His neighbors respectfully call him “uncle,” simply “uncle.” But along the countryside roads, as he relentlessly rides his bicycle, the most heard greeting is “Bob bhai,” that is, Brother Bob (bhai is Bengali for brother). The greeting is addressed to Father Bob McCahill, an American Maryknoll missionary who has been serving the Bangladeshi poor for 35 years.

For the last three years, he has been living in Narail, a town in the southwest part of the country, in the Khulna Division, 130 kilometers away from Dhaka. The fastest way to arrive there from the capital is by boarding at least six transportation means – 4 buses, a launch, a motorized river boat, a normal boat and an eight-seater auto rickshaw. In such a way, the distance is covered in about seven hours, if there are no hindrances or if one doesn’t doze off and miss the right stops and the connections. The normal bus takes longer, more than 9 hours, because of the long queue to board one of the ferries.

Ascetic lifestyle

The people’s greeting to Fr. Bob bhai defines the lifestyle of the unpretentious missionary. His house, a makeshift hut made of jute sticks over a foundation of clay soil, cost 3,000 takas (around US $45). The roof is reinforced with a polythane sheet to protect it from the rain. Like the huts of his neighbors, it is exposed to all kinds of insects and crawling animals. Venomous snakes, especially during the rainy season when they look for shelter in dry spots, are the most dangerous. But mosquitoes are the most common and unavoidable annoyance. During his sleeping hours, Fr. Bob can avail himself of a mosquito net. When he is out of bed, before and after sunset, he can count a bit on the repellent coils’ protection. But, to a certain extent, he has to stoically put up with the mosquitoes’ bites and face the ever present threat of dengue fever.

The small hut’s size (3 x 2.5 meters) can easily keep the few things the missionary needs. A wooden double-deck bed made to accommodate any eventual visitor and the seminarians who have been staying with him for their month-long yearly pastoral experience. The other existent piece of furniture is a low stool on which Fr. Bob sits to pray, read or write. If a visitor comes along, he may ask for a chair from the nearest neighbors. There’s also a little shelf to keep a few essential books far from the reach of the mice; a one burner kerosene stove; a so-called hurricane lamp; and a pail of water. The residual food supplies (rice or bread) hang from the roof in plastic bags as a means to prevent the mice from sharing it. The hut also shelters his bicycle during the night.

There’s no table, no clothes cupboard in the tiny dwelling (the bed’s upper deck serves as a storing place most of the year when no guest is around); the bed has neither a mattress nor pillows. Besides, there’s no electricity. Therefore, there’s nothing moved by such energy, like TV, radio, fridge, or fan. Fr. Bob doesn’t care about such commodities of convenience. And, seemingly, he doesn’t miss them. He doesn’t have even the ever more present and pervasive mobile phone. For his most needed calls, mainly to set medical appointments for the patients he is helping, he uses the phones of the nearby shops. He feels comfortable and happy with very little.

The hut’s security is… its poverty and almost emptiness. And the neighbors watch over it. The lock, used when he is away, wouldn’t prevent a burglar from breaking in. But, a thief would find very little to carry away, besides the bicycle. The Father’s clothes are rather worn out and toiletries are non-existent. He doesn’t use shampoo, aftershave or any body lotion. Only someone uninformed or completely desperate would try to break in to steal.

The toilet is a small pit hole three meters from the hut, also made of jute sticks and with a cloth curtain instead of a door. Toilet paper is not used. Hygiene is kept with a little plastic jug of water like other people do. He drinks water from a nearby well and bathes at another, like all Bangladeshis do.

Is it necessary to live so simply? His answer: “It is necessary for me. I am doing what God moves me to do. I am not going to legislate or suggest it to others. The simpler we live, the better we serve. The simpler we live, the more we are like the people living around us.”

Itinerant Good Samaritan

Father Bob’s day starts very early. He gets out of bed at 3.30 a.m. for a full hour of prayer, followed by daily Mass. He never misses to celebrate it, except, as he says, on Holy Friday when Masses are not celebrated. When Muslim muezins call for prayer towards 5 a.m., through the powerful loudspeakers, Fr. Bob has already finished meditation. Then, he does his personal hygiene while it is still pitch dark – only years of experience prevent him from cutting himself and damaging the moustache’s shape while shaving – prepares and takes some breakfast, performs the little house chores and sets the program for the day. Around 6.30, he is ready to hit the road on his Chinese bicycle that takes him to many district villages to meet and help the sick, especially children, to overcome infirmities and deformities.

In his excursions, he pedals tens of miles daily in a seemingly effortless manner. But he stresses that what he does is to sweat for the poor, to show them the love and compassion of Jesus. At the age of 73, he keeps extremely fit. Most of the other days, he pedals 20, 30 and even 40 kilometers. Once a month, at least, he takes a long ride: a round trip takes him 70 kilometers or so. Lawrence Kollol Rozario, 35, a seminarian from Dhaka who did his pastoral experience with Fr. Bob at the beginning of this year, says that he is “a Good Samaritan for the poor.”

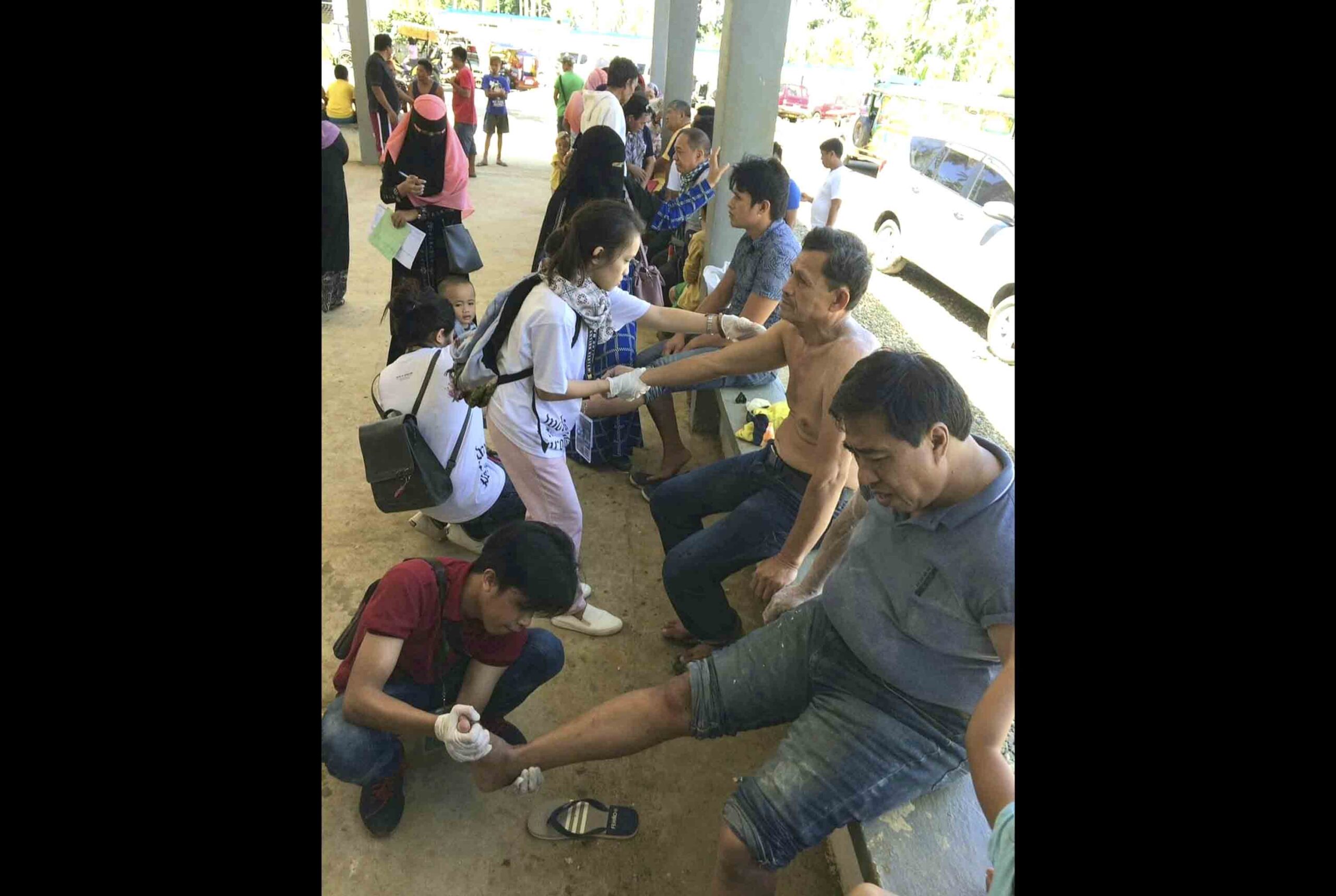

Some common defects he finds in rural areas are cleft lip and cleft palate. Both disfigure the infants and interfere with eating and speech. Other problems he addresses are burn contractures, hernias, and club feet which operation can only be done in Dhaka. Generally, he gives priority to children and young people to enable them to enjoy a happier life. The operations are shouldered by foreign donors. For instance, the harelip and cleft palate surgery to children in need are paid for by an American charity called Smile Train. A number of doctors and hospitals cooperate with him, collaborating in a work of dedication to the sick.

Returning from the villages, he stops at the local library to read the papers and get acquainted with the country’s and world’s news. Sometimes he is the one collecting the papers from the local distributor and delivering them to the library, reminiscent of his youth as a paperboy.

On his way home, he stops at the local bazaar to buy the daily portion of vegetables, bananas and bread for breakfast. He buys duck eggs from a faithful Muslim shopkeeper near his hut.

For his personal expenses, he just uses money that comes from his extended family – brothers, sisters and cousins… He lives on a small budget.

Arriving home, in a neighborhood on the periphery of town, he puts on his loongi or lungi, a garment sewn into a tube shape like a skirt, worn around the waist and tied generally with a simple “double twist” knot. The most commonly-seen dress of Bangladeshi men is Fr. Bob’s dress while at home. But, for the sake of practicality, he wears pants, and not a loongi, while bicycling.

His own chef

Fr. Bob has reached a great degree of kenosis – self-forgetfulness, self-emptiness and self-giving. After a long and sweaty bicycle ride, he drinks several glasses of tubewell water to compensate for the dehydration of the morning. Somebody less ascetic would look for some rest and even enjoy a cool drink; but he just proceeds to perform the house chores as if no effort had been made. He can do without worldly pleasures. Anyway, to abstain from alcoholic drinks is part of his Christian witness, because Muslims assume that Christians drink!

He prepares the vegetables for the evening meal – the real one, because, at lunch time, he just eats a snack. The operation is closely “monitored” by the neighbors who keep coming to ask questions and, especially, to check on him. If he is not rightly in front of the door, but on the “kitchen corner” of the “mansion,” they peer inquisitively inside to see what he is doing. After three years, he keeps being a source of curiosity, starting from his meals: they certainly find it strange that he never cooks any fish or meat. He lives as do the poor around him. He admits, regarding the food: “I eat the same kind of food all the time. They wouldn’t be pleased to eat the same kind of food I am eating, kichuri, (a stew) because that’s something they enjoy once in a while and I eat it every day.”

Before or after preparing the rice and vegetables, he sweeps the hut and the ground in front of it since the lengths of bamboo which shade the hut are always dropping dead leaves. Then, he goes to the well to bathe, often closely observed by curious neighbors and passersby. There, too, he does his laundry. Modesty is preserved by wearing the traditional loongi. Then, he still has the time to attend to some duties and to do some reading. He keeps track of the birth dates of fellow priests and brothers in Bangladesh. He writes and sends out weekly between ten and twenty letters.

Before dusk, he cooks the evening meal, made up of rice and veggies and with bananas for dessert. Since he has only a small stove, the spinach is cooked in a polythane bag separated from the rice. No oil is used, just salt and a local powder flavor to mix in the rice after it is cooked. He chows it down seated on the stool or on the straw mat, often under the ever present lady neighbors’ observation.

After supper, he scrubs the blackened pot, does the washing up and reads, even though there’s no silence because the neighbors keep on talking loudly. Doing it daily with the help of the kerosene lamp is an exercise in persistence.

Weekend in the city jungle

On Friday evening, Fr. Bob moves to Dhaka in the company of the sick due for treatment along with their relatives. The rather dirty and worn out bus travels overnight. Its scheduled departure from Narail is 8.30 p.m. Often, it departs late. It has to cross two rivers. Due to the lack of ferries, the bus may queue for 2 to 10 hours. Hardly can it make it to Dhaka in less than 10 hours, in spite of the passengers’ requests for the driver to increase the speed. Sleeping is extremely difficult, especially because of the persistent insects and disturbing horning.

Arriving in Dhaka almost sleepless, Fr. Bob has to find his way in the very noisy – even deafening – traffic confusion of bicycles (single, pulling carts and rickshaws), tricycles, cabs and baby-cabs, cars, bigger and smaller buses and more. Aggressive and reckless driving is seen everywhere. Even though road accidents are rare, all the buses are badly scratched. Traffic disputes often end in quarrels. There are many other reasons for verbal altercation and loud ruckus – one of the aspects of Bangladeshi assertiveness and the quest for personal rights. However, quarrels, unlike in other places, do not end up in brawls. Bengalis usually just face one another in heated exchanges.

Fr. Bob has often to struggle to manage to get the children with their mothers and their belongings – space taking – inside the city buses. After ensuring their admission in hospitals for surgery, he checks on the sick brought there previous weeks or even months and undergoing treatment. He spends part of his weekend running from hospital to hospital, meeting patients, nurses and doctors.

Experience and the steady consultation of the indispensable The Merck Manual of Medical Information, has taught him a lot about diseases, as the case of little Jamila, a 4-year-old girl shows. Her mother came to ask for help while he was in Malidanga village. As common procedure, Fr. Bob asked her to bring the girl to the local hospital. There, they were told to get a CT scan. They did, but it was inconclusive. Nevertheless, the hospital was going to go ahead and give her a blood transfusion. The local doctor’s diagnosis was mild hepatomegaly (an enlarged liver). Father Bob suspected she had nephretic syndrome, a kidney disorder. And knowing that any blood collected locally is not checked to ensure, for instance, that it is HIV-free, he offered the parents the chance of taking her to Dhaka, to the National Children’s Hospital for a thorough investigation. Dhaka’s more accurate analyses confirmed Father’s suspicion. But she could be admitted only on Saturday. So, as happens quite often with others, he had to find accommodation for the child and her mother and, in another location, for the girl’s grandfather who was accompanying them.

Sharing his reflections

Besides caring for all his patients, Fr. Bob has many other things to do in Dhaka. He doesn’t relax. The call of duty is pressing and his pace is always accelerated. Wearing slippers and with his strap bag hanging from the shoulder, he goes around on the buses and, sometimes, riding rickshaws, after bargaining the price. An unavoidable stop is at the Post Office, to collect his mail and send away many letters he has been writing during the spare moments, like those while awaiting for the bus in Narail.

Monthly, he photocopies and posts his interesting diary. Everyday, he tries to catch something that’s a little bit unusual, out of the ordinary or memorable. He takes some rough notes about it. At the end of the week, when he gets to a typewriter, he writes down those notes more formally. Then, at the end of the month, he compiles all these things and forwards them to Maryknoll (from where copies are sent to his sister and brother) and a few friends. He explains its purpose: “The main reason for writing a journal is to keep me aware of what is happening. I don’t want to go through life without reflecting on what I am seeing. It is supposed to be something that keeps me a little bit keen on what is happening around me and on what I am doing here. And it is appreciated stateside, therefore, I like to do something that is helpful to people.”

Saturday nights he spends in a room in Bacha English Medium School, run by the Maryknoll Sisters – Sr. Miriam Perlewitz and Sr. Joan Westhues – where more than 800 eager children of the neighborhood are taught values, educated and prepared for life.

A priest-servant

Life is mission and mission is life for Fr. Bob. Not only does he live for the poor, he lives like the poor he serves. The way he lives and what he is doing give him inner peace. Because he thinks it is the right thing. He doesn’t do it to be appreciated. He was called to do it. A call that matured through prayer and commitment. He is a living Gospel for those he serves. His life is a sign of God’s loving care, especially for those who are sick.

He started off his missionary life in the Philippines. After eleven stimulating and happy years there, he offered to work in Bangladesh. “The idea of coming to Bangladesh was that of being a priest-servant,” he states. In a country prone to natural disasters – tidal waves, famines, floods, war, everything – he wanted to give his little contribution to alleviate people’s sufferings. “I told myself: ‘I am going there hoping to do something for those people. I don’t know what I can do, but I’d like to go there for the sake of the poor.”

The fact that Bangladesh is a Muslim country was secondary in his decision. But, soon, he did see the advantage and he deliberately stresses it: “The fact that Bangladesh is an Islamic country is a big bonus, because in doing the one – serving the poor – we are also doing the other – serving the Muslims. And it has a great meaning for them because they have the saying that ‘by serving the poor, we serve Allah.’”

It was from the Holy Spirit

At the beginning of assignment by Maryknoll to Bangladesh in 1975, Fr. Bob and his four companions enrolled in a language school for one full year. Bengali is a Sanskritic language. “The alphabet is very funny, but there are no tones. I don’t think that it is as difficult as Korean, Japanese or Chinese,” says the missionary.

In December 1976, after getting out of the language school, the five missionaries decided to look around for a while to find out how they could be more useful to people. Then they set an appointment with the late Archbishop of Dhaka, Msgr. Theotonius Amal Ganguly, who had invited them to Bangladesh. Fr. Bob recalls the meeting: “We told him: ‘During this year, we have been looking around and praying and we have decided that we want to work with Muslims. Please let it be.’ The Archbishop told us: ‘Go ahead and try it, because what you want to do may be from the Holy Spirit.’”

God was pulling the strings

Having received that permission, Fr. Bob went to Tangail, a town 60 miles northwest of Dhaka. There were no Christians there. After 10 months in other places, the other colleagues joined him. Meanwhile, they had decided that it would be the place to work as a community.

Interesting is how he got into Tangail. He recalls the episode: “I just got on a bus from Dhaka with a small bag of things. I had no idea where I was going to be by evening. Fifty-five miles away from Dhaka and almost five miles to Tangail, the fellow on the seat next to me – with whom I had not been conversing – just turned to me and asked: ‘Where are you going?’ I answered: ‘I don’t know.’ He said: ‘Come with me.’ At that point, I understood immediately that this was God, God was pulling the strings there.”

That man went with him to a neighborhood in Tangail in which a famous spiritual guide was living. He met his son who was also a spiritual guide. While talking, the spiritual guide asked Bob where he would be staying. Fr. Bob replied: “I don’t know. I don’t have any place.” Then the guide called one of the disciples of his father and told him: “Mojammel, take this fellow with you and let him live with you.” Mojammel took Fr. Bob to his house where he stayed with him and his family for six weeks. Meanwhile, Fr. Bob got a place to rent and things worked out. He recognized immediately that God was at work in the choice of the place: “God took care and inserted me in Tangail.”

The five missionaries stayed in Tangail for nine years. Then, Fr. Douglas Venne decided to go to the farm to which he had previously commuted, in order to be closer to the people. Later on, when Fr. Douglas got less able to do the farming, he started adult education for small groups of women, educating them in their language. And he was also taking care of the sick poor in that village and helping them to get treatment. Bob took that opportunity to move to another district. So, he went to Kishoreganj, a place recommended by a doctor whom he knew, because its inhabitants had what he defined as “fellow feeling.”

Evangelizer, not proselytizer

Fr. Bob thought he might be in Kishoreganj for another 10 years. But, after he had been there for almost two, he understood that it would be enough to be there for three years because, by then, the sign would have been accepted. Which sign? “That” – he explains – “the Christian missionary is not simply the one who comes to convert. A Christian missionary comes to be a sign of love for all people and respect for their religions. We want nothing but betterment. If all they want from us is better health, that’s all we’ll try to give them. I am not here to push anything down anybody’s throat. I am not a proselytizer, I am an evangelizer. I wish to make known the sign of Christ’s love for all humankind, I am evangelizing.”

Many Bengali Muslims regard various Christian missionary programs as means that are being used to convert them, which also means missionaries lack respect for their religion. Therefore, Fr. Bob notes: “The act of love is itself evangelization, especially among these people whose very strong suspicion is that a missionary comes to convert them and uses healthcare, education and social development to that end. We must show them complete unselfishness. We are here to show these people love and respect, and leave them in a way that will allow them to do the same while remaining Muslims. God is not unknown to Muslims. They resonate very powerfully with what we are doing, that is, loving.”

Like Mahatma Gandhi

According to Bob, the Mahatma Gandhi – he resembles him more and more – had a good insight to give to Christian missionaries in his newspaper column in Young India, where he calls on different groups of people. One of the groups he was most interested in was Christian missionaries, because, quite clearly, he didn’t think that missionaries were doing the mission of Jesus. Fr. Bob notes: “He didn’t read Jesus in the way some Christians read Jesus. He read Jesus as the One who came to show the love of God for all people. And his advice for Christian missionaries was to lead a life of service and of utmost simplicity.”

Fr. Bob agrees with Gandhi’s words and makes them his own: “It is indeed the best preaching. If we want to touch the hearts of people of this Indian subcontinent – that now is India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka (at that time, it was only India) – we have to live a life of service to them, living simply among them. This would be efficacious, effective, real Christian mission showing them the Jesus that has not been perceived by many.”

He goes on to say that Christian missionaries should not emphasize the conversion of Muslims. They should be anxious “to be in love with humankind, to be servants of humankind, to be witnesses of Jesus in the world. And let God take care of the conversions or the non-conversions – whatever God chooses.” This is the difference between proselytizing and evangelizing.

What is the purpose of life?

People are very curious about Fr. Bob and ask him many questions. Wherever he goes. Often about his salary. He tells them: “I don’t have a salary. I don’t work for any NGO, agency or the government. I receive money from my own brothers and sisters, my own extended family. It is their money that I use in my work here. I tell the people that it is not a matter of money, it is a matter of the heart, a matter of love. The people I am helping, I help them because of the love of God. That is the way Jesus operated. In the Acts of the Apostles 10:38, Jesus is described in the most succinct description of His life and apostolate: Jesus went about doing good and healing. That is what I try to do. I try to use that model for what I am doing here.”

He thinks that people do listen to what he has to say about Christianity. But he also thinks that there’s no need to be preaching to people about Jesus. If they ask him, of course he tells them. He is not afraid of talking about Jesus. He mentions Jesus every day as the One who was going about doing good and healing, and as the reason of his missionary service, going around on his bicycle doing some good, helping those kids to get healed. That should be clear to people that following the teaching of Jesus leads to be like Him, loving all humankind.

But he loves challenging people to think. “I always ask people: ‘What is the purpose of life?’ They just look at me. Then I say: Christians believe that the purpose of life is love. This is striking for a Muslim, because they also believe in love but they never really thought that the purpose of life is love. Occasionally, a sign is seen in public places, saying: “Prayer is the key to heaven.” And I tell them: ‘Prayer is very good, very essential but, for Christians, prayer is not the only key to heaven. Love, exercised in a number of ways for our fellow people, is the key.’”

Fr. Bob is open with people and he doesn’t hide his feelings. One day, he was speaking to a very religious Muslim on the bus who asked him if he had ever read the Kur’an. Bob answered: “Yes, I read completely the Kur’an in translation, not in the original Arabic.” He kept asking what he thought of it. Fr. Bob replied: “I understand a bit more of your religion, but to be frank with you, the Kur’an doesn’t thrill me. I am interested and I am happy for having read it to understand what it is. It inspires many, many Muslims, but it is not the kind of thing that inspires me.” Fr. Bob recalls: “He was disappointed to hear that. They need to know the truth. Because most Muslims believe that after reading the Kur’an you are hooked on it. They don’t seem to realize that people have different attitudes and backgrounds. They need honest partners in dialogue.”

Sweating for the people

Sometimes people tell Fr. Bob: “You would like to have people following you and doing this kind of good work, but they will never follow you unless you become a Muslim.” He answers: “Well, there’s no chance of that happening. And if we can’t learn from people of other faiths, from their virtue, from their good works, something we can do even while practicing another religion, then we are in a pitiable condition.”

According to the official Church teaching, Fr. Bob is engaged in a kind of dialogue – witness of life, dialogue of life in the presence of people of another great faith. But, he explains that he doesn’t particularly like the word dialogue, because it normally connotes sitting around drinking tea and conversing. That’s not what he is doing, even though he does sit down and has good talks: “What I am doing is sweating for the people. I am going out to the people at a distance, I don’t just walk around the town. I am not satisfied in staying in town. The town is my base because there’s transportation to take people to hospitals which are 130 kilometers away, or 8 hours away. Dialogue is mission in this context. Our Christian lives is what Muslims need to see.”

And he stresses: “Jesus lived a life of service: He didn’t come to be served, but to serve. And, to show that, He washed His disciples’ feet. Anyone who says that he loves his neighbor and doesn’t take care of his needs is a hypocrite. So I came here to be a Christian. I think that being a Christian in Bangladesh is mission. Christian and mission are synonymous. One who tries to live his Christian life in Bangladesh is doing mission; he is giving the witness a Christian is supposed to give. With God, we love all people.”

Time to move

When he first goes to live in a new location, the most difficult moments occur because nobody knows him or the program he has – to help sick kids for free. But, after a while, people hear about it and they recommend to him kids he should see. So, he goes out to talk to the children’s parents. At the beginning, lots of times people promise to go with him but, then, they don’t go, they stand him up. Slowly, slowly a number of people do accept his offer to accompany them to professional help in Dhaka where the best hospitals are, the best treatment is available.

From experience, three years is the time needed to pass his message of love and respect. It takes Fr. Bob a good year to break the suspicion of people. In the second year, their trust grows. By the third year, affection for him begins to show. So, by the end of the third year, Fr. Bob is free to leave. He can go, because he has dispelled the suspicion of the people in that area. He has convinced them that it is possible for a Christian missionary to love Muslims and not demand their conversion to another faith.

At the suggestion of the local bishop, Fr. Bob will soon choose a new town as his base to continue his ministry of friendship and healing among Muslims.

About this experience of inculturation among Muslims, one can read Father Bob McCahill’s book Dialogue of Life: A Christian Among Allah’s Poor (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1996. Pp. 109, reprinted in Manila by the Claretian Publications).