I have come here not only because you are part of my city but also because you mirror the society out there. Your problems and sufferings remind me of the work I must do beyond these walls.”

This paragraph, taken from a talk given some years ago by the mayor of Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, when he visited the PDLs and distributed some gifts before Christmas, can introduce us to the reality of prisons.

Such words could have been said by any mayor here in the Philippines, who has taken to heart the conditions of those living behind bars and the lives of citizens in general, especially those who are more at risk of behaviors that may undermine individual and social life.

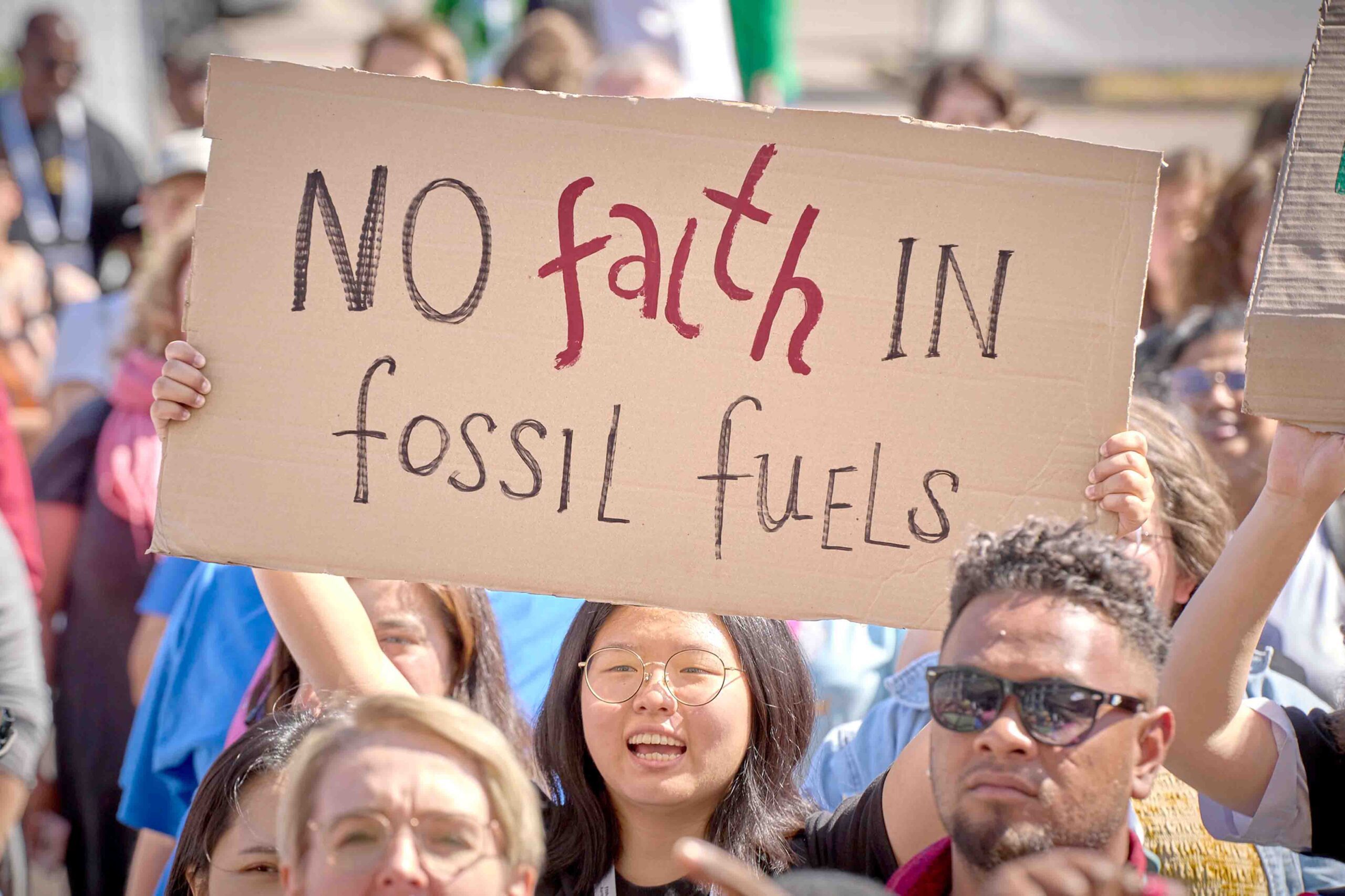

Behind every person who has committed a crime, whether an offender or someone who was unjustly accused and condemned, there is always something that went wrong in society, be it in the family or the local community, in the education system or the organization of the state, in prison structures, or in the global system in general.

Our encounters with the PDLs show us people of every walk of life, ethnicity, educational level, socioeconomic background, and religion; I have also noticed this at the New Bilibid Prison in Muntinlupa during these first months of my service.

For years, I have been trying to put into practice the advice of an old missionary who told me, “When you arrive in a country you don’t know and want to start understanding how society works, make sure to go first of all to a hospital, a court of law, a prison, and a cemetery.”

THE LEAST VISITED PLACE

Such places show us the value attributed to human life and dignity, whether it comes to being born or sick, when life is threatened or needs reformation, or when it comes to the memory of those who went before us. I dare say that of the four places mentioned above, the prison is probably the least visited, and this reminds us that it is not easy to put into practice Jesus’ words, “I was in prison, and you came to see me” (Matthew 25:36).

This difficulty becomes more evident when we are confronted by the highest level of love shown and demanded by the Lord, “Love your enemies.” Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a German theologian, offers an intermediate path towards such an ideal when he says, “The first form of love is listening, especially to the differences! The second is: do not despise the other!” Such words can be like a compass in our encounter with the PDLs.

However, there is another obstacle between us and those living behind bars. Let us consider a type of information that attracts many people: the crime news. One of the reasons why they are so popular is the fact that people become passionate about certain criminal plots and the minimal details of the story, and they share them with others to convince themselves, unconsciously, to be different and, above all, better than those ‘criminals’.

In such a case, our critical conscience could be reawakened to shake us once again through the words of Jesus, “The measure you give will be the measure you receive back” (Luke 6:38). It is important to consider the following verse when Jesus added, “Can a blind person lead another blind person? Surely both will fall into the ditch” (Luke 6:39).

If this is applied to the relationship with PDLs, it means that until people do not perceive and understand what makes them blind and deaf to what our brothers and sisters are undergoing while in prison, they will continue to guide others, through ideas, prejudices and choices, in a non-Christian direction and call for a punitive system of justice.

BREAKING THE SPIRAL OF VENGEANCE

Pope Francis, in his message for the World Day of Prayer for Peace 2020, even though he was addressing all Christians and people of good will, used words that fit our topic, “We should never encapsulate others in what they may have said or done, but value them for the promise that they embody. Only by choosing the path of respect can we break the spiral of vengeance and set out on the journey of hope” (n. 3).

Like in any modern state, in the Philippines as well, there are structures that aim at protecting both those who are ‘outside’ and those who committed a crime, and then use or propose various means for the reformation of those who are ‘inside’.

“To this end, the institution should utilize all the remedial, educational, moral, spiritual and other forces and forms of assistance which are appropriate and available, and should seek to apply them according to the individual treatment needs of the prisoners” (Bureau of Correction, Act 2013, Sec. 2, Par. 4).

The wide scope of such provisions reminds us that different people, from inside and outside the prison, can and are especially called to contribute to reforming those who are still tough, shut down, angry, and deeply wounded. Such a task is not easy.

It was not coincidental that one day a PDL told me in a rough way, “People praise doctors and nurses for treating and curing the sick, as they show dedication and courage, like during COVID-19. They praise teachers who promote the education of our young people. But then they ignore the guards and those who run a prison and have the heavy responsibility for reforming people who went astray.”

When we find the courage to approach someone who is suffering, in this case, the PDLs, even without saying or doing anything and offering our simple presence, although the other person may not want to change his or her situation or avoid or reject the truth, we change, and not rarely do we emerge strengthened by such experience.

FORGIVENESS

Indeed, we are confronted by a difficult reality that finds little space in the social debate, and it is often seen in open contradiction with the judicial process: forgiveness. A particular murderer, who underwent a profound change during his years in prison, shortly before his release, said, “If you slap someone and the other forgives you, then you understand the evil you have committed and feel defeated … But the greatest obstacle towards redemption is to feel nailed to the role of an evil man.”

Some time back, one of my companions, who was also working in the prison ministry, shared what had happened a few days before. “Last Sunday, I went to celebrate the Mass in the section of those condemned to death. One of the young PDLs, who was helping in arranging the altar, called me aside and then whispered to me, “’I am the one who killed one of your fellow missionaries, Fr. X. Do you forgive me?’ I was frozen for a short while, and then, with tremendous effort, I nodded. During the celebration, I was in shock and could not concentrate because I was asking myself whether my answer had been sincere. After the Mass, the man approached me again and asked, ‘If I prepare a letter for the family of Fr. X to ask forgiveness from them also; will you deliver it? ‘”

Suppose we accept to go beyond those physical and mental gates to overcome the prejudices that may ‘imprison’ us, most probably, we will realize that those forgotten untouchables of society are not ‘dangerous beasts’ to be avoided but rather people who are deeply wounded.

Whether they talk about it or refuse or pretend to be strong or acknowledge their weakness, they are often worried about their families. They think of the shame they brought upon them and the hardships they face because of them. They suffer boredom and loneliness as they spend years without a single visit when their relatives reject them, or they live on a distant island and have no money for the fare. They cry over the beloved wife who could not wait and got another man, over the children who cannot afford proper education, and over the old father who lives alone. Several cannot figure out how to restart life when they are free again or how to face the stigma of being an ‘ex-convict’.

Many PDLs already experience inner freedom thanks to their change; others are getting rid of some heavy burdens. Others are still angry about everything, with everyone and maybe with themselves as well. Others cannot find a point of reference for a new life. It is towards any of these that, as Christians, we feel called to offer a testimony of hope.

The author is a volunteer of the non-profit organization Philippine Jesuits Prison Service (PJPS) and offers sessions of counseling to the PDLs on a weekly basis.