I would like to suggest that the first concept to grasp about genetic engineering is that, in and of itself, it is neither good nor bad. It is technology that allows us to insert genes from one genome (the complete set of genes or genetic material present in a cell or organism) into another genome. In other words, it is simply technological ability.

Second, we need to agree that when referring to ‘genetic engineering’ in this article, we are discussing only the specific and narrow application of the term in regard to gene manipulation, rather than time-honored practices of managed breeding and hybridization.

Third, nature has mechanisms that, under certain rare circumstances, have allowed genes to ‘flow’ from one species to another species. This is effected by viruses that invade cells of plants or animals and, especially, microorganisms. It is supposed that, most often, these situations result in death or dysfunction of the host organism. In rare cases, the organism survives and the new genetic information becomes a part of the host’s genetic sequence. This, then, is passed on to subsequent generations. These natural phenomena, in part, led the research into developing ‘genetic engineering’ technologies. However, the natural process is, in many ways, a dramatically different event from that practiced by ‘genetic engineers.’

Fourth, there has been a tremendous volume of rhetoric in public media devoted to smudging common language used to describe life processes as most widely understood. One result is that it has become very easy to divert a conversation away from a discussion of genetic engineering to weeds of semantic debate. This often frustrates and inflames the emotions of those participating in the discussion and tends to result in anger and disengagement from the discussion.

We will touch on some of the semantic arguments that are being used to obscure the impact of genetic engineering a bit further on.

STARTING AT THE BEGINNING

There has been much discussion of late that tries to recast traditional methods of plant and animal reproductive management as ‘genetic engineering.’ Before the concept of genetics was formalized, herdsmen and farmers alike, through observation, trial and error, learned to select the ideal specimens of plants and animals for use as ‘seed stock’ and ‘breeding stock’. Over time, curiosity regarding this practice led to ‘scientific’ discovery. Through the insight and discipline of early researchers such as Gregor Mendel who, around 1863, discovered that traits are transmitted from parent to child by specific cell components, later called genes , the concept of genetics was introduced.

The pace of scientific discovery escalated along with the technological advances that permitted and supported such discoveries. The list below shows the rate of development increasing as technology and information sharing in the electronic age gained speed.

To name a few:

– The 1879 discovery by Fleming of chromatin, later called chromosomes.

– In 1906, William Bateson proposed using the term ‘genetics’, “which sufficiently indicates that our labors are devoted to the elucidation of the phenomena of heredity and variation: in other words, to the physiology of descent, with implied bearing on the theoretical problems of the evolutionist and the systematist, and application to the practical problems of breeders, whether of animals or plants.”

– 1915, bacterial viruses were discovered,

– 1920, Evans and Long discovered the human growth hormone.

– 1940, Oswald Avery demonstrated that DNA is the transforming material of genes.

– 1946, the discovery that genetic material from viruses can be combined to form distinct and new viruses – genetic recombination.

– 1950, artificial insemination was developed and successfully completed.

– 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick described the double helix structure of DNA in the publication, Nature, ushering in the modern age of genetics

– 1960, hybrid DNA – RNA molecules were created.

– 1966, the genetic code was cracked.

– 1969, the first synthesized enzyme was created in vitro.

– 1970, The first complete synthesized gene was produced.

– 1973, Stanley Cohen and Herbert Boyer perfected genetic engineering techniques to cut and paste DNA (using restriction enzymes and ligases) and reproduced the new DNA in bacteria.

– 1978, recombinant human insulin was first produced. North Carolina scientists showed it was possible to introduce specific mutations at specific sites in a DNA molecule.

– 1980, the Supreme Court in Diamond v. Chakrabarty approved the principle of patenting genetically-engineered life forms that allowed the Exon oil company to patent an oil-eating microorganism.

– 1981, the first transgenic animals were produced by transferring genes from other animals into mice.

– 1981,the golden carp was the first fish cloned by Chinese scientists.

– 1983, the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) technique was conceived. PCR, which used heat and enzymes to make unlimited copies of genes and gene fragments, later became a major tool in biotech research and product development worldwide.

– 1984, the first genetically-engineered vaccine was developed. The entire genome of the HIV virus was cloned and sequenced.

– 1985, genetically-engineered plants resistant to insects; viruses and bacteria were field tested for the first time.

– 1986, the EPA approved the release of the first genetically-engineered crop- gene-altered tobacco plants and authorizes field-testing.

– 1987, the first authorized field tests of engineered bacterium ‘Frostban’ were performed in California on potatoes and strawberries.

– 1990, Chy-Max(tm), an artificially-produced form of chymosin, an enzyme for cheese making, was introduced. It was the first product of recombinant DNA technology in the U.S. food supply.

* The first successful field trial of genetically-engineered cotton plants was conducted.

* The plants had been engineered to withstand use of the herbicide Bromoxynil.

* The first transgenic dairy cow – used to produce human milk proteins for infant formula – was created.

– 1993, FDA declared that genetically-engineered foods were “not inherently dangerous” and did not require special regulation.

– Subsequently, several hundred patents have been awarded for genetically-altered bacteria and plants.

For all intents and purposes, traditional breeding was not generally considered as ‘genetic engineering’ so much as sound agricultural management. Technologies, such as artificial insemination, in vitro fertilization, and other biomedical practices, were developed as first-tiered genetic engineering. These practices persist today and are alike with GMO development in that they require other than naturally occurring physical intervention to effect the desired result.

In 1992, the ‘Flavr Savr’ tomato was the first food crop approved for production by the USDA. In 1994, after years of research, Calgene, a California company, brought the first genetically-engineered crop to market. The company’s researchers were able to inhibit gene expression that produced protein that causes tomatoes to get mushy. Calgene developed and patented the technology to do this. Their objective, using this novel technology, was to create a tomato that would retain its flavor and texture for a longer period of time than possible with the existing traditionally-developed tomato varieties. It may be interesting to note that, at the time, there were over 600 named varieties of tomatoes. It is significant to note that the researchers were tweaking tomato genes, in tomatoes, to extend shelf life. This clearly would have had a positive economic impact in that, with less spoilage, there would be a higher percent of value recovered in selling a harvested crop. Good for the growers and handlers! As well, the improved shelf life of the tomato would have a positive impact on the consumers due to the improved flavor retention in this tomato. Good for the eaters! Arguably, a win-win situation. This was considered a great idea, worth the millions of dollars spent on development because most concentrations of population weren’t able to purchase ‘actually’ vine ripe tomatoes from their local farmers. People will pay high prices for good flavorful tomatoes; a big economic incentive. By creating the ‘Flavr Savr,’ the thought was that tomatoes could be shipped from distant fields and warmer climates and still arrive in perfect condition for display on a storeshelf. And, also, last longer on your counter before being used in preparing that amazing meal you are planning .

THREE CORPORATIONS CONTROL HALF OF THE MARKET

Calgene originally was very intent on developing a strong positive consumer response to the ‘Flavr Savr’ tomato because of the newness of the idea of the genetic engineering technology. They had very prominent package and fruit labeling and all of the marketing of this tomato was direct to the consumer. The ‘Flavr Savr’ development team was, in fact, operating as the grower for this project. In a very clear commitment to transparency and understanding the possible market resistance of consumers to GMO foods, Calgene even sought licensing from the FDA/USDA for the ‘Flavr Savr’ tomato.

The Monsanto Company, that had begun investing heavily in purchasing seed companies, bought shares in Calgene in mid-1995 to gain access to the patented gene manipulation technology and, subsequently, bought the rest of the stock in 1997. The Calgene scientists were self-described ‘gene jockeys, not farmers.’ They suffered some very embarrassing and costly losses as a result of their ignorance of commercial farming and marketing practices. Production of the ‘Flavr Savr’ was, subsequently, suspended and, ultimately, removed from the marketplace. Thus, ended the story of the ‘Flavr Savr’ tomato.

Also ended was any apparent willingness for full disclosure regarding GMO traits in food made available to the end-consumer. This is somewhat surprising because, at the time, there wasn’t widespread resistance to the idea of a genetically-engineered food being put in the marketplace.

It is important to understand that GMO products in the market, since the ‘Flavr Savr’ tomato was shelved, have different target customers from end-consumers. It is first necessary to market GMO products to the farmers in the form of seeds. If the farmers did not adopt the use of GMO seed, then there would be no GMO product to market as finished food or food ingredients.

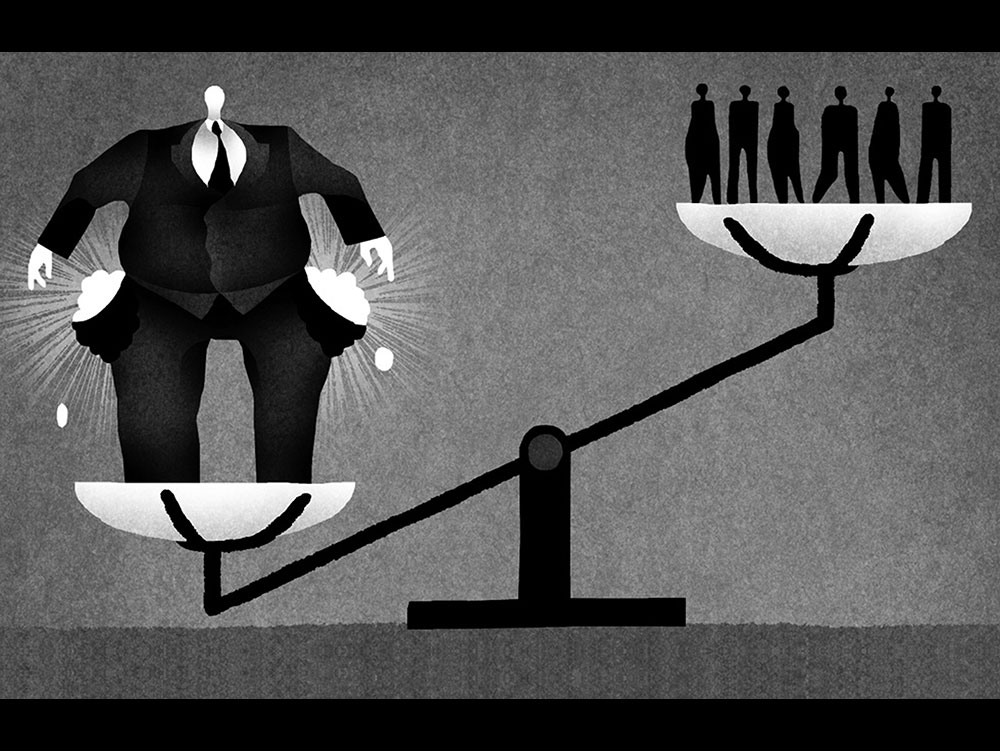

Reading the bold-print promotional material that GMO seed manufacturers have used to sell their seeds to growers, one would think that GMO seed is far superior to other non-GMO seed. However, this is simply not true. The early sales pitches have the ardor of the snake oil salesman especially since the touted gains have not materialized. Also, those strident claims have disappeared from marketing as control of the seed supply tightened. What has happened, though, is that control of the seed supply has become concentrated. Three corporations now control more than 50% of the world’s seed supply: Bayer, Syngenta, and Monsanto.

Monsanto, while not known to the seed industry before the mid-1980’s, is now the world‘s largest seed company. Its rise, accompanying the patenting of technologies, has facilitated the licensing to other seed companies and made producers dependent on the technology. The acquisition of biotech and traditional seed companies has expanded the company’s reach from cash crops into vegetable crops with holdings of over 26% of the global market. In 2010, some estimated 80% of the land planted with major field crops in the U.S. contained transgenic traits owned or licensed by Monsanto. Genetically modified crops are grown on 420 million acres by 17.3 million farmers around the world. More than 90% of them are small farmers in developing countries, according to the International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications, an organization that promotes the use of biotechnology. Vertical integration with firms like Cargill and Sysco has allowed essential control of corn and soybean distribution from ‘trait to plate.’

THE “BONUS” OF HERBICIDES AND PESTICIDES

The traits that have been engineered into the seed are predominately those that permit or encourage use of other products (chemical herbicides, pesticides) that are often produced by the same company selling the seed. There was, at first, a very loud and promising assertion from the seed companies that, by using the GM seed varieties, farmers could save money. This would be due to a reduced need for herbicides in the case of Bt-engineered genes and that they could more effectively use herbicide in a crop in the case of Glyphosate-tolerant crops. Bt presence and Glyphosate tolerance are the two predominant GE traits engineered into plants based upon acreage planted. Both of these scenarios (plant toxicity to pests and tolerance to herbicides), according to the sales pitch, would result in more of the crop being brought in at harvest. That was a very powerful inducement for producers to purchase the new seed. As one might expect, early adopters did see increases due to a higher harvest percentage and/or less competition from weeds. Originally, prices for this seed, while a bit higher than conventional seed costs, were comparatively reasonably priced. This cost was considered a small increase to gain access to more crop harvested as a result of using the GMO crop seed. And so the marvel of this new technology was marketed to growers with confident and forceful advertising.

The practical reality, as it has become evident over time, is that, precisely like every other example of overreliance on a chemical strategy to manage crop pests, these GMO tools are now failing. Nature in the inexorable fashion of life on our planet, has responded to GMO tactics in the same way nature has responded to conventional chemical products. The targeted pests are developing resistance, and/or new pests are emerging into the vacuum created by the absence of the targeted pest organism. This results in more chemical applications and new efforts to reintroduce chemicals that had been abandoned as too dangerous such as 24D.

THE APPEARANCE OF “SUPER PESTS”

At this point, let us pause for a moment and consider the observed cycle of rescue chemical strategy in “conventional’ agricultural production. The simple and dirty truth here is that, while chemical means and tactics have dramatic and very often immediate results, these results are short-lived in the context of evolutionary time. There is an entirely predictable cycle.

A ‘pest’ is targeted by a chemical that, when introduced into the environment, may have or generally has unintended consequences on the surrounding biosphere. (Note: In military terms, that is collateral damage. This term refers to an acceptable level of damage or loss when balanced against the net result of deploying the tactic.) The chemical is applied and, in general, the pest is killed to below the economic threshold impacting the crop. Other non-targetted pests often are killed thus increasing the biological vacuum that results from eliminating species from the biome.

Always, the application is not universal and some ‘treated’ pests survive. Those treated ‘pests’ that do survive may do so because of a wide range of variables, however, the net result is that some survive. Of those that survive, some have a natural resistance to the chemical used. These resistant populations cross breed and develop a population that is largely resistant. The largely resistant population grows during this recovery period after the initial die-offs and becomes a pest population with economic impact on the cultivated crop.

In cases where resistance does not develop, the removal of the pest from the biosphere causes a species vacuum. During the recovery period, during which target pests would develop resistance, other opportunistic species that are less affected or not affected by the chemical usage often move into the affected area. The long-term response of nature in the form of evolution is that resistant and opportunistic individuals (plant, insect, microbe etc.) develop in this void resulting in the emergence of a population that has an economic impact on the cultivated crop.

This imbalanced approach to agriculture, in part defined as overreliance upon chemical use, is the standard today. This cycle is fully understood and relied upon by the pesticide producers to stay in business. It has long been known that all pests develop resistance to a chemical over time if they aren’t eradicated outright. That demands that new chemical strategies must be developed to take the place of the preceding ones as they lose efficacy.

This fits ideally in an agricultural system where there is a reliance on large acreages of the same crop. Modern agriculture has been driven to take advantage of mechanical production efficiencies, labor being the most expensive business cost. The escalation of the practice of monoculture agriculture is clearly the result. Monoculture has played a key role in the chemical cycle. Some environmental scientists call this cycle the pesticide treadmill: as farmers and pesticide producers work harder to control pests, they create pests that are harder to control. The pesticide treadmill starts with the development of a new and powerful pesticide and hasn’t stopped yet.

THROWING AWAY CENTURIES OF KNOWLEDGE

With the Supreme Court’s decision to patent seeds comes a remarkable concentration of seed supply as mentioned above. This, in complete disregard to eons of tradition regarding seed saving. ‘The seed, the source of life, the embodiment of our biological and cultural diversity, the link between the past and the future of evolution, the common property of past, present and future generations of farming communities that have been seed breeders, is today being stolen from the farmers and being sold back to us as “propriety” seed, owned by corporations like Monsanto’ (Vandana Shiva).

Reading the fine print on a seed purchase contract, it is clearly stated that the grower is taking all of the risks that may result from using this seed. As well, the grower may not keep and replant any kept seed. The GMO seed can only be planted to harvest a crop for consumption. So, in buying this seed, every farmer purchasing the seed surrenders the privilege to plant a successive crop using their own saved seed. Effectively, giving up what has been considered a time-honored right millennium old, and stooping to agree to be sharecroppers for the seed corporations. Only now this is beginning to emerge as a discussion issue among farmers. Seeing other producers who saved seed being prosecuted by Monsanto for patent infringement has been a wake-up call for the farming population.

Due to the absolute lack of independent research and vehement resistance on the part of the biotech firms to external research, a large part of the controversy surrounding GMO material has simply to do with trust. Unfortunately, the behavior of the owners of the technology has not engendered trust. Recalling that Calgene initially made every effort to be transparent, it is remarkable that Monsanto and other GM technology patent holders are vigorously working to keep the results of research cloaked in near secrecy. Not only have they guarded their patents, they have rigorously attacked all negative press. Scientists and practitioners, completing independent research that published negative results, have been vilified and felt the brunt of aggressive counter attacks. Political pressure has also been applied in cases of negative results being reported to the effect that researchers have lost their positions. The shroud of secrecy, coupled with attacks on individuals, continues to raise more and more questions regarding the validity of the assertions promulgated by Monsanto regarding the safety of GMOs. As well, the efforts to orchestrate legislation in the U.S. to codify GMO protective language that would result in even less scrutiny of GMO development and use are highly provocative and disturbing. This, coupled with escalating pressure on other countries to accept the use of GMO material, really raises questions about the objectives of these large seed companies.

IMPROVING OR CONDEMNING LIVES?

This quote is taken from Monsanto’s website: “Producing more. Conserving more. Improving lives. That’s sustainable agriculture. And that’s what Monsanto is all about.”

There are a number of cognitive dissonances with Monsanto’s behavior and their statement. If they wanted to engineer seed to be more productive, that should be the focus of their research. They have engineered tolerance to their herbicide, Roundup®. They have engineered Bt into plants thus rendering each cell toxic to certain Lepidoptera caterpillars. If they were interested in conserving more, one might think that that might involve reducing chemical inputs when it is clear that they are up to increasing them for profitability. I’m not sure whose lives they are interested in improving. Certainly not the Indian farmers who have lost everything and taken their own lives.

Unfortunately, there is too little factual information regarding the effects of GMO products that is available, and provided by the technology developers. In farming terms, that all adds up to letting the fox guard the hen house.