There is a “religious renaissance” in China and the Government “is concerned”, sociologist Richard Madsen, a former Maryknoll missionary in Taiwan and one of the greatest scholars of Chinese culture, tells us. “Christianity, like Islam and Tibetan Buddhism, are especially troublesome because of their aspiration to universality, under a God whose law is superior to that of a temporal ruler, and to their international connections.”

Author of reference works, such as China’s Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil Society, Madsen notes that “there has been a continuing effort to repress Christianity,” which will account for about 10% of the population, and now even more so with a “plan of sinicization” imposed by president Xi Jinping, in the last congress of the Communist Party. It is a campaign to “nationalize” religions, requiring them to adapt to Chinese traditions.

Like Confucianism, the government hopes to “be able to supplant Christianity” – because it promotes loyalty to the leader and provides no moral basis for criticizing it. It is not surprising, Madsen said, that nearly 50 percent of the dissidents arrested for defending human rights and democracy are Christians. “This upsets Xi,” he says.

Within the framework of “sinicization,” many unregistered churches (a legal obligation) have been destroyed, crosses removed from their bell towers, images of Jesus replaced by photographs of Xi, faithful liable to heavy fines or prison sentences, as witnessed by the South China Morning Post newspaper. The regime justifies these actions with the need to ensure “social harmony.”

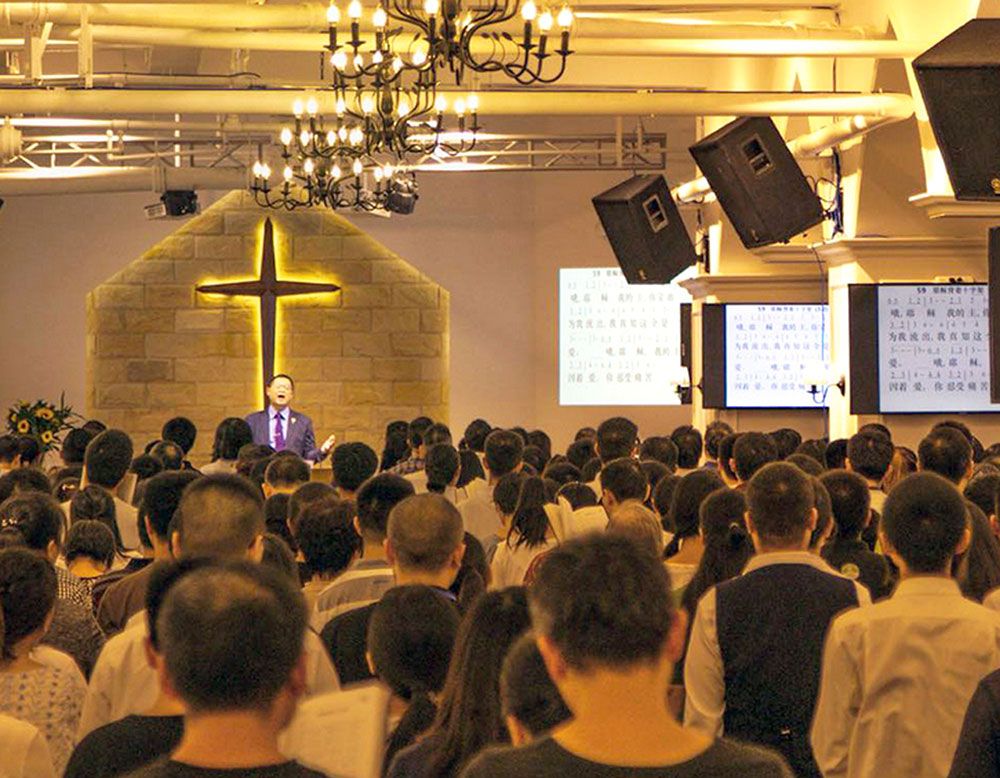

Protestant Dominance

It is very difficult to identify the exact number of Christians in China. The regime estimates that there are 25 million, 18 million of whom are Protestants and six million Catholics. In 2010, the Pew Research Center had 58 million Protestants and nine million Catholics. Other sources point to 100-130 million Protestants and 10-12 million Catholics.

According to the Center on Religion and Chinese Society of Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, USA, Christianity is the fastest growing religion in China “at an annual rate of more than 10%,” especially since four decades after “tolerance” of the reformist Deng Xiaoping replaced the era of persecution of Mao Zedong. Even if that pace slows to seven percent, “China could become the largest Christian country in the world by 2030, with 247 million believers” – mostly Protestants.

“Catholics have lost, in numbers, their predominance over Protestants, and this is one of their great challenges,” says historian David E. Mungello, author of several works, including The Catholic Invasion of China: Remaking Chinese Christianity. “In 1949, there were about 3.5 million Catholics and only half a million Protestants. By 2012, the two religions had grown, but Catholics had only three or four times more, while Protestants had increased exponentially.”

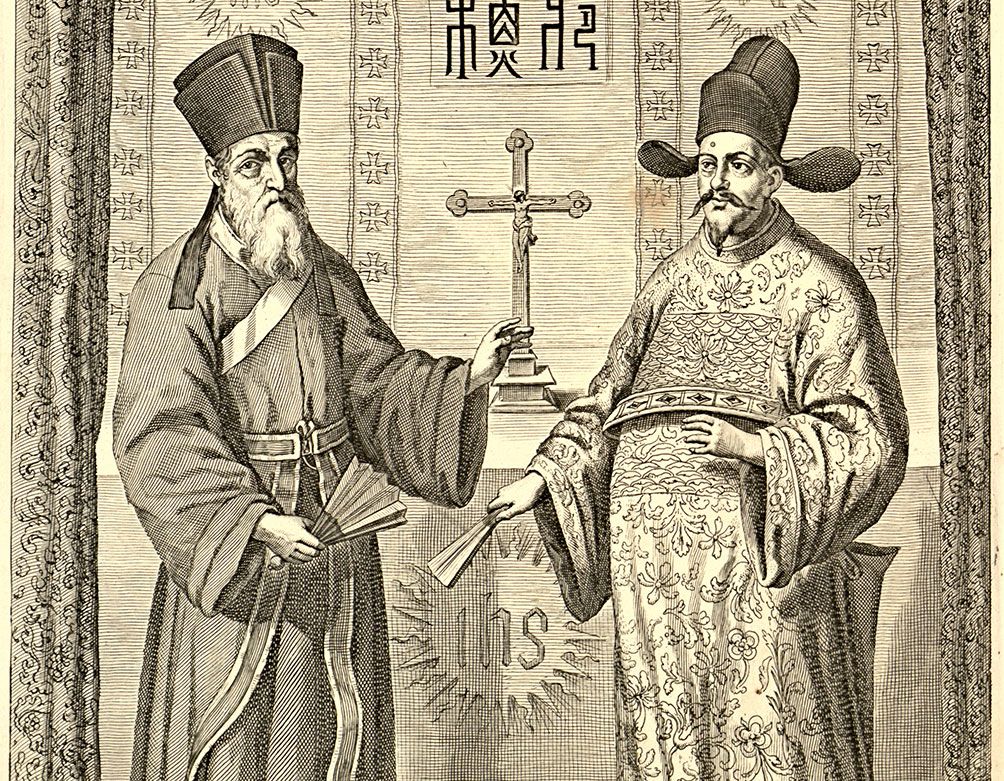

Why is it that Protestantism, which arrived in China only in the early nineteenth century when Robert Morrison of the London Missionary Society came to Macau in 1807, is supplanting the Catholicism with which Jesuit Matteo Ricci captivated the Emperor of the Qing Dynasty in the sixteenth century?

Explains the sinologist Mungello: “Catholicism is a universal church with a central authority in Rome, although it is more or less divided between a church with bishops approved by the government and an unofficial church with bishops obedient to the Pope. Protestantism has a decentralized authority and not a unified structure, a flexibility that has helped its rapid growth. Unofficial Protestant house-churches are difficult for the government to control. There is no defined hierarchy, with bishops or a pope with whom the regime can negotiate. This gave the Protestant churches freedom to develop distinct spiritualities.”

Communities in Crisis

The “sinicization” has targeted, in particular, Protestants, which Freedom House (independent watchdog organization dedicated to the expansion of freedom and democracy around the world) in 2017 considered as facing “a higher degree of persecution.” However, David Mungello is convinced that the aim of the regime is “to dominate rebellious elements in all religions, whether they are Catholics, Protestants or Uighur Muslims, subject to mass incarceration in camps in Xinjiang province in the northwest of China.”

The reduction in the number of those who refer to God as Tianzhu (Lord of Heaven) is not only due to the increase in the number of those who worship Him as Shangdi (Lord in the Highest). Other reasons explain that there are “more funerals than baptisms” among Catholics, as Richard Madsen, director of the Fudan-UC Center on Contemporary China at the University of California, San Diego, USA, observes.

The vast majority of Chinese Catholics live in rural, poor and isolated areas. In regions like Xi’an, for example, they constitute 90% of the population. In the last two years, a massive migration into the cities, driven by China’s transformation into an economic power, has profoundly shaken these communities, which Madsen defines as very conservative, distrustful of central government, modernity and secularism. The low birth rate caused by the one-child policy, which was in force from the late 1970s until 2015, greatly affected Catholic families, which transmitted the faith from parents to their children. The average age, Madsen says, is now 75 years, which makes more acute the crisis of vocations.

“Catholics would like to evangelize, attract new converts, but repression by the government and the division of the church into an ‘official’ [Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association] faction and a ‘clandestine’ faction makes this mission difficult,” says Madsen.

Accommodation and Martyrdom

Repression continues to be practiced because Catholicism “is still seen by many Chinese government leaders as a foreign and invasive religion,” says David E. Mungello. “When Catholic missionaries arrived in China in 1579, they were forced to negotiate from a position of weakness with a strong imperial government in Beijing. Today, once again, China and its central government are strong. Xi Jinping is an authoritarian leader who imposes restrictions on religions. It is not a new trend, but a reaffirmation of traditional Chinese authoritarianism.”

The Catholic response to repression, especially since 1600, Mungello recalls, has followed two standards. “The first, developed by the Jesuits, privileged accommodation, that is, willingness to respond to official demands in the hope of improving one’s ability to practice the faith. The other pattern emphasized martyrdom, believing that the blood of martyrs would be the seed for new Christians and conversions would allow Catholics to grow in order to counter oppression.”

“These two standards of accommodation and martyrdom still prevail today,” says the American historian. “Each pattern has its proponents, but history does not provide clear evidence that one is more effective than the other, so many Catholics try to imitate Christ by combining the two standards of action, though both tend to diverge.”

Pros and Cons

These patterns may help to contextualize the reactions to Pope Francis’s efforts to bring the Vatican and China back together from relations cut off since the 1950s. “The attempt to dialogue has further divided Chinese Catholics, many of whom consider the ‘clandestine church’ a refuge which protects them from wolves in the government,” admits Mungello.

After ten years of preparation, an agreement that many do not hesitate to consider historic, was announced on September 22, recognizing the legitimacy of the Vatican in appointing future bishops of the Chinese Church. On the 26th, in response to critics, Pope Francis clarified: “This is a dialogue, but it will be the Pope who will name [the bishops]. Let this be very clear. (…) I think of the resistance of the Catholics who suffered. And yes, they will suffer. There is always suffering in a deal, but they have a lot of faith.”

One of the main critics has been Joseph Zen, a former cardinal from Hong Kong, born in a Catholic family in Shanghai, who accused the Pope of “betraying” the faithful. Zen’s opposition, which was reprimanded by the Vatican, deserves the sympathy of Anthony E. Clark, a professor of Chinese History at Whitworth University in Spokane, Washington, and author of China’s Saints: Catholic Martyrdom during the Qing, 1644-1911. “I am very disappointed,” Clark lamented, noting that Francis, in signing an agreement with Beijing, “is following a very different path” from that of his predecessors, in particular John Paul II, who considered the communist regimes a threat to the world. “It seems that the Holy See is acting ingenuously and accepting a dangerous compromise.”

Newly returned from China, Clark says that most of the Catholics he met, while anxious for a visit from the Pope, “are confused by Rome’s apparent alignment with a government that has been inconsistent in the treatment of Christians” and that “openly claims to intend to eliminate religion.”

Clark suspects the “contradictory messages” sent by Chinese leaders, but sociologist Richard Madsen looks on the Vatican’s efforts as “a risk worth pursuing” to “revive evangelization” even if the Communist Party “expects an opposite result.” For Madsen, the agreement announced in September “was the first step in a complicated negotiation on relations between China and the Vatican,” in a specific area “where the interests of both parties converge.”

“Contrary to the failed negotiations in the past, when a broad range of issues – including the diplomatic recognition of the People’s Republic of China and not Taiwan – were tried to be resolved at the same time, this time the negotiators focused on a smaller package – the appointment of bishops who serve the Church officially registered.”

Resist and Survive

Until now, although “more than 95 percent of the bishops” were already approved by the Vatican and the Chinese government, it was “an informal and complicated process,” Madsen said, adding: “A representative of the Vatican, in a featureless office in Hong Kong, collected information on possible candidates for bishops and sent it to the Vatican. There were then informal discussions with local and national officials to reach a consensus on a candidate acceptable to both parties. There was an ad hoc nature here: the information gathered by the Vatican representative – who could not travel to Mainland China – was necessarily imperfect.”

The agreement announced in September, which “is in tune with Canon Law, as the Church always claimed,” also seems to address another issue, related to the status of eight bishops ordained without authorization from the Vatican and, consequently, excommunicated.

“China wants them to be recognized and the Vatican has accepted ‘to forgive them’”, Madsen reports. “I suspect that some of them may be ‘convinced’ to resign. Currently, 100% of official bishops are already approved by the Vatican.”

What remains to be resolved, says the American sociologist, is the status of the bishops of the ‘clandestine church’, accepted by the Vatican but not by the regime. “I thought this would be over, but no! In addition, the agreement is also ‘provisional’, that is, it may be revoked if one of the parties does not like the course followed.”

For the historian of Sino-Catholic relations David E. Mungello, the agreement “is more a promise than a long-term solution, to serve, above all, the interests of the hierarchies” of the Vatican and China. “It is a temporary victory of the forces of accommodation to which those who draw inspiration from the memory of the holy martyrs of China will resist.”

For them, the commitment “is not worth the sacrifice of Catholics who were arrested or persecuted for their faith.” However, he concludes, “if in a short-term, Xi Jinping is a major threat to the Catholic Church, in the long run, a history of more than four centuries marked by so many acts of devotion and thousands of martyrs has probably left the Catholic Church in China capable of resisting everything.”