basilan, once known as a hotbed of terrorism in the southern Philippine region of Mindanao.

After three hours on the slow boat, the visitors arrived in Isabela, the island province’s capital, where they took a bus to the nearby Catholic cathedral for the ordination and installation of a new bishop. A marching band of students from a nearby school and a crowd of Muslims and Christians gathered outside the church to welcome the visitors.

In his homily, Bishop Leo Dalmao of Basilan made special mention of “those who have died keeping their faith” in the province, the “poor farmers, fishermen, Muslims, Christians, tribal people who have died as victims of this senseless conflict.” And “to those of you who continue to stand firm in faith,” the new bishop offered his gratitude for the inspiration “to live on the peripheries of society.”

The prelate is no stranger to Basilan. As a Claretian missionary, he used to serve the Samal-Badjau tribal people, also known as the sea gypsies of Mindanao. A friend, Claretian priest Rhoel Gallardo, was killed in 2000 during his ordeal in the hands of the bandit Abu Sayyaf Group. Several other priests, nuns, and lay people have been abducted in Mindanao for years.

The relaxed atmosphere during the bishop’s installation was indeed surprising, considering that in February alone, at least 22 people died in twin explosions that rocked the Catholic cathedral in nearby Jolo in the middle of a Sunday Mass. The so-called Islamic State claimed responsibility for the attack.

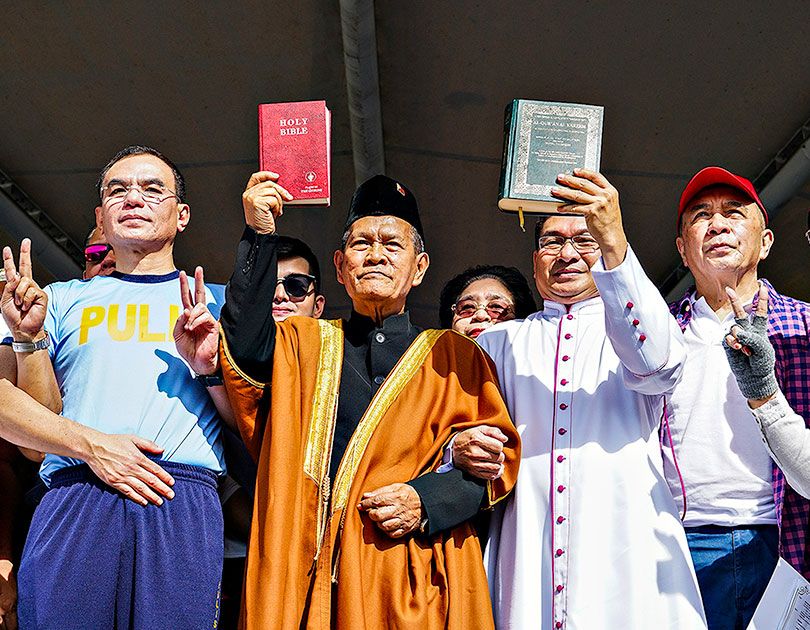

Religious leaders in Mindanao, both Muslim and Christian, have brushed off insinuations of religious animosity following the bombing. Several Muslim groups even went to the extent of surrounding and guarding Catholic churches during Sunday Masses to dramatize their solidarity with Christians.

“It is not a conflict between two religions” is the oft repeated response of religious leaders in Mindanao. The attacks on churches and the abductions of Christians are “political statements” of groups that are out to destroy the “harmonious relationship between Christians and Muslims.” Abductions were the work of criminal syndicates, both Muslim and Christian.

New Muslim Region

In January, residents of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao voted to ratify the Bangsamoro Organic Law, a legislation that aims to pave the way for the creation of a new and expanded Bangsamoro Autonomous Region.

The law was the result of a “comprehensive peace agreement” signed in 2014 between the Philippine government and the rebel Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), which, after demanding for independence, agreed to autonomy, recognition, and power sharing in the governance of the region.

The MILF, which broke away from the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) in the late 1970s, had been waging a protracted war in Mindanao, resulting in the death of at least 120,000 people and the displacement of many communities during the decades-long conflict. The MNLF entered into a peace agreement with the government in the mid-1990s.

The new organic law is a result of the conflicted rebellion in Mindanao. Father Calvo described it as “the mature fruit of a political process” that involved various stakeholders who envisioned a political framework to solve the reasons for the conflict. “It is basically the answer to the claim of self-determination that the Muslim community was demanding.”

The passage of the Bangsamoro Organic Law and the creation of the new autonomous region are not, however, magic pills that can instantly heal the wounds of years of misunderstanding, historical rivalries of tribal groups and sultanates, and cultural diversity in Mindanao.

In the January referendum, majority of the Tausugs in the province of Sulu voted against the ratification of the law, which they viewed as giving undue advantage to residents of mainland Mindanao, specifically those in the central part of the island, who belong to the Maranao and Maguindanao tribes. Reconciliation of the “individual visions” of the MILF, the MNLF, and other stakeholders on how the provisions of the new political entity be implemented is necessary.

A coalition of former rebels and incumbent officials form part of the Bangsamoro Transitional Authority before new regional leaders can be elected in 2022. Sultans and datus (rulers of tribal groups) will also act as advisers to the chief minister of the new region, especially when it comes to “conflict resolution.”

Trust is also a paramount issue that has to be addressed in an island that has been entangled in a cycle of violence for years. Political observers note that the demilitarization of the region is a challenging prospect because of “local trust deficits” stemming from memories of years of violence. Unless genuine dialogue is held and trust is built, the “demilitarization” of communities will be difficult.

The Challenge Of Extremism

Peace will continue to be a work in progress in Mindanao despite the ratification of the Bangsamoro Basic Law and the creation of the new Muslim region.

International Alert Philippines warned that the bombing of the Cathedral in Jolo “will not be the last tragic event in Muslim Mindanao as the entire region transitions from war to peace and from deprivation to development.”

The group rightly noted that the transition goes beyond the ratification of the organic law or the creation of the new Bangsamoro region. The target and the timing of the bomb explosions in Jolo showed that “a wedge is being driven between Muslims and Christians.”

“The death and destruction that came at Holy Mass in a Christian house of worship combines insult and injury to the longstanding, robust, and peaceful communion between Muslims and Christians in the island,” noted the International Alert Philippines report. “This is what violent extremism does,” it said.

“It creates fissures where there are none, and fractures inter-community relationships that make it easier to radicalize and recruit. It weaponizes religious and ethnic differences as a tool in destabilizing peace, including the sort of peace that the [Bangsamoro Organic Law] can bring,” it added.

All fingers again pointed at the Abu Sayyaf group and its many factions, whether connected to the so-called Islamic State or not, as “the greatest source of instability and continuing violence in the island,” if not in the whole region of Mindanao.

Violent extremism is not, however, exclusive to Mindanao. It has become universal and has been a resurgent problem around the globe. “Terrorism does not start or end with MILF,” wrote Matthew Bukit, program manager of Asian Vision Institute.

Bukit noted that “organizational instability, factionalism, and intersecting family and terrorist loyalties have perpetuated and intensified Mindanao’s kaleidoscope of terrorism, muddying already indistinct boundaries between myriad groups, cells, and factions.”

Mindanao has been witness to a long history of violence, from the anti-colonial struggles of the past to current movements that have been fueled by various groups, extremists or otherwise, that are trying to advance their political agenda.

Continuous Dialogue

There is no assurance that the creation of a new autonomous Muslim region will stop the activities of these groups, but it offers hope. It is a starting point, especially for the warring groups, which are now united as “partners” in peace-building under the new autonomous region.

Referring to the attack on the Cathedral in Jolo, Oblates missionary priest Roberto Layson said the challenge is “how to transcend our biases and prejudices” and to work together to build a “peaceful Mindanao despite all challenges that we are still facing.”

Continuous dialogue is the only way to stop the cycle of violence, distrust, and hatred that has ruled the region for many years. The recent political developments – the creation of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao – is an opportunity for both Muslims and Christians to continue the work of promoting harmony through dialogue.

Jose Torres Jr. writes for the Union of Catholic Asian News in Manila