For many years, forced migration or displacement has taken one of two directions in Central and North America. The best-known direction is south to north. It started with the Mexican flow, which was later joined by those from Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Their common destination is the United States, “the American dream.” On the other hand, from north to south, we see mainly Nicaraguans heading for Costa Rica and Panama.

From here on, we will focus on the south-to-north flow in the two directions described above. It should first be noted that recently, the flow of migrants wishing to enter the United States has greatly increased due to the “call effect” brought about by the change of president.

Joe Biden’s electoral victory increased the expectations of the forced migrant flow since, in the electoral campaign, he explicitly promised to revoke the anti-migration policy imposed by Donald Trump.

ANTI-IMMIGRANT POLICY

More than two years have passed since Joe Biden became president. The aggressive tone has softened, and the construction of the physical wall has been cut back. Still, Biden has failed to adopt measures capable of reversing the anti-immigrant orientation of the US migration policy. The message to the Central American population remains: “Don’t come, we won’t let you in.”

The pandemic-related health crisis, adding to the systemic health crisis, has increased and accelerated both the need to migrate and the risks and vulnerability of the population forced to migrate. At the same time, it offered Trump the pretext to enact the law known as “Title 42,” designed to close the land border and simplify immediate deportations. Biden has kept it in place, contrary to expectations.

If the situation is looking more and more like a dead end, it is also due to the behavior of the Mexican government, which, complying with Washington’s dictates, welcomes the thousands of people deported through “Title 42” and those sent back under the “Remain in Mexico” program.

But Mexico has accepted these impositions without developing a clear and effective plan for essential services and job opportunities and without offering any guarantee of security to those vulnerable people crowded on its northern border. In addition, Mexico has also hardened its migration policy, increasing deportations, reducing the opportunities for regularization, and using the protracted nature of the asylum application process as a deterrent and containment measure that blocks the passage to the United States at the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

The governments of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras were left with no choice but to adapt in turn and become safe third countries. It seems that these three governments, as well as that of Nicaragua, are not taking measures to reduce emigration from their countries because this generates remittances that are the main monetary source of income for their countries, as well as a fundamental contribution to the sustenance of the families who receive them.

THE EFFECTS OF THE BLOCKADE

The first effect of the blockade is the creation of increasingly explosive situations at the borders, especially at the two entrance points in Mexico, the one in northern Guatemala and the one in southern Panama.

With emphasis on security, human rights violations against the forced migrant population have increased. With the policy of refusal of entry, an increasing number of people live in crowded and inhuman conditions, blocked and frustrated in areas with a high incidence of violence and without any prospect of finding a well-paid job that would solve the needs that pushed them to emigrate.

A second effect can be seen in the multiplication of the caravans of migrants that leave not only from Central America, but also from Mexican containment towns, such as Tapachula, near the border with Guatemala. The very fact that these caravans continue to form, despite being violently attacked to disperse them, expresses the desperation in which the people in the countries of origin find themselves.

A third effect of the blockade is the significant increase in the number of migrants arrested and deported by the US and Mexican governments. Fourth, there has been an exponential increase in the number of asylum applications made to the Mexican government, with as many as 108,195 requests from foreign nationals from January to October 2021.

Fifth, the dangers of forced migrants have grown. The path migrants must follow today is longer, more dangerous, more expensive and presents greater obstacles with less likelihood of reaching their goal, especially in the case of the most vulnerable. As a result, there is an increase in the number of people murdered or victims of extortion, torture, kidnapping, or forced disappearances. There are also more wounded, maimed, and accidental deaths; more people are drowning or dying of dehydration in the attempt to ford rapidly flowing rivers, to cross the desert or the Darién jungle.

Sixth, organized crime is dramatically increasing its illicit profits. It is now the criminals who control the main migration routes, the channels of human trafficking. They receive more and more requests from people wishing to move to Mexican territory and/or to cross the US border because relying on them is more likely to succeed, although it is far from risk-free. As conditions have become more difficult, the rates of engaging the services of these criminals have risen from $8,000 to $20,000, and even $30,000, depending on the distance to be covered, the means of transportation used, and the route taken.

PROPOSED SOLUTIONS

The main solution proposed to overcome this impasse for the US and Mexican governments has resulted in the elaboration of regional development plans for Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Certainly, it is necessary to promote regional development, but this does not take away from the necessity and urgency of finding an immediate solution for the thousands of people who remain stranded.

However, the plans proposed so far risk being little more than illusory. The American plan calls for millions of dollars to be invested in the same initiatives implemented in the past without significantly reducing the causes and without bringing benefits to the people they targeted. On the contrary, they have increased opportunities for corruption and diversion of funds to pay high salaries to those who promoted or managed them. As for the Mexican initiative, it is limited to giving scholarships and grants to plant trees.

Consequently, if incoming flows toward the United States are to be reduced, it is no longer sufficient to mitigate the causes in only three countries from which they originate. For a regional development program to be effective, it probably needs to involve all the countries in the region. Under current conditions, any local plan, in isolation, is unlikely to be economically sustainable.

SIGNS OF HOPE

We want to conclude our description of the Central and North American migration context by highlighting the many signs of hope that exist in the region. It is clear that the growing flow of migration, despite such adverse conditions, continues because the people who take part in it receive significant support from an important sector of civil society.

First, there is support from family, friends, and compatriots already living in the United States. It is they, in general, who provide financial support for the relocation of the forced migrant population, paying the traffickers, bearing most of the costs of the journey, paying ransom for the kidnapped, and/or taking in those who manage to arrive at their destination, at least until they have found work.

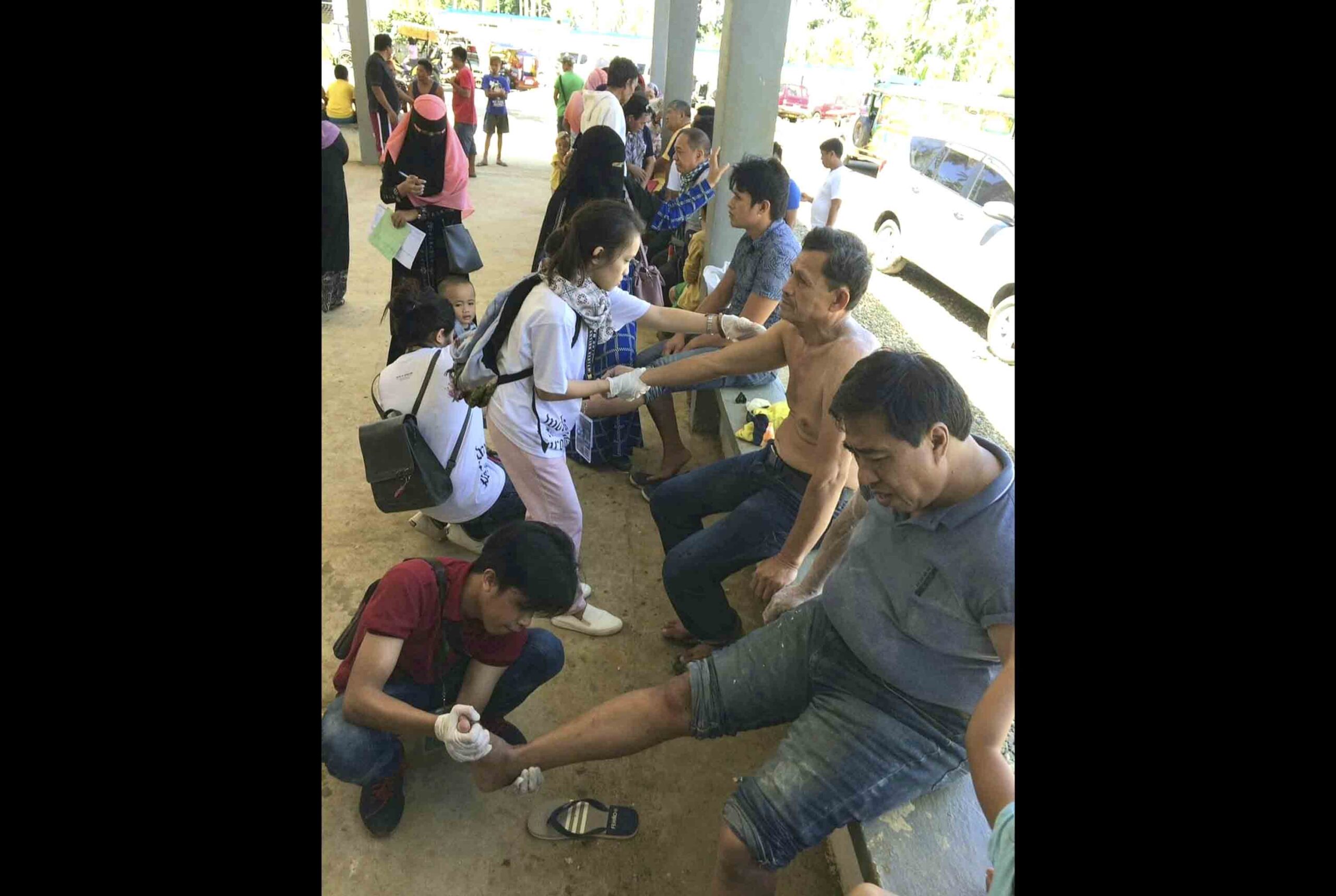

More than 100 shelters administered by churches or philanthropic associations scattered along the various migration routes offer migrants free food, hospitality, clothing, medicine, spiritual and psychological support, and legal advice.

The many non-governmental institutions that advocate for migrants record the violations that migrants suffer along the way and in their countries of arrival. They also highlight the benefits and cultural and economic contributions that migrant populations bring to their host countries.

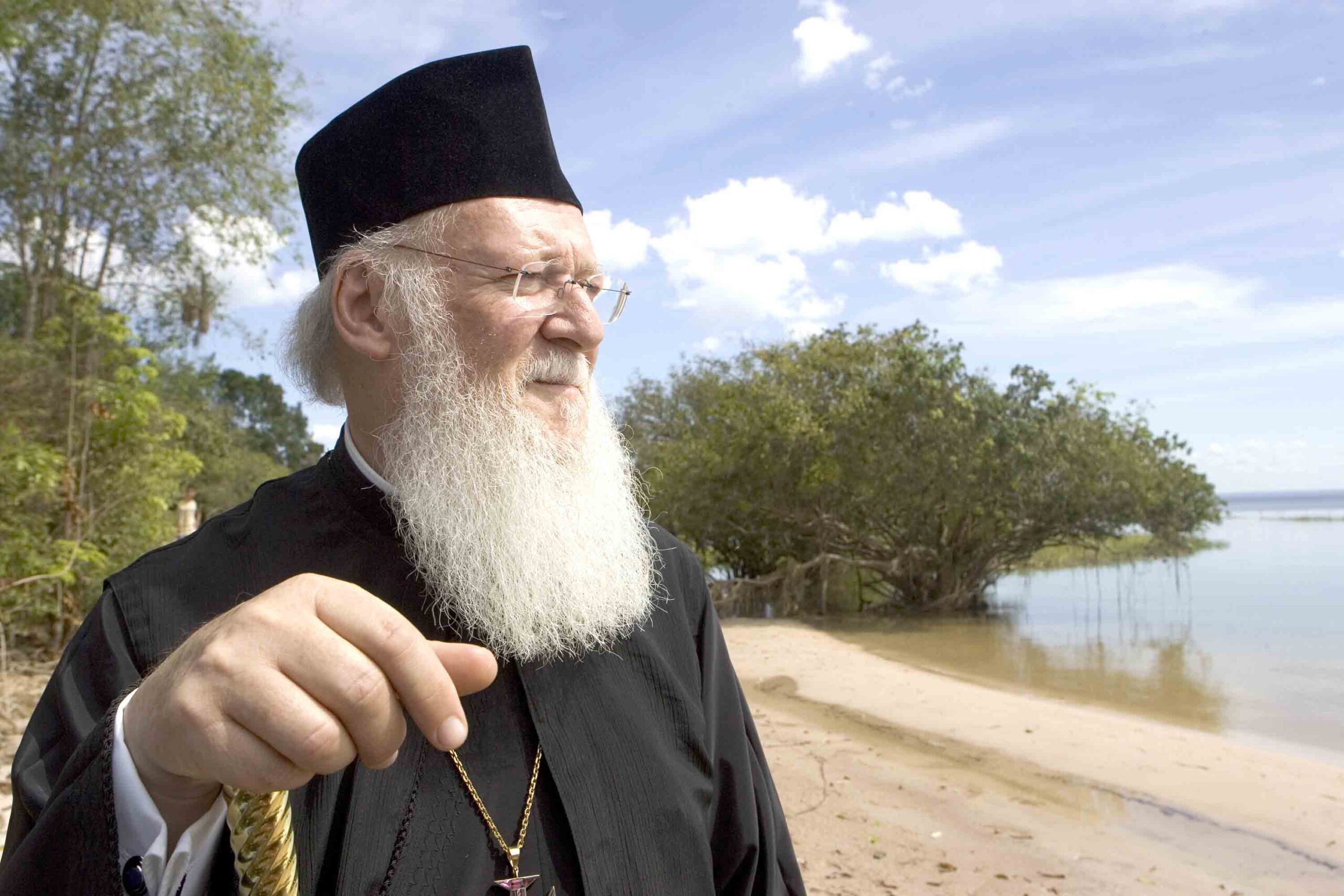

Pope Francis’ testimony on behalf of migrants, refugees, and internally displaced persons has undoubtedly been decisive in multiplying, fertilizing, and connecting these seeds of hope. By setting an example and speaking to us of “universal fraternity,” he proposes the main remedy to one of the structural causes that most influence the closing of borders and the emphasis on national sovereignty.

The hope he holds in addressing these and similar exhortations to us is expressed very well in this passage from the encyclical Fratelli Tutti (FT): “Let us take a step forward toward a new style of life and rediscover once and for all that we need one another, and that in this way our human family can experience a rebirth, with all its faces, all its hands and all its voices, beyond the walls that we have erected” (FT n. 35). Published in Civiltà Cattolica