Pope Francis noted that we do not lack solutions: What we lack is any political will to address this crisis. Only a few months after the pope published Laudato Si in 2015, 196 countries adopted the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) by the end of the century.

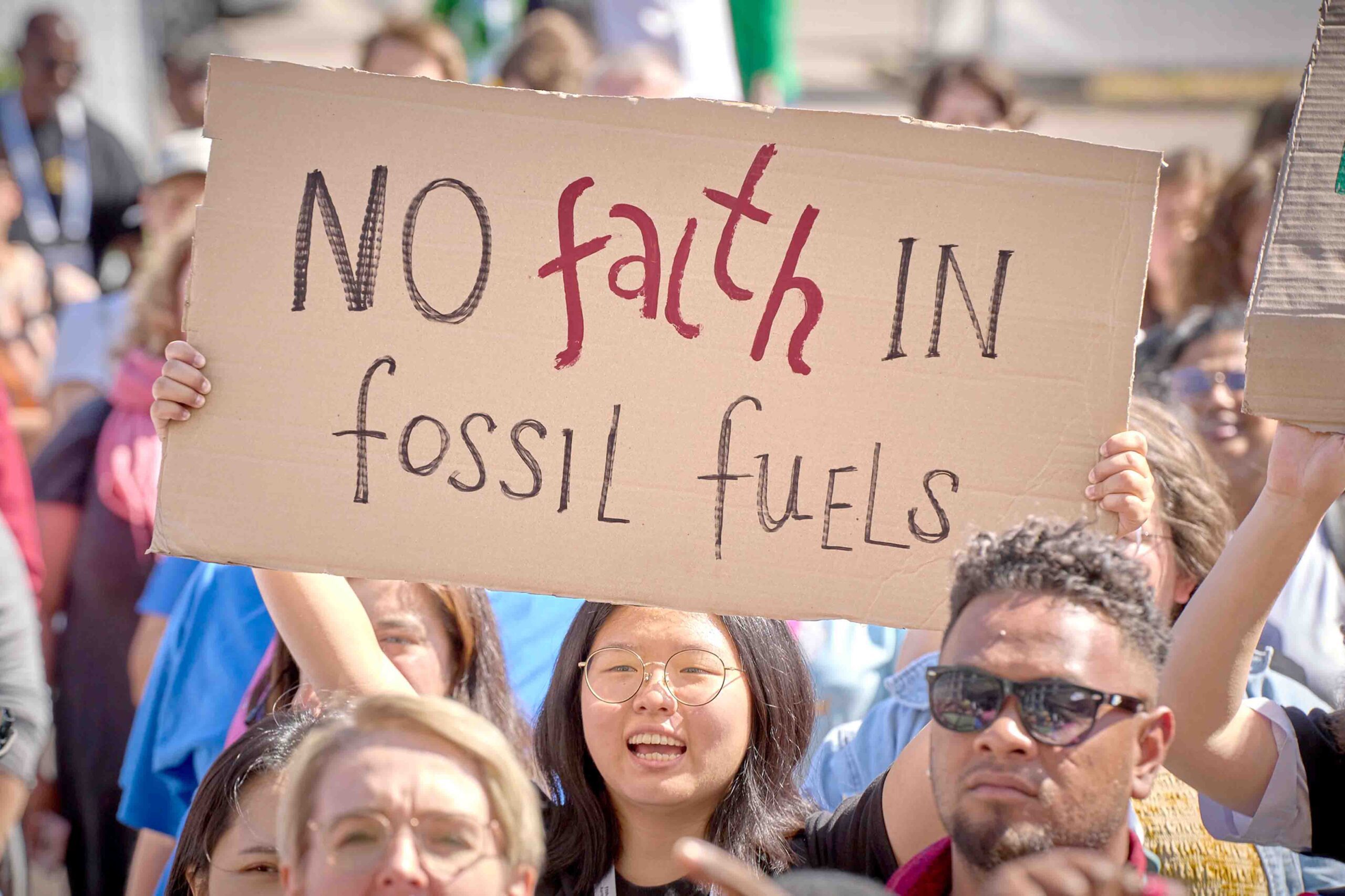

To reach that goal, the world’s industrialized nations would have to work together to stop the growth in greenhouse gas emissions by 2025. But eight years later, we are still not on track. The Financial Times estimates signatory nations have committed less than a fifth of the estimated $4 trillion needed to achieve the Paris Agreement’s goals. All the while, ecological disasters increase in number and scope every year.

The pope writes in Laudate Deum, “I feel obliged to make these clarifications, which may appear obvious, because of certain dismissive and scarcely reasonable opinions that I encounter, even within the Catholic Church” (n. 14). More than 40 percent of U.S. Catholics reject the idea that human beings are responsible for climate change, according to a 2023 Pew Research survey; many also shrug and say, “There’s nothing to be done”–a sentiment rarely expressed on issues like abortion or immigration.

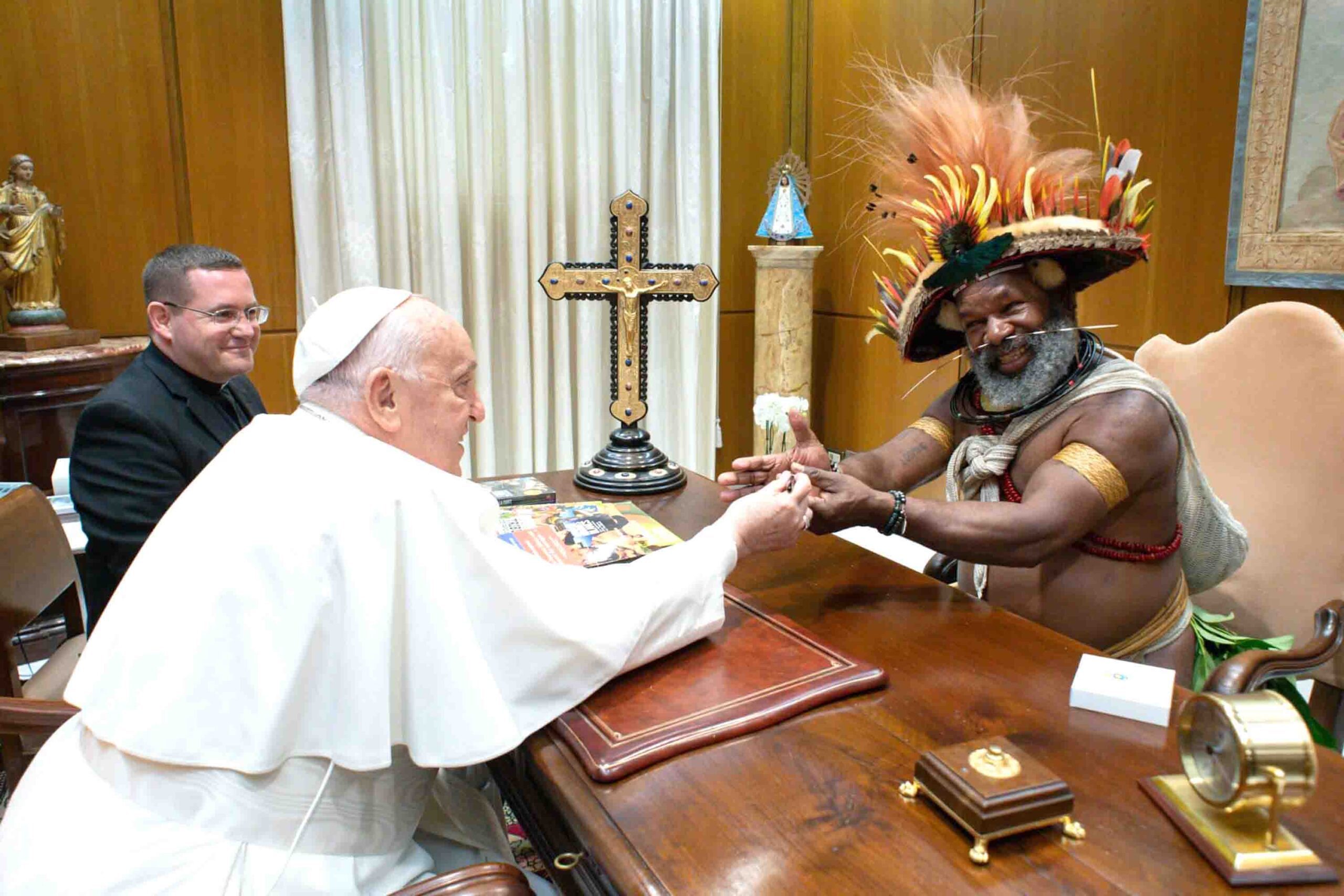

Laudato Si did not only address the overwhelming data showing the scope and effects of climate change but also stressed the moral dimension of caring for our common home. Pope Francis grounded his analysis in integral ecology, presenting climate change as more than merely a technical or scientific problem; it is also profoundly human.

Francis reminds us in Laudate Deum of two convictions he repeats frequently: “Everything is connected” and “No one is saved alone.” He reminds us that even in the face of such intractable challenges, we have to work not only toward better policies and more effective implementation but also toward greater solidarity: “To say that there is nothing to hope for would be suicidal, for it would mean exposing all humanity, especially the poorest, to the worst impacts of climate change” (n. 53). It is only by renewing our hope that a better world is indeed possible that we can begin to build it.

HUMAN DIGNITY

For Francis, care for our common home is also an issue of human dignity. He calls for the conversion of our “throwaway culture,” in which anything fragile is crushed under the weight of the deified market. That economic system is amoral, if not immoral, only concerned with feeding itself and progress for progress’s sake. Francis points to this cultural myopia as the central sin of the climate crisis: “When we fail to acknowledge as part of reality the worth of a poor person, a human embryo, a person with disabilities…it becomes difficult to hear the cry of nature itself” (Laudato Si, n. 117).

Francis offers the church as an interlocutor in the scientific and political conversation, suggesting a moral vision to a society dominated by a technocratic paradigm centered on profit, power, and growth at all costs. He writes in Laudate Deum: “Let us stop thinking, then, of human beings as autonomous, omnipotent and limitless, and begin to think of ourselves differently, in a humbler but more fruitful way” (n. 68).

SCIENCE AND THEOLOGY

Laudato Si and Laudate Deum” are remarkably deft in integrating science and theology. Pope Francis takes up the Second Vatican Council’s charge for the church to read the signs of the times and interpret them in light of the Gospel. If we are to care for our common home, we cannot stand by amid ecological devastation that threatens the grandeur of God’s creation and human livelihood. We must act.

Pope Francis closes Laudate Deum by using the United States as an example of how the reality of interconnection demands particular conversion from some. Because “emissions per individual in the United States are about two times greater than those of individuals living in China, and about seven times greater than the average of the poorest countries,” he writes, “we can state that a broad change in the irresponsible lifestyle connected with the Western model would have a significant long-term impact” (n. 72).

Pope Francis’ choice to publish Laudate Deum at all is striking. If a follow-up is made to an encyclical, it is usually not done until decades later (see Quadragesimo Anno, published 40 years after Rerum Novarum). For this exhortation to be published a mere eight years after Laudato Si underscores the pressing reality: We are running out of time to act on the climate crisis.

For too long, we have paid for our lifestyle with a kind of ecological credit, watching the seas rise and the gasses accumulate in the atmosphere with the sinking feeling that soon, the bill will come due. It is due. Published in America Magazine