At six years of age, I aspired to be a cartoonist and drew many airplanes in flight. That was my first ambition, so curious to my first grade teacher that she wrote on my report card for Mom and Dad to see: “Bobby is living in a world of airplanes.” One year later that ambition morphed; I then wished to pilot the airplanes. The following year’s ambition changed again, as happened every year thereafter, when I wished to become a military officer, a cowboy, a pro athlete, an archaeologist, and so on until the first year of college when I realized that what I really wanted to do was something honorable and admirable with my life. Somehow, religious life had never occurred to me during my first nineteen years!

Then, suddenly, as I walked to my off-campus rented room at the close of the students retreat for 1956 at Seattle University, God stopped me in my tracks near the corner of Summit and Seneca Streets. Become a priest; become a missionary, was the crystal-clear inspiration. “Trust Me. My love is enough for your happiness. Give Me your everything.” That unmistakable message grabbed me. Why had I not ever thought of it? I asked myself, “is there anything now that prevents me from saying yes,” i.e. let it be. It was God offering me a life of happiness. “Trust Me,” for this is not a joke or fake attraction. “My love is enough for your happiness. I Myself will take care of your loving relationships. Give Me your everything. I would not attract you to this way of life if I were not going to be with you always.” Those thoughts were God-given to me. During God’s stunning approach to me, I felt completely free to refuse the invitation. I was absolutely sure God would not punish me for turning down the offer. I also knew that I would be a first-class fool to say no to God. After those moments alone with God on the sidewalk, I begged the Inspirer not to depart. “O God, please don’t let me mess this up. Strengthen and prolong the desire You have put into my heart. Help me to do Your will.”

My First Bicycle

I am a Midwesterner, born in Des Moines, Iowa and raised in Goshen, Indiana, a town with a population of 10,000–13,000, more than 50 churches, and lots of good people. The majority were Protestants, the largest group of them Mennonites, persons with an appreciation for foreign missions. Our Catholic parish was small.

An incident from childhood comes to mind. We two elementary school boys were playing in our backyard. During a conversation, he informed me: “Catholics cannot be saved. My mother told me so.” I offered no rebuttal. He may not even have known he was playing with a Catholic. What impressed me at that moment, and thereafter, was how silly the statement was. I felt that well-behaved persons are good. We accept them. To be damned for belonging to any religion is ridiculous, I thought. Besides, I liked being a Catholic. How could it be bad?

At eight years of age, I bought my first bicycle, a Columbia model, and used it for delivering newspapers—my first paying job. Probably, no skill I have learned since then is more useful to my missionary apostolate.

Another formative experience of my five years as a newspaper carrier was to receive the satisfaction that comes from doing a job on time and well. I seldom missed delivering papers to a customer, and even when I did miss, the customer viewed me benignly. Fault finders were fewer in those days.

High school years found me in a class of 130 students; only three of us were Catholics. I still remember my fellow high school students better than any subsequent group. My Protestant schoolmates and neighbors thought well of missionary work. Missionaries were much respected. Their senders and supporters in our small town were invited to share their experiences of other peoples and cultures.

Mining Gold

After high school, I enrolled at Marquette University, the first Catholic educational institution I had ever attended. By the year’s end, I was financially broke and in need of a good summer job. A chance to go to Alaska came my way. In Alaska, I mined gold, assisted a surveyor, and finally drove a truck (in which I nearly lost my life due to failed brakes). That near-death experience caused me to pause and think deeply, but the thoughts were soon forgotten. They only returned to remind me of God’s mercy on October 31, 1956, after the students retreat at the beginning of my second year of college.

Seven years of seminary followed. At ordination in 1964, I had an assignment to the Philippines. During 11 years I lived in remote areas, travelling often by motorcycle where there were roads or on foot in the hills, to be with farmers in their barrios and at their fiestas. It was a busy and satisfying life of service to people who looked to God for consolation and support. The poor and I gave encouragement to one another.

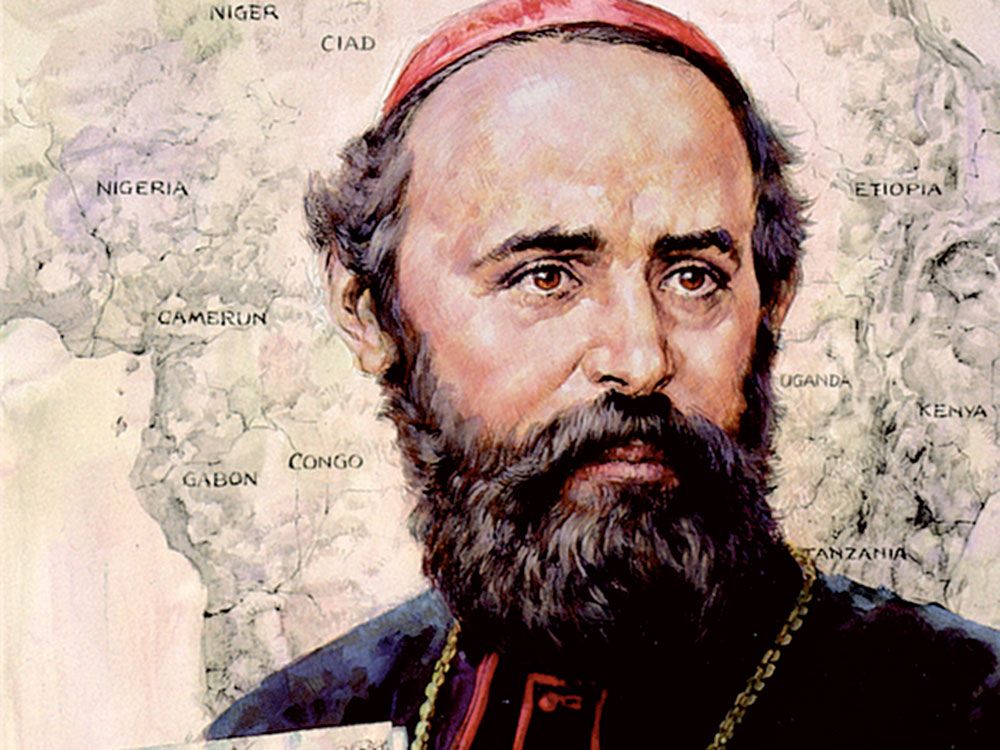

An invitation for priests to work in Bangladesh was given to the Maryknoll Society in 1975. There were five of us who volunteered, arriving on December 2, 1975. The Holy Cross Fathers and Brothers had been in Bangladesh since 1852. They helped us make a start in Bengal 123 years later. After our language school studies, we requested our sponsor, the Archbishop of Dhaka, to give us permission to live among the Muslims. Although it was not the work he had planned for us, i.e., parish apostolates, he agreed to our request because we had “decided in prayer” to make our request.

Bob Brother

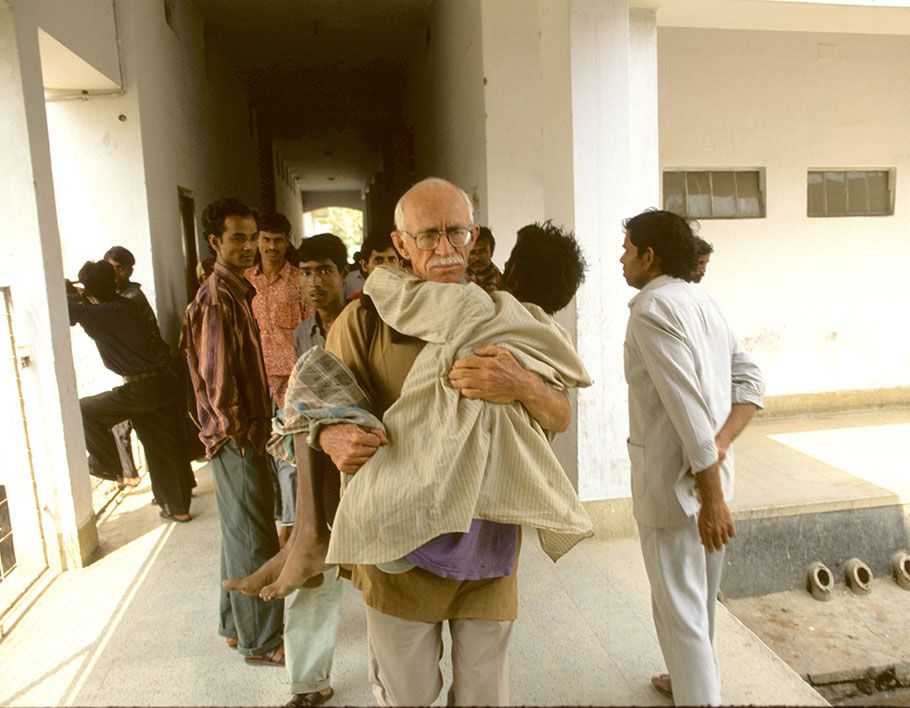

At the beginning of our eighth year in Bangladesh, the community of five was reduced to two. Fr Douglas Venne and I decided to leave Tangail, the place where we had lived for the previous eight years, to go to places we felt the need to be as witnesses of our brotherhood with Muslims and Hindus. Doug chose to be a village-based farmer; I chose to be a seeker-helper of the disabled. Thus began my programme of spending three years in a town and then transferring to another town and district. Curious Bengalis wanted to know why I had come to live among them. “What do you do?” they needed to know. An educated young friend offered cogent advice to me while I searched for the best service I could offer. He informed me that my desire to work freely for the disabled poor and to bring them to better health at my expense, was unbelievable. “Frankly speaking”, he told me, “we think altruism is a hoax.” No Bengali Muslim trusts a pretending servant of the poor. “Everybody wants a reward.” His advice confirmed me in the determination to do works of mercy freely and gladly—as I believed Jesus, my Model in life, did. Another young friend reminded me of the very purpose I had set for myself: “It is not enough to merely be present among us. You must be doing something for the poor!”

I have enjoyed being a Christian witness in twelve towns and districts after having left Tangail, the only town we lived in as a community. To be a Christian among Muslims is my purpose. To illustrate our feelings of Christian brotherhood with all people has been my effort. Searching for (on bicycle) and finding persons in great need of medical attention or surgery has helped folks understand my name: Bob Bhai (Bob Brother).

A Simple Lifestyle

I go around villages and bazaars, between one and thirty kilometers from where I dwell, searching for persons in need of a brother’s help. I wish for nothing from them but the opportunity to be useful to them. As the years have passed, I have limited the service I offer to young persons and children having these three characteristics: they are young—up to age fifteen years; they are poor—and cannot imagine seeking professional help; and they have serious conditions—medical, surgical, or therapeutic. I hope to make the disabled poor more able. I am pleased to be recognized as their brother.

Every town I go to live and serve in is a new experience. The early days found me prone to anxiety, especially on the first day. Would I find a place to stay for a few days while I searched for a more permanent place? Refusals to rent to me, brush-offs, and exorbitant rental demands: I met with them all. God inspired me to trust during those days. “Trust Me!” urged me to hang on, to keep seeking, to refuse discouragement. God has always arranged living conditions for me which demonstrates how important it is that a missionary among Muslims and Hindus has a simple lifestyle. It must be a simple lifestyle.

Simplicity refers also to cooking for myself on a single burner kerosene stove. It feels good to fix my own food. Before leaving my shelter every morning to ride my bicycle to villages, I have a boiled egg and a large banana. Then, on the road, perhaps an hour later, I stop for parata dipped in lentils. At noonday, I eat a snack named shingara and drink lots of water to replenish the fluids I lost through biking. Then, in the afternoon, at 4, I enjoy my daily cooked meal: rice and lentils mixed with veggies such as potatoes, string beans, okra, small squash, seasoned with a five takas packet of spices. All are cooked together in one pot for 12 minutes and I do not tire of it. Neither meat nor fish are necessary. Vegetable kichuri satisfies. Another banana and a biscuit top off the meal. “You eat that, daily?” sceptics ask. I reply: “If you are hungry, you eat.”

I Came To Serve

During the first year of the three I intended to spend among them, many, even most, suspect I came for the purpose of converting them—but I did not come to do that: I came to serve. I wish to change nothing in you except that which you also wish changed, i.e., poor health to become better health. Why do it? Because Jesus went around doing good and healing, and because the sign atop a hospital in Mirzapur of Tangail District proclaims SERVICE IS THE BEST RELIGION and because the Prophet said those who serve the poor thereby serve Allah.

Occasionally, I am approached by a tester who declares, “I will become a Christian…what will I receive?” “Suffering,” I reply. Cunning individuals and opportunists go away disappointed.

By the second year among them, trust is built and increases. Most people see and understand I came to serve, like a brother to all peoples. More people accept my help. Doctors and nurses cooperate nicely for they see my help is freely given and not for profit.

By the third year, there is widespread affection for the missionary. They detect that I receive happiness and peace by the service I offer the poor. They see that sign of Jesus and appreciate it. Having made that sign, I can then move on, for Jesus normally moved on as He explained that “to other towns also I must go.”

You Are An Angel

It needs to be remembered that the acceptance of a Christian missionary by the Muslim faithful is as outstanding an accomplishment for those who receive Christian witness as it is for those who give Christian witness. The history of what is now Bangladesh is colonial, that is, they have the history of the local population being exploited by foreigners. Even farther back in history, the Crusades give reason for hostility towards Christians. Thus, to accept the Christian’s witness of service without any expectation of a reward is difficult for many Muslims to believe. The openness of Bangladesh Muslims and Hindus to accept and appreciate the Christian servant is, in itself, proof of a converted heart. Suspicion is relegated along with hatred for the distant past, opening the door to brotherhood.

Occasionally, I cross paths, by accident, with persons I had known in other towns and times. Recently in Dhaka, on a bus, the young man beside me—whom I did not recognize—reminded me of the services I had offered to the poor and disabled in his town and district. Finally, he summarized his feelings for his once-upon-a-time neighbor: “People there say you are a feresta” (in Arabic, an angel). I know quite well that I am no angel, so I replied to him: “You mean people say I am a feringi” (in Arabic, a foreigner). “No!” he protested gravely. “You are an angel because you do what angels do: you come as a stranger and bring benefits to persons in need.”

Thus, I am no mere foreigner. I am their brother, indeed.

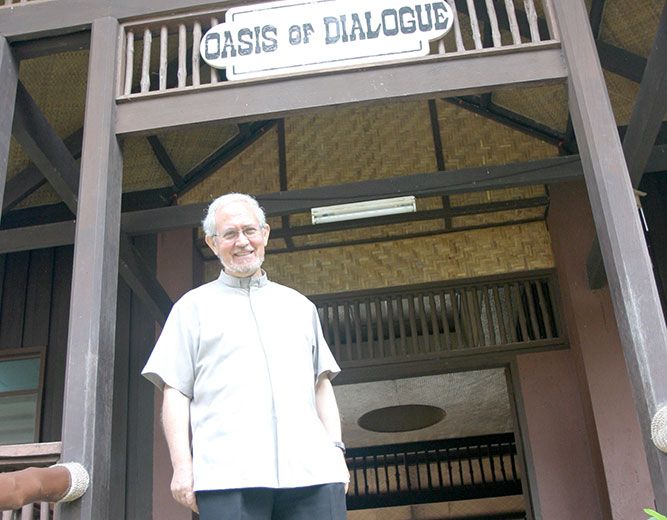

Dens Of Dialogue

Church persons ask me, “What is the result of your lifestyle and service among Muslims?” My answer will have no exactness nor am I expecting positive feedback in order to continue this apostolate. All apostolates depend on God and I feel that what I am doing is God’s will for me. I reckon that God has prepared me by my early life and environment for just such an apostolate. The happiness and peace I experience is surely God-given and is a sign I should continue on this path for as long as stamina—physical, mental and spiritual—remain.

Am I practicing a form of dialogue that the Church approves? Surely so, because each and every Christian is readied by God, guided by the Spirit, led by our Model in life, Jesus, to fulfill mission in multiple ways. My way happens to be a way of dialogue with persons of other faiths. Seminary training and spiritual education have their parts to play in our lives of dialogue. Basically, it is our willingness to relate to persons of other religions, to converse with them, and to live exemplary lives among them that unify us. We pray for the courage to place ourselves wherever dialogue and trust can blossom and flourish. The ubiquitous tea stalls of the sub-continent, are suggested to us as dens of dialogue.