It is a phenomenon that exploded in the 1970s. Today, thanks also to the media campaigns, it is overbearingly topical: the Philippines, an archipelago of more than 7,500 islands populated by different ethno-linguistic groups, is a platform for massive migration, offering workers, both skilled and unskilled, to the most developed regions of the world. The phenomenon is on a perpetual upward trend and has inevitably been called into question in human rights campaigns, highlighting the exploitative conditions of workers.

A well-rounded analysis of the phenomenon cannot but record that over the past 50 years, a ‘migration culture’ has gradually taken hold in the Philippines, with more and more Filipinos eager to work abroad despite the risks and vulnerabilities they may face. As early as 2002, a nationwide survey conducted by the Pulse Asia Institute found that one in five Filipinos expressed a desire to migrate. In more recent surveys by the same institute, that number increases to 30% and even 50% of respondents.

The characteristics of a mentality that has become a ‘typical trait’ of the national culture are proposed with narrative acumen by the film La Visa Loca, a 2005 Filipino comedy-drama directed by Mark Meily, recounting the paradoxical events of a Manila taxi driver who dreams of going to the United States. The film perfectly portrays a process on which, over the years, a myriad of clichés has thickened: the feverish search for a visa to the US, the airline ticket perceived as a finish line to the ‘promised land,’ the dream of a ‘nabob life’ in Uncle Sam’s country. Other ‘promised lands’ are the rich nations in the Middle East, Asia, Europe, and Oceania. The reality is, as ever, more complex and multifaceted.

NEW HEROES

The diaspora of Filipino workers worldwide now totals almost 10 million people, about 10% of the total population (100 million Filipino citizens). Migrants working abroad send massive remittances ($33.5 billion in 2023) that contribute to the economy and support thousands of families. Yet in the popular and internationally propagated view, the Filipino migrant is a ‘suffering martyr,’ enduring at the cost of unspeakable sacrifices the challenges of living in a foreign environment, vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, experiencing loneliness and depression due to separation from family.

Many recall the definition of Philippine President Corazon Aquino, who in 1988 called overseas Filipino workers (Overseas Filipino Workers) bagong bayani (“new heroes”), emphasizing their sacrifice for the benefit of an entire national community.

It should be noted that-building on a process that started as early as the early 1900s due to the colonial relationship between the US and the Philippines-the official push to emigrate has been curated, promoted and sponsored by the Manila government since the 1960s (with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 and, later with the Labor Code of 1974 ) and has found political continuity with governments of all colors and backgrounds, from general-dictator Ferdinand Marcos to the present day, sometimes stigmatized for neoliberal policies that encourage the exodus of migrants.

There are more than 1,000 official, government-licensed (not counting unlicensed) recruitment agencies nationwide that connect workers with foreign employers. In the Manila government, the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration provides support and assistance to migrants and their families, and the Commission on Filipinos Overseas offers programs and services to permanent migrants.

The reasons for the mighty institutional commitment are well understood. Besides alleviating unemployment, Filipinos who choose to work abroad send home remittances that have become an important pillar of the national economy. In 2004, according to the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, remittances sent through formal channels amounted to USD 8.5 billion. In 2005, remittances exceeded USD 10 billion annually and, in an ever-increasing trend, now account for 9% of the national Gross Domestic Product.

The representations of heroism, then present in cinema and culture, continue to perpetuate a stereotype. A different point of view appears from the writings of the migrants themselves, as can be seen in the text “The Filipino Migration Experience” (NY, Cornell University Press, 2021) by Filipino historian Mina Roces (professor of history at the University of Michigan, USA), which offers a new and original perspective to understand the migrant experience.

ACTIVE IN THE HOST SOCIETY

They are now consumers and investors, entrepreneurs, activists, scholars and philanthropists. And, as active members of the societies to which they choose to move, they are also valuable witnesses to their faith in Christ. After only a few years in their destination countries, they can also change the welfarist mentality of their family of origin, breaking cultural taboos and criticizing it for its relentless and exclusive demand for remittances.

Filipino migrants, notes Roces’ text, in Western societies, are often able to free themselves from menial jobs, integrate and acquire a new middle-class status, immersing themselves in the business scene and even generating profits. “Migrants,” notes the scholar, “are also able to change the host countries in which they live and work,” on a social, cultural, and religious level.

In Australia, Filipino trade unionists succeeded in the 1990s in changing legislation relating to immigration and domestic violence, demonstrating that they could influence national policy despite being a minority ethnic group or considered marginal.

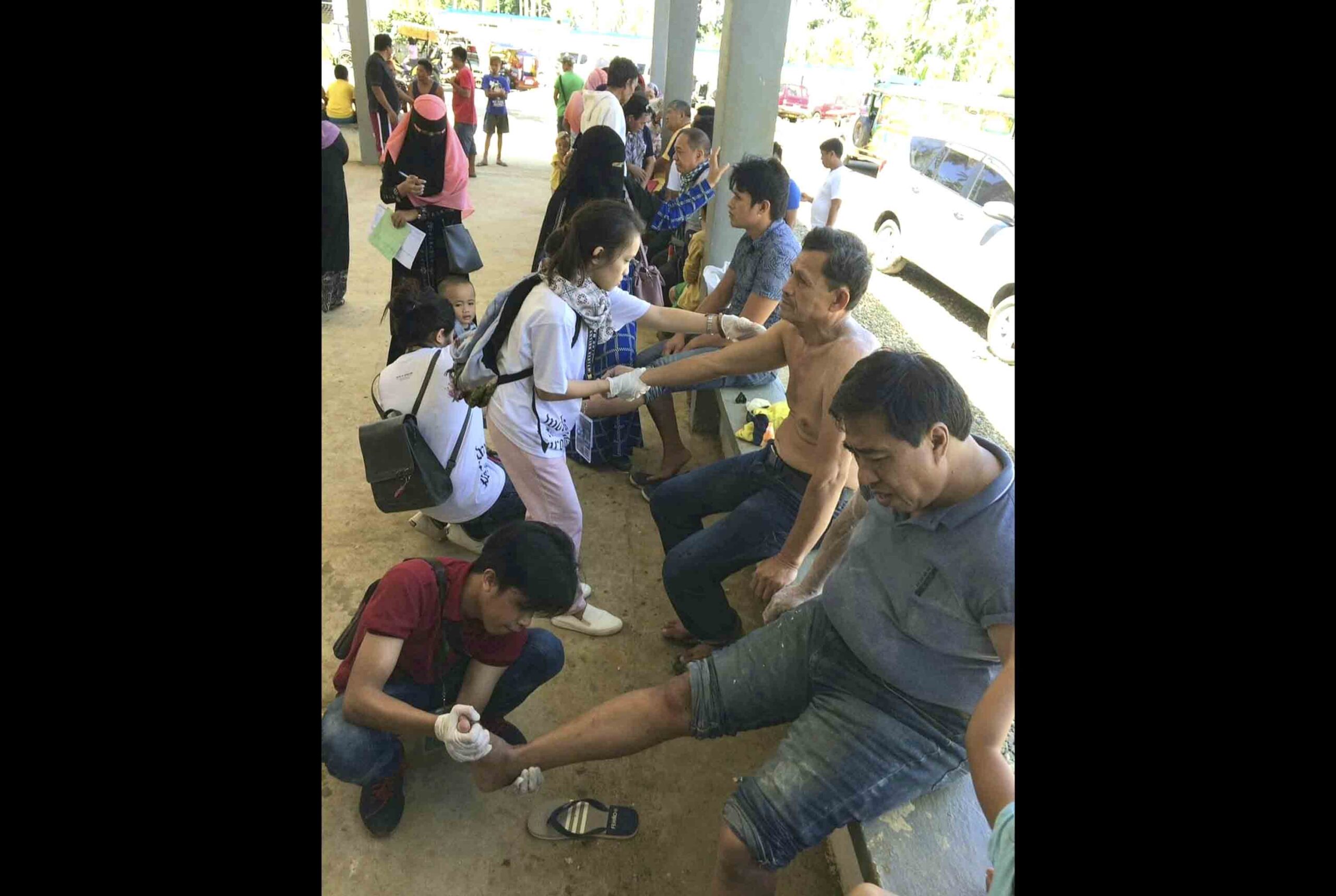

The text further reports that Filipino residents in the United States have participated in many philanthropic projects, such as the San Francisco-based Philippine International Aid- The Children’s Fund. With a budget of over USD 90,000 per year for 30 years (1986 to 2013), the Fund provided education and material support to disadvantaged children in the Philippines, benefiting some 300,000 families. Still in the field of healthcare, the Philippine Australian Medical Association (PAMA) has treated about 1,500 patients each year, Filipino and non-Filipino, since the 1990s.

Migrants have also become cultural workers and scholars. In the US, they have written their own memoirs as a cultural contribution to document the contributions Filipinos have made to the US in over 100 years of migration. The Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS) also opened its own museum in Stockton, California, in 2014. These stories dismantle negative stereotypes and offer a new narrative of will, hope, and positive outcomes.

There are also paradigmatic cases in Europe: a Filipina migrant who came to France in 1994 went down in history as the first Filipina to take her employer to court for modern slavery and won her case. She became a trade unionist in the Confédération française démocratique du travail, where she continued her work to protect the rights of all foreign workers in France.

MISSIONARIES SENT BY GOD

On a more strictly religious level, one cannot forget that these migrants bring with them a heritage of faith, devotion and spirituality that can be extremely valuable for Catholic communities in the destination countries. They can be “unexpected vehicles and messengers of God’s grace,” a “precious channel through which God wants to enrich and revitalize our communities,” as the document Orientamenti sulla Pastorale Migratoria Interculturale (Orientations on Intercultural Migratory Pastoral Care) notes, of the Section for Migrants and Refugees in the Vatican’s Dicastery for the Service of Integral Human Development (24 March 2022), which calls for a “pastoral care of the whole,” which values belonging to different cultures and peoples, envisaging “intercultural and inter-ethnic or inter-ritual parishes.”

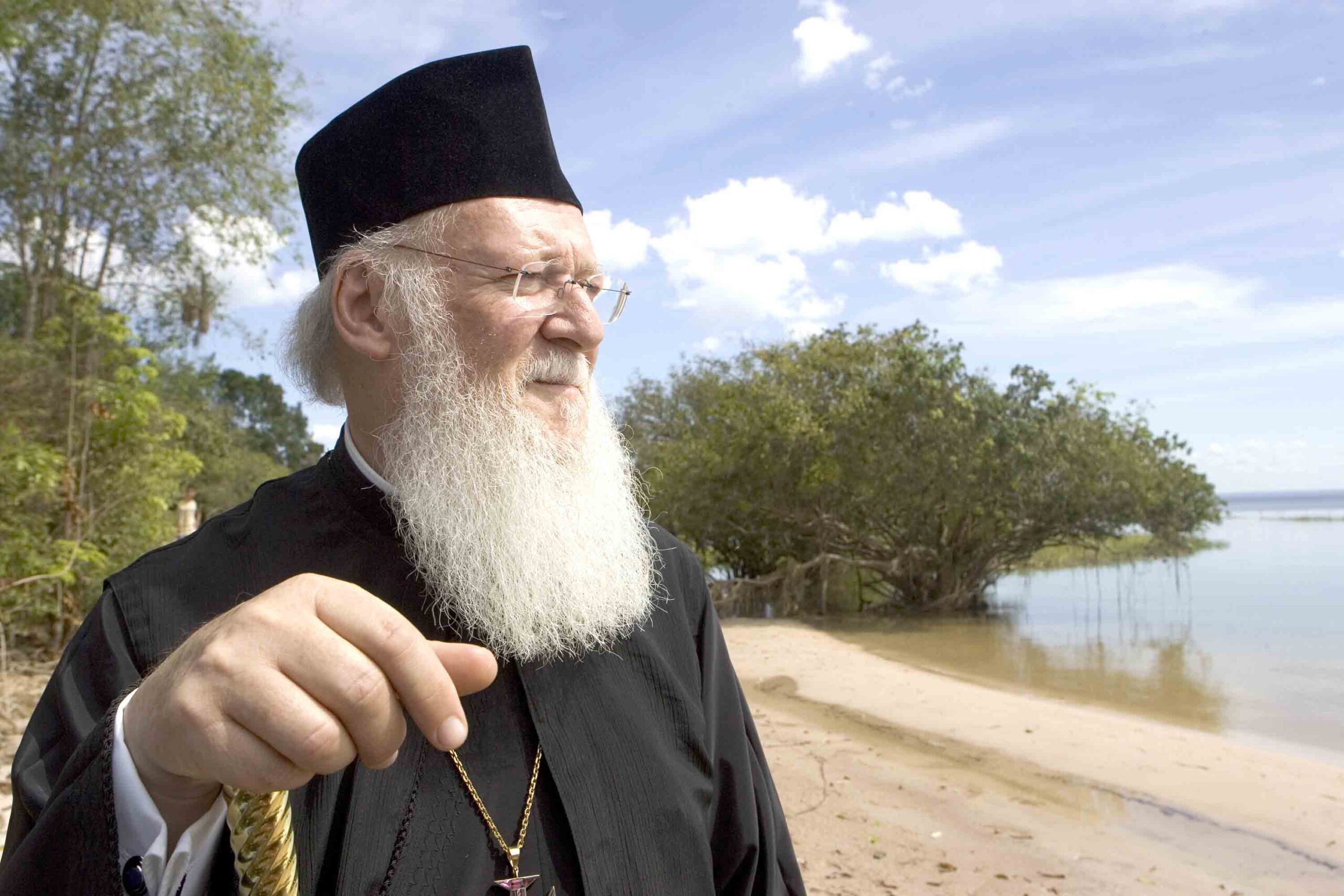

In Japan, for example, where alongside 450,000 Japanese faithful, there are just as many from abroad, especially Filipinos and Vietnamese, they “are missionaries sent by God, a great help to evangelization,” wrote the Church of Niigata. From the very beginning, a religious institute like the one founded by Blessed John Baptist Scalabrini saw emigration as “a providential instrument in God’s plan for spreading the Gospel.”

Migrants are “communities that evangelize,” wrote Fr. Sérgio O. Geremia, former Superior General of the Missionaries of St. Charles (Scalabrinians). The millions of Christians migrating from Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia and Africa to Europe, the United States, Canada and Australia are a wealth, in terms of faith, hope and charity, for the Churches of ancient tradition.

Against this backdrop, Philippine Cardinal Luis Antonio G. Tagle, speaking in October 2021 at the Study Seminar organized by the Pontifical Missionary Works (POM) to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the arrival of the Gospel in the Philippines (1521-2021), explained, “We received the gift of faith 500 years ago, but not only then: we still receive it from the Lord today. We received it and lived it as Filipinos, and we give it to the world as Filipinos, in our own peculiar way. In an archipelago of more than 7,500 islands, faith has spread from one island to another in a fruitful exchange. Today, many faithful Filipinos, even if they do not consider themselves missionaries or have not studied missiology, are missionaries in the family, at work, and in society; they pass on the faith with their lives. There are 10 million Filipino workers scattered all over the world. This migration movement has become a missionary movement. We are all missionaries sharing the gift of faith.” The diaspora of the faithful, then, becomes a paradigm for the Church’s evangelizing mission. Published in Agenzia Fides